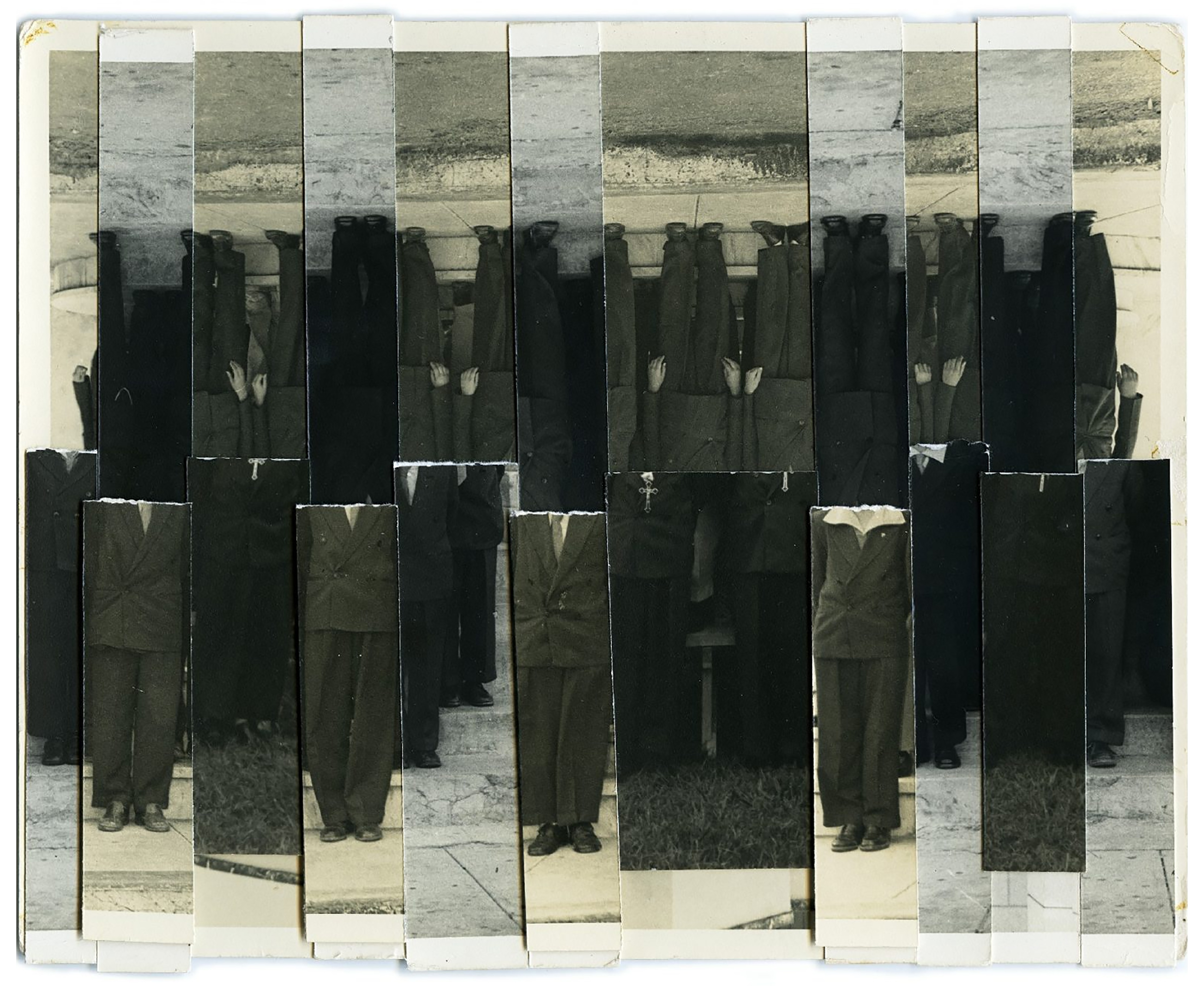

Ricardo Miguel Hernandez. From the series When The Memory Turns to Dust.

