Lina Zeldovich in Nautilus:

One day in 2010, when oncologist Paul Muizelaar operated on a patient with glioblastoma—a brain tumor infamous for its deathly toll—he did something shocking. First, he cut the skull open and carved out as much of the tumor as he could. But before he replaced the piece of skull to close the wound, he soaked it in a solution containing Enterobacter aerogenes,1 bacteria found in feces. For the next month, the patient lay in a coma in an intensive care unit battling the bacteria he was infected with—and then one day a scan of his brain no longer showed the distinctive signature of glioblastoma. Instead, it showed an abscess, which, given the situation, Muizelaar deemed a positive development. “A brain abscess can be treated, a glioblastoma cannot,” he later told the New Yorker. Trying it, he thought, was worth the chance. He had done this only as a means of last resort in a couple of hopeless cases—but ultimately, his patients still passed away, which led to a scandal that forced him to retire.

One day in 2010, when oncologist Paul Muizelaar operated on a patient with glioblastoma—a brain tumor infamous for its deathly toll—he did something shocking. First, he cut the skull open and carved out as much of the tumor as he could. But before he replaced the piece of skull to close the wound, he soaked it in a solution containing Enterobacter aerogenes,1 bacteria found in feces. For the next month, the patient lay in a coma in an intensive care unit battling the bacteria he was infected with—and then one day a scan of his brain no longer showed the distinctive signature of glioblastoma. Instead, it showed an abscess, which, given the situation, Muizelaar deemed a positive development. “A brain abscess can be treated, a glioblastoma cannot,” he later told the New Yorker. Trying it, he thought, was worth the chance. He had done this only as a means of last resort in a couple of hopeless cases—but ultimately, his patients still passed away, which led to a scandal that forced him to retire.

Muizelaar’s approach may sound beyond outrageous, but it wasn’t entirely crazy. For over 200 years medics have known that infections, particularly those accompanied by fevers, can have a strange and shocking effect on cancers: Sometimes they wipe the tumors out. The empirical evidence for these hard-to-believe cures has been documented in medical literature, dating back to the 1700s. In the 19th century, some doctors tried treating cancer patients by deliberately infecting them with live bacterial pathogens. Sometimes it worked, sometimes the patients died. Injecting people with dead bacteria worked better and, in fact, saved lives, at least in some cancers. The problem was that it didn’t work consistently and repeatedly so it never became an established treatment paradigm. Moreover, no one could explain how the method worked and what it did. Doctors speculated that infections somehow revved up the body’s defenses, but even in the early 20th century, they had no means of elucidating the mysterious force that devoured the tumor.

More here.

“I’m a storyteller” is a common self-description for virtually everyone in the film industry these days, from directors and scenarists to publicists and marketers. The phrase is a quintessential humble-brag. It carries a sense of modesty: “I may have a profoundly intricate knowledge of my craft, but at heart I’m no different from the people spinning a good yarn for their kids.” But it also holds a whiff of epic continuity, placing the speaker in a line that reaches back to Homer, and beyond that to the nameless bards who first narrativized our species into civilization. All to say: the phrase has passed through ubiquity to become an increasingly mocked cliché. Which is why it was so refreshing to hear the French director Leos Carax say in a recent interview with the

“I’m a storyteller” is a common self-description for virtually everyone in the film industry these days, from directors and scenarists to publicists and marketers. The phrase is a quintessential humble-brag. It carries a sense of modesty: “I may have a profoundly intricate knowledge of my craft, but at heart I’m no different from the people spinning a good yarn for their kids.” But it also holds a whiff of epic continuity, placing the speaker in a line that reaches back to Homer, and beyond that to the nameless bards who first narrativized our species into civilization. All to say: the phrase has passed through ubiquity to become an increasingly mocked cliché. Which is why it was so refreshing to hear the French director Leos Carax say in a recent interview with the  However reductive it may be to call the painter Bob Thompson the Jean-Michel Basquiat of the 1960s, the comparison is inescapable.

However reductive it may be to call the painter Bob Thompson the Jean-Michel Basquiat of the 1960s, the comparison is inescapable.

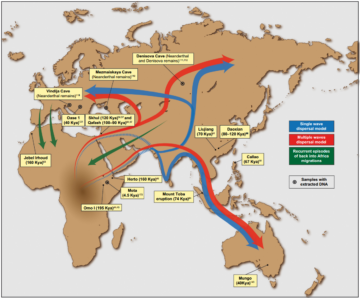

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.