by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

You’ve been an on-again, off-again working band for a decade. During that period there have been numerous breakups and seemingly endless lineup changes. Then, after years of grinding and uncertainty, you finally hit it big in 1975. You earned it.

You’ve been an on-again, off-again working band for a decade. During that period there have been numerous breakups and seemingly endless lineup changes. Then, after years of grinding and uncertainty, you finally hit it big in 1975. You earned it.

But you’re also riding a larger cultural wave; you’ve been assigned to a niche, what people are now calling Southern Rock, a sub-genre that your band pre-dates.

So be it. You worked your ass off, and now you’ve arrived. You get signed to a major label. Your eponymous debut album goes gold. You have a single that does okay. You have a nickname; the frequently shuffling roster somehow ended up with a trio of guitarists, and you’ve been dubbed the “Florida Guitar Army.” And you have an opus. The last song on your new album is worthy of your genre predecessors, the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd. A confident, snarling intro is followed a fierce torrent of wailing guitar solos. Over nine minutes of kick ass, balls to the wall rock n roll, “Green Grass and High Tides Forever” will cement your place in Southern Rock lore.

Then it all starts to wobble.

You have trouble writing even passable hits for successive albums. In 1977, the Southern Rock patrons who helped get you signed to a major label, Lynyrd Skynyrd, go down in a plane crash. The Allmans have broken up. Corporate America’s starting to milk the redneck thing dry as Hollywood spews forth crap like The Dukes of Hazzard, a sure sign that this fad’s entering its pop culture death throes. Has Southern Rock run its course? Increasingly it feels like you have nowhere to turn, and now you find yourself in . . . New Jersey.

If there’s a moment in life that runs into the dizzying three-way intersection of what you’ve always wanted, what you can no longer stomach, and what you’re desperate not to lose, this performance embodies it.

How did I end up here?

Well, actually, you worked very hard to get here.

Yes, but how did I get here? How did my dream, which I hustled my ass off to achieve, turn me into its own punch line? And how can I get back to where I just was, approaching the peak and thinking the skies were limitless? Because it sure seems that if I back up in that direction, I’ll just tumble down and windup in the same place I fought so hard to get away from to begin with.

Some people think of life as a straight line that goes from beginning to end. But it’s not. Maybe it’s a circle containing cycles within cycles. Maybe it’s a twisting, turning maze whose walls are lined with fun house mirrors. Maybe life is a circuitous road to nowhere, all the scenery is warped, and you are not whom you think you are.

Maybe it’s an inspired nine minute song turning into a twenty-three minute orgy of excess because you’re afraid to abandon what got you here, but don’t like where it might be leading, and can’t figure out anywhere else to go. So you just keep running in place, worried you might be pointed in the wrong direction, but leery of what happens if you stop. Something that was once sublime and beautiful has become a gilded cage. And the only thing you want more than to escape it is to not return to whatever’s on the other side of these golden bars.

Yup. That’s life, more or less.

“Don’t be afraid!” That’s what all the TV life coaches, self-help authors, and inspirational posters tell you. Easy for them to say. They’re not strung out in northern New Jersey, between gigs at a convention center in Niagra Falls and a gymnasium in Oswego, NY. They’re not in the homestretch a 38-city tour that included playing a water park in Cleves, OH and a field house in Erie, PA before it concludes Jacksonville, the same city that produced none other than Lynyrd Skynyrd, in whose martyred shadow you shall forever reside. Those upbeat gurus and cheerleaders don’t have to face down the possibility that while you might return as conquering heroes this time around, champions beneath the hometown banner, you can also sense the diminishing returns and worry that the day is coming when you won’t be able to get back out again.

So here you stand. On the stage of the Capitol Theatre in Passaic, NJ for the second time this year. It’s the only place you’ve played more than once in 1978. The déjà-vu before the reckoning. What was new has aged; what was once old is reborn.

Maybe it all does come full circle. Or maybe you’ve just been here before.

That’s how I felt as I stared at my computer screen and watched The Outlaws stretch “Green Grass and High Tides Forever” into something that indeed seemed like forever as they played Capitol Theatre in 1978, because I too had been there before. That very venue is where I saw my first real concert.

In 1984, I was a few short blocks away, leaning against a parked car and taking a healthy slug from the large Coke bottle half-filled with rum that my friends were passing around. I was 16 years old and should’ve been a little cold in my denim jacket on a starless autumn evening, but I was too fired up from alcohol, caffeine, and adrenaline to notice.

A half-dozen of us had crammed into my friend Danny’s father’s car and crossed the Hudson River from the Bronx. We had tickets to something called Guitar Greats, and we were getting souped up before walking over to the Capitol to watch the show.