Hernandez’s work was on view at Isolo17 Gallery in Verona, Italy.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Joan Harvey

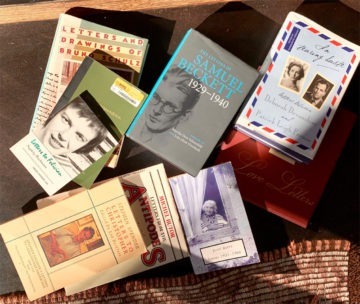

Ariana Reines and Terry Tempest Williams, writers one would never expect to be buddies, but who bonded at Harvard Divinity School, are having a public Zoom discussion in order to sell books. It’s a lovely, friendly discussion, but I’m shocked, shocked to hear that they send each other AUDIO letters. Audio letters? When they are so good at writing? When they have the chance to write to each other? Though, okay, why not? Henry James famously dictated his novels. Reines is amazingly articulate talking off the top of her head. Still, how is the pleasure the same? Williams does mention loving to actually write letters, so perhaps I shouldn’t judge.

Ariana Reines and Terry Tempest Williams, writers one would never expect to be buddies, but who bonded at Harvard Divinity School, are having a public Zoom discussion in order to sell books. It’s a lovely, friendly discussion, but I’m shocked, shocked to hear that they send each other AUDIO letters. Audio letters? When they are so good at writing? When they have the chance to write to each other? Though, okay, why not? Henry James famously dictated his novels. Reines is amazingly articulate talking off the top of her head. Still, how is the pleasure the same? Williams does mention loving to actually write letters, so perhaps I shouldn’t judge.

I think it extraordinary that letters are called letters, the name of that small denomination with which we build our words.

Mary Ruefle (in a lecture on letters that she first wrote, then spoke, and finally published in written form).

Of course there exist letters that talk of letters:

Many thanks for both letters, which arrived two days running, a tremendous treat for Kalamata, a town nobody writes to. I think people are subconsciously repelled by the letter K. It’s the reverse of the letter X, which always goes to people’s heads. Perhaps if sex were spelt seks or segs there wouldn’t be half so much fuss about it: nothing very glamorous about seks kittens or seksual intercourse but write ‘sex killer slays six’ and you’re in business.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, to his former mistress, Ricki Huston. So probably he was thinking of sex (or seks).

Most writers like to write letters. Or used to. Possibly not today. I too have been lured by texting’s immediacy. But for many of us older folks, there is still something seductive about addressing a particular person and sensibility on the other end whom you try to entertain and yet remain yourself as often as possible, and doing this at some length. And then, of course, the pleasure of getting something different but similar in return. Reciprocity. Response. There is also something enticing about the way you can put everything in, including the kitchen sink, and the clog in it, and the dog, and okay, maybe the Trogs. As well as the wind and the snow, and the election, and wish you were here. You can even complain about your bills and your health, as long as your complaining doesn’t have a demand. Read more »

by N. Gabriel Martin

When I was younger, I gravitated to conservatism’s deference to the actual. In my suspicion towards the progressive preference for ideas over what just is, it took me a long time to understand that conservatism misunderstands the future and therefore what it is attempting to achieve. Conservatism’s purported ambition to preserve the present and its roots in tradition are also efforts to bring about a different future, and therefore to change the world to suit its designs. However, it took me a long time to understand this self-contradiction at its heart.

In college I had a running argument with my friend Sky about Damien Hirst, the artist most famous at the time for suspending a great white shark in a tank of formaldehyde. Hirst was never my favourite artist (I actually like him more now than I did then), but I defended him because Sky’s dismissal appalled me. In my youth I embraced the culture as if it were a stately home I’d been welcomed into. While I was not uncritical, for me criticism had to come from a well of reverence for what was already there. It was the sanctity of established culture, tradition, and history that made criticising it worthwhile, and so criticism could never undermine that sacredness. Sky, however, criticised Hirst because she preferred a culture without him and what he was doing to it. I never understood that in my twenties, because I couldn’t understand the future.

At that time, the only way to respond to the world that made sense to me was to accept it and affirm it as it was, and comment on it as a passionate, but disinterested, observer. It wasn’t just that I revered tradition, I was also sceptical towards what I saw as the arrogance of progressivism; that it wants to improve upon things and believes it can. Read more »

by Peter Wells

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

My father was lifted out of the conservative background of his family by several years of residential higher education, had a job which caused us to move every three or four years, and wired the house to broadcast BBC Radio 4 (or its predecessor, the Home Service) to every room. My infant toys included female as well as male dolls, and, what’s more, one of the females was a little black girl! (Don’t be condescending – we’re talking the late 40s!) The first black person I met was an African student on homestay with us, who shed light for me on the mysteries of Latin grammar (I returned the compliment by teaching Latin to Zimbabweans five years later!). (Sorry! I meant well!)

