by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle.

I was amazed how well-informed people were about who was doing what in which department in the country, who was pushing the (research) boundary where, which young faculty you had to attract before others grab them, what was the going market rate for a particular ‘hot-shot’ scholar, who was having an offer from which top department, and so on. (This reminds me of a phone conversation I had with the Dean of a top east-coast university much later when I joined Berkeley. This Dean wanted to know if I’d be interested in joining his University. Before he went any farther, I told him that I had only recently settled down in Berkeley, both my wife and myself liked the place, and just bought a house, and so I’d not be interested in moving. He talked for a while and then gave up. But before ending the conversation, I think he took pity on me and gave me a bit of ‘personal advice’. He said he could see that I was not yet used to the system in the American academic market. “When somebody offers you a job”, he said, “you don’t say ‘no’ even before I told you the salary I was going to offer you, which I am sure is much higher than what Berkeley is paying you. Even if you are ultimately not really interested, you try to get all the information, take the time, bargain with your Department, and get a raise for yourself”).

At the MIT Department those days the most revered leader clearly was Paul Samuelson, who every day at noon would preside over the lunch table at the Faculty Club in the top floor of the building. At the table, he’d often entertain us drawing upon his spectacular collection of stories and gossip, not just about economists, but often about physicists and mathematicians. To Paul there was a clear hierarchy of disciplines. It was visibly demonstrated to me one day when we took a visiting English friend who wanted to meet Paul. We told Paul that he’d be interested to know that this friend had done his degree in Astrophysics, but now he was thinking of moving to Economics. At this Paul immediately said, putting his hand above his head, “Astrophysics, then Economics (he lowered his hand to his chest level), what next? Theology? (moving his hand to the knee level). Read more »

The characters of

The characters of  Otto Celera 500L, it’s one that catches the eye. It looks like no other plane out there, and for a good reason: unique aerodynamics.

Otto Celera 500L, it’s one that catches the eye. It looks like no other plane out there, and for a good reason: unique aerodynamics. Isaiah Berlin understood the parable of the fox and the hedgehog – ‘the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’ – to illustrate two styles of thinking. Hedgehogs relate everything to a single vision, a universally applicable organising principle for understanding the world. Foxes, on the other hand, embrace many values and approaches rather than trying to fit everything into an all-encompassing singular vision.

Isaiah Berlin understood the parable of the fox and the hedgehog – ‘the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’ – to illustrate two styles of thinking. Hedgehogs relate everything to a single vision, a universally applicable organising principle for understanding the world. Foxes, on the other hand, embrace many values and approaches rather than trying to fit everything into an all-encompassing singular vision. What is it about Poe that grips the popular imagination so, like the medieval Iron Shroud shrinking inward and threatening to crush the narrator of

What is it about Poe that grips the popular imagination so, like the medieval Iron Shroud shrinking inward and threatening to crush the narrator of  Standing in the middle of a room previously inhabited by a now-absent figure can conjure an eerily potent atmosphere, traceable through sensations rather than words. Perhaps it’s because so much of what shapes the edges of any individual’s persona resides within the colors they prefer, their cooking and cleaning smells, or the sounds they regularly hear emanating from the pipes in their walls or a creak in their floorboards. When a person’s body exits their habitat, all the things that previously swirled in and around their tangible body remain, suspended in the air in a thick, viscous hum. These remnants permeate the objects the person leaves behind, too, charged with energy, appearing as sentient creatures rather than a lifeless pile of stuff.

Standing in the middle of a room previously inhabited by a now-absent figure can conjure an eerily potent atmosphere, traceable through sensations rather than words. Perhaps it’s because so much of what shapes the edges of any individual’s persona resides within the colors they prefer, their cooking and cleaning smells, or the sounds they regularly hear emanating from the pipes in their walls or a creak in their floorboards. When a person’s body exits their habitat, all the things that previously swirled in and around their tangible body remain, suspended in the air in a thick, viscous hum. These remnants permeate the objects the person leaves behind, too, charged with energy, appearing as sentient creatures rather than a lifeless pile of stuff. Moments of sociopolitical tumult have a way of generating all-encompassing explanatory histories. These chronicles either indulge a sense of decline or applaud our advances. The appetite for such stories seems indiscriminate—tales of deterioration and tales of improvement are frequently consumed by the same people. Two of Bill Gates’s favorite soup-to-nuts books of the past decade, for example, are Steven Pinker’s “

Moments of sociopolitical tumult have a way of generating all-encompassing explanatory histories. These chronicles either indulge a sense of decline or applaud our advances. The appetite for such stories seems indiscriminate—tales of deterioration and tales of improvement are frequently consumed by the same people. Two of Bill Gates’s favorite soup-to-nuts books of the past decade, for example, are Steven Pinker’s “ T

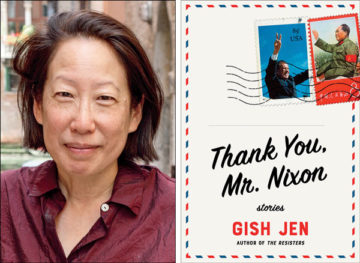

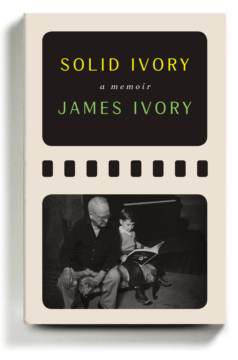

T Merchant and Ivory, normally working with the writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, were one of the most dominant cinematic forces of the late 20th century, rolling out luxuriously appointed adaptations of E.M. Forster and Henry James novels, with the occasional more contemporary anomaly like Tama Janowitz’s “Slaves of New York.” Merchant died in 2005; Jhabvala in 2013. After decades conjuring the Anglo-American aristocracy clinking cups in gardens and drawing rooms, Ivory, the survivor, is ready to spill the tea.

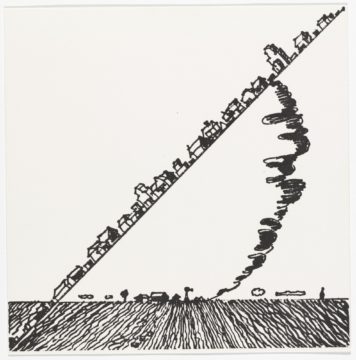

Merchant and Ivory, normally working with the writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, were one of the most dominant cinematic forces of the late 20th century, rolling out luxuriously appointed adaptations of E.M. Forster and Henry James novels, with the occasional more contemporary anomaly like Tama Janowitz’s “Slaves of New York.” Merchant died in 2005; Jhabvala in 2013. After decades conjuring the Anglo-American aristocracy clinking cups in gardens and drawing rooms, Ivory, the survivor, is ready to spill the tea. Benjamin Braun and Adrienne Buller also in Phenomenal World (image: Joëlle Tuerlinckx,

Benjamin Braun and Adrienne Buller also in Phenomenal World (image: Joëlle Tuerlinckx,  Ajay Singh Chaudhary in The Baffler (image

Ajay Singh Chaudhary in The Baffler (image  Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World: Something unnatural

Something unnatural