by Godfrey Onime

Ponder this. It is the 15th century and you have a high chance of contracting and dying from a rampant infection. Turns out that you could intentionally infect yourself with a small dose of the contagion, get slightly sick, and become protected for life. Of course, things are not always that simple. You could get more than just a little sick. You could even die, but 1000 times less likely than if you acquired the infection naturally. Would you infect yourself and beloved family members? I believe I would, and I’ll tell you why.

Long before science knew about bacteria and viruses or that they caused diseases, long before vaccines were even imagined, that exactly was the dilemma that people the world over faced — whether or not to preemptively infect themselves, in hopes of preventing more serious illnesses, or worse, death. Indeed, those were desperate times, with no antibiotics, hospitals, or ICUs.

One vexing affliction for this historical palaver was smallpox, which was rampart in much of recorded history. Not only was it highly infectious, it rendered its victims extremely sick: raging fevers, splinting headaches, searing backaches, crippling fatigue, monstrous skin eruptions, and quite often, death. When it did not quickly and gruesomely kill sufferers, the scourge left them disfigured, not the least with unsightly pockmarks on the face. Little wonder then that many started to intentionally infect themselves and kids with smaller and possibly weaker doses of the infection, which they obtained from the oozing sores on the skins of the afflicted. This practice of using the actual, live bug to self-induce infection is called variolation. Among those intentionally exposed to smallpox through variolation, about 1-2 in 100 may die. For those who got the infection naturally, about 30 in 100 died. Read more »

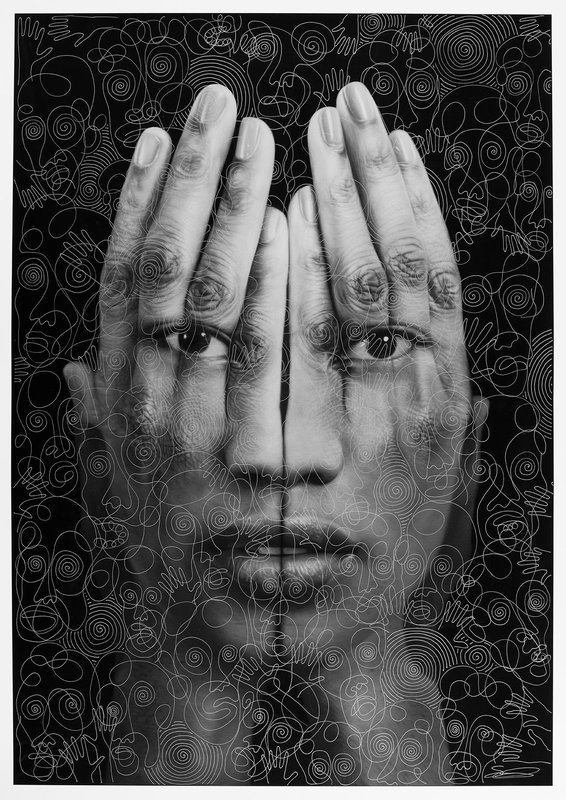

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

The violent, insurrectionist attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 was due, in part, to the success of the Nation’s system of public education, not its failure. Since Ronald Reagan announced in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem,” federal authorities have worked to dismantle and erase any vestiges of democratic education from our system of public education. Free-market values replaced democratic ones. Public education slowly but consistently was transformed by neoliberal ideologues on both sides of the aisle into an institution both in crisis and the cause of the Nation’s perceived economic slip on the global stage. Following Reagan’s lead, all federally sponsored school reform efforts hollowed out public education’s essential role in a democracy and focused instead on its role within a free-market economy. In terms of both a fix and focus, neoliberalism was and remains the ideological engine that drives the evolution of public education in the United States. These reform efforts have been incredibly successful in reducing public education to a general system of job training, higher education prep, and ideological indoctrination (i.e., American Exceptionalism). As a consequence of this success, many of the Nation’s citizens have little to no knowledge or skills relating to the essential demands of democratic life. The culmination of the neoliberal assault on democratic education over the last forty-years helped create the conditions that led to the rise of Trump, the development of Trumpism, and the murderous, failed attempt at a coup d’etat in Washington, DC. From what I have read, I am not confident that your plans for public education will address these issues.

The violent, insurrectionist attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 was due, in part, to the success of the Nation’s system of public education, not its failure. Since Ronald Reagan announced in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem,” federal authorities have worked to dismantle and erase any vestiges of democratic education from our system of public education. Free-market values replaced democratic ones. Public education slowly but consistently was transformed by neoliberal ideologues on both sides of the aisle into an institution both in crisis and the cause of the Nation’s perceived economic slip on the global stage. Following Reagan’s lead, all federally sponsored school reform efforts hollowed out public education’s essential role in a democracy and focused instead on its role within a free-market economy. In terms of both a fix and focus, neoliberalism was and remains the ideological engine that drives the evolution of public education in the United States. These reform efforts have been incredibly successful in reducing public education to a general system of job training, higher education prep, and ideological indoctrination (i.e., American Exceptionalism). As a consequence of this success, many of the Nation’s citizens have little to no knowledge or skills relating to the essential demands of democratic life. The culmination of the neoliberal assault on democratic education over the last forty-years helped create the conditions that led to the rise of Trump, the development of Trumpism, and the murderous, failed attempt at a coup d’etat in Washington, DC. From what I have read, I am not confident that your plans for public education will address these issues.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions. Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at  Arma virusque cano: Sing,

Arma virusque cano: Sing, This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.

This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.  In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”