So I pass Goodhart’s worldview test: “This [sc. Anywhereism] is a worldview for more or less successful individuals [Check, though rather less than more!] who also care about society [Check]. It places a high value on autonomy, mobility and novelty [Check] and a much lower value on group identity, tradition and national social contracts (faith, flag and family) [Check]. Most Anywheres are comfortable with immigration, European integration and the spread of human rights legislation [Check]. They … see themselves as citizens of the world [Check 110%!].”

The privileges opened up to me by this certification were immense. Repeatedly during my career I was able to enter the ‘alien’ environments of foreign countries, in Africa, Asia and the Middle East – not as a tourist but as a resident, worker, colleague, neighbour and friend. Seeing how people of a different culture live, think, laugh, learn, befriend, commute, pay, greet, and grieve, enabled me to put my own attitudes and presuppositions into perspective. I realised that what had looked to me like a central and obvious norm was just the point of view that I happened to have been brought up with. My wife and I were offered a glimpse of at least five very distinctive ways to live, instead of the sole option that most people are granted. More than anything else, this is what makes working abroad a joy and delight. The elusive quality of a national culture defies stereotyping. Like the flavour of a loved one’s cooking, it is itself. Africans, Arabs, Japanese are not reducible to epithets: they are what they are. A spouse who has had the same experience will know what you mean when you say, “That’s just like Oman / Malawi / Japan, isn’t it.” Our friends have no idea what we are talking about! You can, of course, obtain a similar experience by visiting a different part of your own country, or even someone else’s house, but for the full culture shock you need to change countries! Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Thomas O’Dwyer

A British government decision to build a road tunnel near the prehistoric site of Stonehenge in the south of England has stirred up a hornets’ nest of protest, certain to grow louder and noisier when construction work begins. Archaeologists and environmentalists are among those leading the growing resistance to the 3-km Stonehenge road tunnel. Public sentiment against any attempt by governments or commercial interests to threaten heritage sites can be visceral and powerful. Some people claimed in online posts to have felt physically ill when they heard reports that the Islamic State (ISIS) intended to destroy the magnificent ruins of Palmyra in Syria. Each year before the pandemic, over one million tourists visited Stonehenge to see the huge rock formations erected by Neolithic builders around 5000 years ago. The ring of standing stones, each 4 metres high, 2 metres wide, and weighing 25 tonnes, is the centrepiece of the unique historic site but it also stands in a complex of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments that include several hundred burial mounds.

That is why Druids, environmentalists and archaeologists have greeted the decision with anger and dismay. They predict that protesters will arrive from around the world to denounce the project. Remarkably, a minor local story about a road project in an obscure English county is making its way into headlines around the globe. This demonstrates that the British government is not the only one that must tread warily when it attempts to lay a grubby commercial hand on treasured items of national heritage. Public opinion may be fickle on many topics yet it seems universally united on the need to protect global cultural heritage – and this passion attracts curious attention from experts as diverse as psychoanalysts, sociologists, philosophers, and authors. Read more »

by Tamuira Reid

Hold your tongue. When the voice on the phone tells you how much they all loved her. That her smile could light up a room. The only time you ever saw her smile was the day after your sixteenth birthday, when you left your childhood home to leave your childhood behind. The house on the hill, surrounded by citrus trees and dry, cracking oaks. The house where as a boy you grew, despite little to no maintenance, not unlike the tress themselves. The house with a defunct stepfather, too miserable to know he was miserable, and a half-sister who begged you not to go. Who held out her palms, full of pennies from her piggy bank, I’ll give you all my money if you stay. Her hair was white-blonde and looked like an atom bomb cloud when the sun hit it from behind. You loved her as much as you could love anyone, which wasn’t much. Your heart had stopped working years before. Your heart had closed shop.

You remember giving that little girl a short, shitty hug that you wish could have been better. You remember a hummingbird vibrating in the air. You remember whispering into the space between your dead but alive bodies, don’t let her ruin you, too.