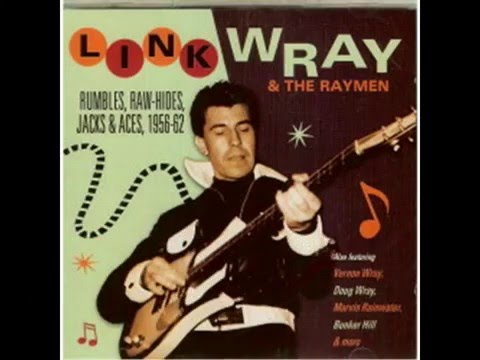

Guitar Greats was an all star collection of rock guitarists spanning a couple of generations. A few of them were wise old men, great players who were short on recent hits but long on respect and admiration: Steve Cropper from Booker T and the MGs, and Link Wray, who wrote the seminal early rock guitar instrumental “Rumble.” There were also a couple of guitarists who made their name by harkening back to earlier eras: blues/rock player Johnny Winter and rockabilly revivalist Brian Setzer. Most of the roster, however, consisted of 1970s rockers now a bit adrift, pickers from famous bands that were either recently kaput or on their way out: David Gilmour of Pink Floyd; Dickey Betts of the  Allman Brothers; Neil Schon of Journey. Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommie shared the stage with his fiancé Lita Ford, herself a former guitarist for the alarmingly young girl-group The Runaways, and who was now coming into her own as a metal head. British singer songwriter Dave Edmunds was the MC.

Allman Brothers; Neil Schon of Journey. Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommie shared the stage with his fiancé Lita Ford, herself a former guitarist for the alarmingly young girl-group The Runaways, and who was now coming into her own as a metal head. British singer songwriter Dave Edmunds was the MC.

Guitar Greats had the potential to be amazing. In reality, it was a bit of a mess. Each guitarist played two or three songs with a backing band. What that translated into was about fifteen minutes of music followed by about fifteen minutes of tedium as the stage crew got gear ready for the next artist. Rinse, spit, repeat. Just as you started to really get into it, you were left to sit around on your thumb.

All in all, it was a mixed experience. As best I can remember, I loved seeing and hearing Betts and Cropper. Unfortunately, none of us had any idea who the hell Link Wray was and, much to our eternal shame, we mocked him for being old and boring. I quietly enjoyed Neil Schon; I was a big Journey fan in high school, but this was Ronald Reagan’s dumb, macho America, and most white guys who liked rock considered them to be a fag band. Schon got booed as he took the stage, and didn’t do himself any favors with the decidedly analog crowd by having a very digital sound. But the cat can play.

We left during the encore, a group rendition of “Johnny B. Goode” that was disappointingly sloppy, but what do you expect when nearly a dozen electric guitarists play at the same time? We made our way to the car, piled in, and headed back to the Bronx. My lifetime of live music had just begun on the same stage where six years earlier, almost to the day, the Outlaws spun round in circles, seeking immortality and settling for endlessness.

For me, the Capitol Theatre was just the beginning. And as for The Outlaws? They soldiered on, cycling through various lineup changes, recording albums that sold fewer copies, and clinging to the road, playing ever smaller gigs. By 1996, their famed six-man lineup had repeatedly morphed beyond recognition; no less than thirty-nine different musicians had played in the band since 1967. The only permanent member was guitarist/singer Hughie Thomasson, the guy who wrote, sang, and played one of the two leads on “Green Grass.” That year he finally scuttled the band after landing a gig as a replacement guitarist for the reconstituted Lynyrd Skynyrd, back from the ashes of their plane crash. A decade after that, Thomasson left Skyknyrd, reformed The Outlaws, and brought back three members from its heyday, two others having earlier died from a drug overdose and suicide.

Hughie Thomasson rode it for two more years before passing away in his sleep from a heart attack in 2007. He was 55 years old. And the band kept going. A studio album in 2012, more tours, and live albums in 2015 and 2016.

Because unlike life, the show goes on.

Now watch the wheels come off the Southern Rock wagon in November, 1978 as The Outlaws spend nearly half an hour playing “Green Grass and High Tides Forever” to a frazzled audience in Passaic. Behold the wreckage of an already quite long song transforming into a flabby 23 minute jam, a rambling mess of a live version that I found to be both haunting and reassuring all at once.

Highlights

-Playful Intro

-The vaguely Chinese shirt that one guitarist is wearing

-These guys can actually play

-Jim Beam, road food, cheap beer, and the nagging question of How the fuck did I yet again end up in New Jersey, combine to create an inspired brand of lethargy

-The crowd: two chicks up front clapping their hands; one dude unashamedly playing air guitar; another wearing a cowboy hat and jumping up and down frantically

-Better than the neo-emo music that kid you work with is into

-When they finish, I think the bass player actually says “Thank you! Good night! Cleveland. Maybe.”

Lowlights

-That bandanna can’t hide your male pattern balding

-Disengaged talk-singing

-Leather pants

-Shit, did they just start over again?

-Profuse perspiration from cocaine and hot stage lights

-Aaaand, we’re done. Nope. Here’s a drum solo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hIaS_vYIQ_A

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com. It takes far less than 23 minutes to get through.