by Philip Graham

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

During my college years, Donald and I had bonded over a love of literature and a shared ambition to become, some day, actual writers. While I chose the route of fiction, Donald wrote song lyrics, taking poetry classes to hone his craft.

The great songwriter love of his life was the Joni Mitchell of her first albums, Song to a Seagull, Clouds, and Ladies of the Canyon. But then Blue dropped, and it crushed Donald. He believed the new, conversational quality of Mitchell’s lyrics betrayed her past poetic strengths. While we sat in the college coffee shop he quoted a few lines from the song “California”:

So I bought me a ticket

I caught a plane to Spain

Went to a party down a red dirt road

and then protested with real hurt in his voice, “How could she write something so ordinary?”

I didn’t mind that Mitchell had moved away from her lyrical era of “mermaids live in colonies” and “sweet well water and pickling jars.” I thought she fully lived and breathed in her new songs, became more approachable as a fellow vulnerable human. Donald remained unmoved. I suggested that at least we still had her exquisite voice, her gift for melody, and her guitar playing—what haunted tunings!

He insisted he couldn’t listen to any song, no matter how beautiful, if he didn’t first respect the lyrics. I countered that no matter how well-composed a lyric, if the melody was a clunker I wouldn’t listen twice. The beauty of the music came first. If the words reflected that beauty? Bonus. Read more »

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

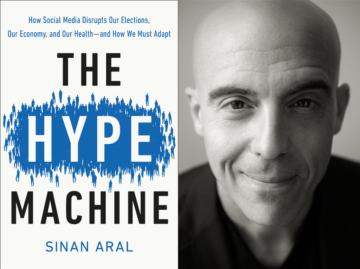

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success.

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success. Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

According to Donald Trump, in

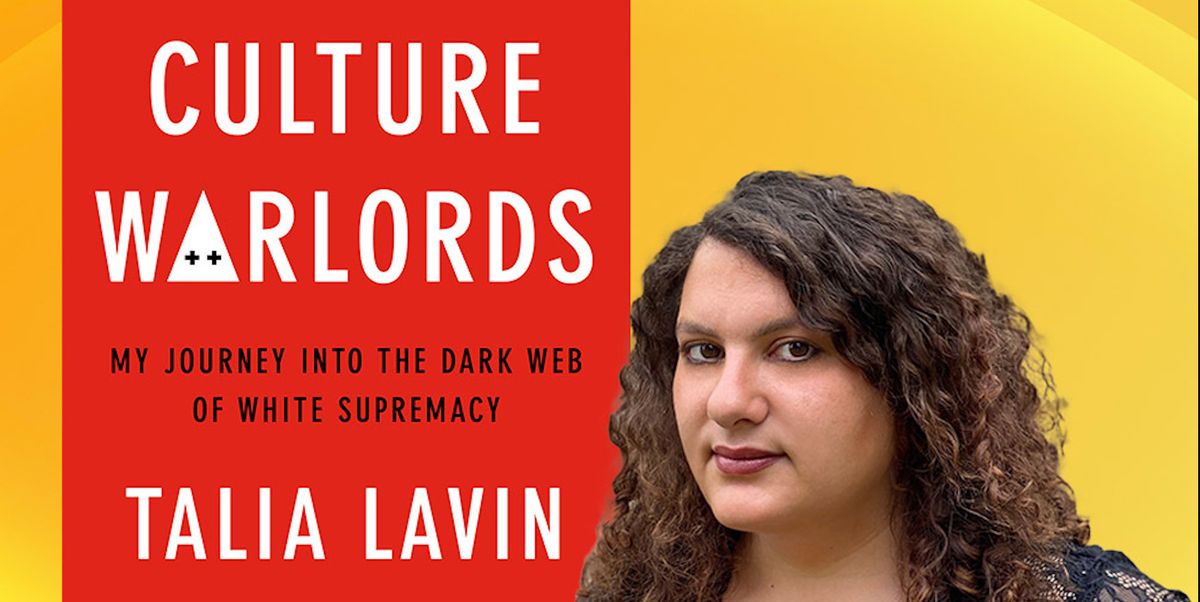

According to Donald Trump, in  Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend. Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t.

Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t. Many decades back when I was teaching at MIT, a senior colleague of mine, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a famous development economist, asked me at the beginning of our many long conversations what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”. A 2015 study by psychologist Jose Duarte and his co-authors found that 58 to 66 per cent of social scientists in the US are ‘liberal’ (an American word, which unlike in Europe or India, may often mean ‘left of center’), and only 5 to 8 per cent are conservative. If anything, social scientists in the rest of the world are on average probably somewhat to the left of their American counterparts. If that is the case, for the world in general social democracy is likely to be an important, though not always decisive, ingredient of their ideology. In European politics and intellectual circles there was a time when social democrats were considered the main enemy of the communists, at least in their rivalry to get the attention of working classes, but now with the fading away of old-style communists, social democrats have a larger tent, which includes some socialists of yesteryear as well as liberals, besieged as they both now are by right-wing populists.

Many decades back when I was teaching at MIT, a senior colleague of mine, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a famous development economist, asked me at the beginning of our many long conversations what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”. A 2015 study by psychologist Jose Duarte and his co-authors found that 58 to 66 per cent of social scientists in the US are ‘liberal’ (an American word, which unlike in Europe or India, may often mean ‘left of center’), and only 5 to 8 per cent are conservative. If anything, social scientists in the rest of the world are on average probably somewhat to the left of their American counterparts. If that is the case, for the world in general social democracy is likely to be an important, though not always decisive, ingredient of their ideology. In European politics and intellectual circles there was a time when social democrats were considered the main enemy of the communists, at least in their rivalry to get the attention of working classes, but now with the fading away of old-style communists, social democrats have a larger tent, which includes some socialists of yesteryear as well as liberals, besieged as they both now are by right-wing populists.

I’m disappointed in my columns so far. Not to say that they’ve been completely without value; I’ve managed to turn out some decent pieces and some kind readers have taken the time to tell me as much. But, taken together, my output exhibits a fault that I had sought to avoid from the outset. It has been far too occasional, too reactive, too of the moment in an extended, torturous moment of which I very much do not wish to be. There are exculpatory circumstances, of course. These are difficult times, and we are weak and vulnerable beings, and I am nothing if not an entrenched doom-scroller with a tendency for global anxiety. This is not an apology, because a core tenet of my approach to writing is a complete disregard for my audience. You’re all lovely people, I’m sure, but in order to write I have to provisionally discount your existence. This is, rather, a confession to the only person whose opinion matters to me as a writer. And that would be myself.

I’m disappointed in my columns so far. Not to say that they’ve been completely without value; I’ve managed to turn out some decent pieces and some kind readers have taken the time to tell me as much. But, taken together, my output exhibits a fault that I had sought to avoid from the outset. It has been far too occasional, too reactive, too of the moment in an extended, torturous moment of which I very much do not wish to be. There are exculpatory circumstances, of course. These are difficult times, and we are weak and vulnerable beings, and I am nothing if not an entrenched doom-scroller with a tendency for global anxiety. This is not an apology, because a core tenet of my approach to writing is a complete disregard for my audience. You’re all lovely people, I’m sure, but in order to write I have to provisionally discount your existence. This is, rather, a confession to the only person whose opinion matters to me as a writer. And that would be myself.