Hold your tongue. Don’t tell the voice on the phone how the smile on your mother’s ghastly face the day you left said it all. She had finally driven you out by cutting you off – from her love, from her touch, from the sound of her voice – a calculated, exacting erasure of the son she didn’t want in the first place. The one she tried to stop from growing inside her teenaged belly by drinking bleach and smoking peyote down at the river with her boyfriend, your father, egging her on. More, he’d say. Drink more. But the harder she tried to drive you out of her body, the harder you fought to stay. Until now. Read more »

by Charlie Huenemann

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica (1564). Dee was an English mathematician, court astrologer, diplomat, and spy. He was also a wizard, or at least an aspirant to wizardry. Like many European intellectuals of the 16th century, Dee devoted himself to what we identify today as esoteric studies, which means an interdisciplinary effort to discern a primordial truth through the study of ancient texts, alchemy, astrology, philosophy, theology, and magical practices. Ancient texts such as the Corpus Hermeticum and the Emerald Tablet promised a brand of wisdom that had made the ancient ages more powerful and knowledgeable than any age since, and their introduction into western Europe during the Renaissance gave scholars a hope of recovering ancient wisdom and restoring human nature to the perfection it had once enjoyed in the Garden of Eden, before – well, that part of the story you probably know already.

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica (1564). Dee was an English mathematician, court astrologer, diplomat, and spy. He was also a wizard, or at least an aspirant to wizardry. Like many European intellectuals of the 16th century, Dee devoted himself to what we identify today as esoteric studies, which means an interdisciplinary effort to discern a primordial truth through the study of ancient texts, alchemy, astrology, philosophy, theology, and magical practices. Ancient texts such as the Corpus Hermeticum and the Emerald Tablet promised a brand of wisdom that had made the ancient ages more powerful and knowledgeable than any age since, and their introduction into western Europe during the Renaissance gave scholars a hope of recovering ancient wisdom and restoring human nature to the perfection it had once enjoyed in the Garden of Eden, before – well, that part of the story you probably know already.

Dee wrote the Monas Hieroglyphica in just twelve days, under divine inspiration. The central idea is that the creation of symbols is at the same time a revelation of the primal forces of creation. Begin with a point. Extend the point so as to form a line. Fix one end and rotate the other to create a circle. You have just, in a sense, duplicated the creation of the Sun. Follow Dee’s instructions further – well, try to, for it soon gets pretty confusing – and before long you will have created a very potent symbol. Read more »

by Philip Graham

Michele Morano’s first collection of essays, Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, is a classic of travel literature that I have taught several times, to the great pleasure of over a decade’s worth of students. Now she has bested the power of that excellent book with a new collection of essays, Like Love. This book too, in a way, is a travel book, but one that stays close to home as Morano discovers and examines in her life the surprisingly varied terrains of affection, infatuation, love and devotion. And in this travel, Morano embraces the side paths that require uncommon honesty and self-examination that often go unspoken or unwritten. Readers following Michele Morano on this journey will be rewarded with their own moments of revelation, which may breathe life into memories perhaps long neglected.

Michele Morano’s first collection of essays, Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, is a classic of travel literature that I have taught several times, to the great pleasure of over a decade’s worth of students. Now she has bested the power of that excellent book with a new collection of essays, Like Love. This book too, in a way, is a travel book, but one that stays close to home as Morano discovers and examines in her life the surprisingly varied terrains of affection, infatuation, love and devotion. And in this travel, Morano embraces the side paths that require uncommon honesty and self-examination that often go unspoken or unwritten. Readers following Michele Morano on this journey will be rewarded with their own moments of revelation, which may breathe life into memories perhaps long neglected.

Philip Graham: I have long been an admirer of your writing, but your new book of nonfiction, Like Love, has taken my appreciation to new heights. Right from the start, the title tells a reader something special is afoot. Such a seemingly simple pairing of two single-syllable words, and yet, placed together, they resonate with many possible readings that only deepen as one proceeds through the book. What is the history of this title, was it an early, middle or late inspiration as you were writing the collection?

Michele Morano: Thank you, Philip, I appreciate your asking about the new book’s title, which came somewhat early in the process. I’d published a third of the essays as stand-alone pieces before recognizing the theme of odd romances, relationships that don’t follow the usual storylines, in my work—and in my life. I decided to make a book, and because I’ve always loved the title of Lorrie Moore’s short story collection, Like Life, I took inspiration from it for the title essay and the book as a whole. Like Love refers to all the unconsummated, shimmering infatuations, entanglements, relationships, and taboo attractions that happen throughout our lives. Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

As Thanksgiving approaches, we think about those things in our life for which we are thankful. I’m thankful for our healthcare system, and I’m doubly thankful for the opportunity to contribute to it.

I practiced hematology and oncology for over 30 years, diagnosing and treating blood disorders and cancer. During this time I wrote a little book, “Ask an Oncologist: Honest Answers to Your Cancer Questions,” and I put up a Facebook page with the same name to help promote it. Though I hadn’t planned to take questions, I shouldn’t have been surprised that questions began to come, given the title of the page.

At first, I avoided answering questions because I didn’t want to give out free medical advice as I was wary of liability and lawsuits. Then I got this:

You are truly a coat of many colors. Just wanted to thank you again for giving me my life back. It’s been 2 1/2 years cancer free. Truly a miracle when I read the transcripts from all the reports and tests from the past 3 years. Glad you’re doing well. Hope you have continued happiness. No questions. Just letting you know you are thought of often. —From one of your patients, a colorectal and liver cancer survivor

I was touched! This post made me see how much more a doctor provides than just treatment recommendations. And how much I missed seeing patients since retirement in 2017. Read more »

by Rafiq Kathwari

If you go to Kashmir today this is what you will see. As you drive away from Srinagar’s Hum Hama airport, a large green billboard with white lettering proclaims, Welcome to Paradise.

If you go to Kashmir today this is what you will see. As you drive away from Srinagar’s Hum Hama airport, a large green billboard with white lettering proclaims, Welcome to Paradise.

You will whip your head from side to side absorbing the sights and sounds of heaven: men in khaki in single file, machine guns slung over their shoulders. This will not seem odd, for you have heard about armed men in khaki necessary to secure paradise where they are called—what else‑—Paratroopers. This was once a paradox, but the paradigm is prescriptive.

Honk, honk, beep, beep, the shrill blowing of horns are the first sounds you will hear as you become aware that there are no traffic laws in paradise. Wow! No rules, only a few bearded men in blue, displaying PP insignia on their shoulders, clenching long bamboo sticks, idling indifferently at roundabouts as pardesis —what else would you call those who live in paradise— rush on, everyone including your driver wants to be on the fast track, all at once. You cannot but marvel at the paradisiacal confusion that follows. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election.

Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election.

And let’s be honest: Biden’s electoral college victory was frighteningly close. He won Pennsylvania by 0.7%, Wisconsin by 0.4%,a and Georgia by 0.3%. Had fewer than 0.5 % of Biden voters gone for Trump in these three states, he would have been re-elected. Moreover, in each of these states the votes received by the Libertarian candidate was greater than Biden’s margin of victory. Who knows how things might have gone had there been no Libertarian candidate.

And let’s keep being honest. But for the covid pandemic, Trump would quite likely have won. Indeed, had he been a more intelligent populist demagogue he might have raised his popularity prior to the election by embracing the role of national champion leading the fight against the virus.

So, like millions of others, after breathing a few sighs of relief and drinking a few celebratory toasts, I find myself asking: How is it possible? Why did over 70 million people vote for a man who to so many of us appears quite obviously to be a pathologically self-centered con man who is callously indifferent to the well-being of others, and who spews an almost continuous stream of barefaced and often quite absurd lies. And I charitably forbear from mentioning his ignorance, his incompetence, his laziness, his bigotry, his sexism, his bullying, his corrupt dealings… Read more »

by Lawrence Blume and Raji Jayaraman

The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has declared that “The moment has come for our nation to deal with systemic racism…” The wide span of policy remedies it goes on to propose reflects the breadth of the problem. A further challenge is that systemic racism runs deep, operating not only at the level of interpersonal interactions but from the workings of our social systems. It may be sustained by formal structures such laws or rules, in which case an obvious remedy is to reform those structures. But it can equally be sustained by amorphous structures that are harder to combat.

The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has declared that “The moment has come for our nation to deal with systemic racism…” The wide span of policy remedies it goes on to propose reflects the breadth of the problem. A further challenge is that systemic racism runs deep, operating not only at the level of interpersonal interactions but from the workings of our social systems. It may be sustained by formal structures such laws or rules, in which case an obvious remedy is to reform those structures. But it can equally be sustained by amorphous structures that are harder to combat.

One of the most insidious mechanisms through which systemic racism can be sustained is the vicious circle of self-fulfilling beliefs. Here is the idea. Suppose there are two groups, Blacks and Whites. Blacks hold beliefs about Whites, and Whites hold beliefs about Blacks. They interact with each other, choosing behaviours based on their beliefs. Everybody’s beliefs are validated by the behaviours they see.

We say that these beliefs are “in equilibrium” because each group’s belief enables the other. The representation each group holds about the other is correct because and only because each group holds these representations. When a large number of individuals in a market or some other social structure interact—and this is where the “systemic” part of racism enters—the beliefs turn into a self-fulfilling prophesy. Positive, “pro-social”, behaviours in this context are sustained by positive beliefs, resulting in a virtuous circle. Negative, “anti-social”, behaviours are sustained by negative beliefs, resulting in a vicious circle.

In his brilliant book, An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal saw racial disparities in the United States in precisely this light. “White prejudice and discrimination”, he writes, “keep the Negro low in standards of living, health, education, manners and morals. This, in its turn, gives support to White prejudice. White prejudice and Negro standards thus mutually ‘cause’ each other.” While Myrdal implicated deliberate discrimination in this process, subsequent work by Kenneth Arrow and others has taught us that the vicious circle operating in systems with no deliberate prejudice, can still generate discriminatory outcomes.

How does this happen? Read more »

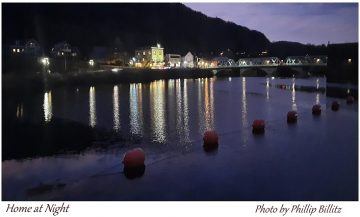

our town rests in a mountain-bowl

at twilight, common and small

as dust and dream but huge in life

beyond what it seems, its few lights jitter

on the river’s skin,

the dam pond’s spillway

lets its waters out as

upstream they come in

under a steel truss bridge,

the dam buoys’ stillness

under street-light drapes

upon a river’s surface

with a hue of grapes

as a ridgeline drops

like the backs of snakes

until it meets a flow

without grudge

or hates

Jim Culleny

11/14/20

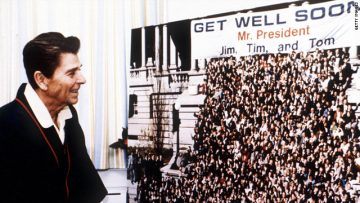

by Godfrey Onime

Just months after the new president was sworn into office, a would-be assassin’s bullet whizzed through the air and sliced into his chest. It cracked his rib, punctured his left lung, and barely missed his heart. It was March 30th, 1981 and Ronald Reagan was rushed to the George Washington University Hospital, in Washington, DC. His wife arrived as Reagan was being whisked to surgery and the injured president managed to croak, “Honey, I forgot to duck.” Reagan recovered fully after surgery, becoming the first U.S. president to survive an assassination attempt after a gunshot. Three years later and aged 73, he would clinch a resounding reelection to become, until now, the oldest person to win a presidential bid. But soon questions of a potential mental decline began to mount concerning the septuagenarian, such as when during a 1984 general election debate he told an anecdote that meandered aimlessly and fizzled to nowhere. A decade later, Reagan would announce that he had Alzheimer’s disease.

Age, it is often said, is just a number. But when it comes to the presidency of the United States, is it really? Should it simply be? This question is compounded by the lack of guidance in the U.S. constitution: While it places a minimal age requirement of 35 to run for office, it imposes no upper age limit.

And now, the country has elected Joe Biden to assume the presidency at age 78 – one year older than when Reagan, after a second term, left the post. That is among the many presidential histories that Biden’s election has made — the oldest person to date to be rewarded with America’s highest office. Yet, an advanced age puts a person at increased risk for diseases and health complications, including heart attack, stroke, various cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, and of course, death. After all, as George Burns once quipped, “At my age, flowers scare me.” Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

I’ve been reading Stanley Corngold’s surprisingly interesting Walter Kaufmann: Philosopher, Humanist, Heretic. I say “surprisingly interesting” because I only thought of Kaufmann as the author of a dated book on Nietzsche and a number of anthologies on Nietzsche and other existentialist figures.

As it turns out, Kaufmann was a fascinating figure in his own right. Born in Germany in 1921, Kaufmann was raised Lutheran, but, finding that he couldn’t accept the doctrine of the Trinity, Kaufmann converted to Judaism – after the Nazis had already assumed power! – only to find that both his paternal and maternal parents had converted to Lutheranism from Judaism.

Kaufmann spent one year studying for the rabbinate in Berlin before fleeing Nazi German for the United States. Alone in a new country, Kaufmann taught himself English, enrolled at Williams College and then received an M.A. in philosophy at Harvard before joining the U.S. Army in Military Intelligence and returning to Germany, where he served as an interrogator, before returning to complete his Ph.D. in philosophy at Harvard. He then embarked on a 30-year teaching career at Princeton.

Apparently, for all of the stability of his academic career, Kaufmann remained a peripatetic figure. Before his untimely death in 1980 at the age of 59, Kaufmann had already traveled around the world – four times!

Reading Corngold’s chapter on the book that cemented Kaufmann’s reputation, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, I was struck by the ways in which Kaufmann’s own biography must have predestined him to be receptive to Nietzsche’s philosophy. Read more »

by Robyn Repko Waller

As the fall term winds down for universities across the US (and abroad), what has one semester, interrupted, and another one, planned, under COVID taught us about university life?

In March 2020, with the growing community spread of COVID-19 upon the nation, universities shuttered in response to the seismic early rumblings of the pandemic. Starting on the West Coast, institutions such as University of Washington and Stanford closed their campuses, suspending in-person teaching and activities, a trend that would quickly reach institutions of higher learning across the nation all the way to the eastern shores of the US.

Empty lecture halls and dormitories — at least in term time — are a rarity. Lecture halls, laboratories, and dormitories of universities are meant to ring and echo with the hustle and bustle of human interaction. Gilbert Ryle, in his well-known explication of ‘category mistake’ in The Concept of the Mind gave this imagined (mis)description of the University:

A foreigner visiting Oxford or Cambridge for the first time is shown a number of colleges, libraries, playing fields, museums, scientific departments and administrative offices. He then asks ‘But where is the University? I have seen the where the members of the Colleges live, where the Registrar works, where the scientists experiment and the rest. But I have not yet seen the University in which reside and work the members of your University.’

Ryle’s aim was to illustrate that if one thinks, as the hypothetical visitor does, of the University as another member of the class of items which contains these buildings and locales, one has misunderstood what kind of thing the University is. One has seen the University already. But, I want to suggest, the COVID pandemic teaches us that neither the visitor nor Ryle even is entirely correct about the nature of the University. Visit the deserted campus structures and quad, vacated in response to COVID, and one has not really seen the University. Rather, the University is constituted by its human constituents, past and present — the academic community.

But where is the University — the academic community — now? And what is the academic community now? Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

Consider the lobster. Rigidly separated from the environment by its shell, the lobster’s world is cleanly divided into ‘self’ and ‘other’, ‘subject’ and ‘object’. One may suspect that it can’t help but conceive of itself as separated from the world, looking at it through its bulbous eyes, probing it with antennae. The outside world impinges on its carapace, like waves breaking against the shore, leaving it to experience only the echo within.

Its signature move is grasping. With its pincers, it is perfectly equipped to take hold of the objects of the world, engage with them, manipulate them, take them apart. Hence, the world must appear to it as a series of discrete, well-separated individual elements—among which is that special object, its body, housing the nuclear ‘I’ within. The lobster embodies the primal scientific impulse of cracking open the world to see what it is made of, that has found its greatest expression in modern-day particle colliders. Consequently, its thought (we may imagine) must be supremely analytical—analysis in the original sense being nothing but the resolution of complex entities into simple constituents.

The lobster, then, is the epitome of the Cartesian, detached, rational self: an island of subjectivity among the waves, engaging with the outside by means of grasping, manipulating, taking apart—analyzing, and perhaps synthesizing the analyzed into new concepts, new creations. It is forever separated from the things themselves, only subject to their effects as they intrude upon its unyielding boundary. Read more »