by Michael Liss

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

I wrote that, last month, in “The Coupist’s Cookbook,” and was challenged in an email by a friendly but dubious reader.

Is there a common history, a type of universal “origin story”? Does that make for a compact, of the type the signers of the Declaration of Independence acknowledged, when they pledged their “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor”? If so, aren’t we the heirs to that bundle of benefits and burdens? Finally, to explore further the implication of my correspondent’s email, if that “deal” no longer applies, how do we coexist and maintain a government in which we can freely express ourselves and choose, and change, our leaders?

I don’t have easy answers. I’ve written roughly a dozen pieces for 3Q in the last few years about Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Lincoln, and FDR. Although those great men have to have believed in it, and I believe in it, I don’t know that it’s at all communicable or even comprehensible to someone of a different age, different political views, or different education. With no other place to look, I reached back to my parents’ generation, which seemed to do all these civic things so much better, and found something in, of all places, a song.

In 1939, the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal program with a mandate to fund live performances for an audience without much disposable income, and to provide jobs to a Depression-decimated artistic community, mounted a production of a new Broadway revue, Sing for Your Supper. The finale was a patriotic appeal in the form of a duet—“Ballade of Uncle Sam” (music by Earl Robinson, lyrics by John La Touche).

Sing for Your Supper ran for 60 performances, closing only when a timorous Congress, concerned about possible “infiltration” of the arts by Communists, cut off funding for the entire FTP program. Producer Norman Corwin then offered “Ballade of Uncle Sam” to CBS, which liked the sound and the sentiment. It had Robinson rearrange it as a solo and chorus piece, and renamed it “Ballad for Americans.” The legendary singer and actor Paul Robeson was hired to perform it.

“Ballad for Americans” had its first airing (live, of course, with the CBS Studio orchestra and chorus) on November 5, 1939. The impact was instantaneous and extraordinary. There are stories of the phones and phone switchboard operators at CBS being overwhelmed by callers. Enthusiasm was so great that they repeated the performance on New Year’s Eve. The public couldn’t get enough, so, in February 1940, Robeson and the American People’s Chorus recorded it (on 78s) for Victor Records, and, a few months later, Der Bingle himself (Bing Crosby, the most popular singer in America) cut his own version for Decca Records. Then, in one of the more ironic moments in American politics, it was played at two Presidential nominating conventions—Republican and Communist.

Why the popularity? What raised it from being a pleasant, niche ditty that you might see performed at a high school graduation, to a phenomenon? Some of it can surely be ascribed to the times. The Germans had invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and then, on May 10, 1940, began a march through much of Western Europe with incredible (and menacing) speed. In the Far East, Japan had been flexing its muscles continuously in China and Manchuria since the early 1930s. Conflict with the United States seemed inevitable. Finally, at home, a strong strain of isolationism tied FDR’s hands, while economic recovery sputtered. By 1940, American GDP had barely recovered to December 1929 levels. Optimism was difficult.

“Ballad For Americans” filled a space in people, gave them a sense of belonging, linked them to the heroic past, and told them they could be part of the future. Even now, dated though it clearly is, it retains a certain potency. Take 10 (or 20) minutes away from whatever political distractions you engage in and listen to it. I’ve included links to both the Robeson and Crosby versions; both use nearly identical lyrics (later performers would often include contemporary references), and both run almost exactly 10 minutes. The difference is in shading and delivery, but both carry a message of pride and hope.

Bing’s is the smoother of the two, a bit more lushly arranged and orchestrated, and includes Crosby’s vocal tricks like his croon/warble and his deft way of sliding into the sound of others. It’s also a little more emotionally light, closer to Crosby’s public image of accessibility. His voice softens some of the tougher portions, taking the sting out of phrases that might otherwise draw fire. If there’s a weak spot, it’s in the accompanying Ken Darby Singers—they almost sound too professional, too bright. Still, it’s an admirable presentation and even a little bold for Crosby, given some of the content.

The Robeson version is the one I grew up with, the one I sang to with my parents and sister. The recording quality isn’t quite as good; you can hear the technical limitations, particularly with the brass. That quickly becomes irrelevant when you are presented with the immense power of Robeson’s vocal presence. His bass-baritone, placed more in a call-and-response setting than Bing’s, and with a chorus that sounds a little more real-person, creates a dialog that builds relentlessly in both volume and emotional depth. If the opening seems a little hokey to you, be patient with it and put aside your cynicism. Robeson and the chorus have their own story to tell, and one of the bits of magic they manage to pull off is to sing it as if they were speaking from personal experience.

I prefer the Robeson recording, with his insistent, pile-driver of a voice, but both Robeson and Crosby put the message over beautifully. Look at some of the Robeson/Crosby lyrics and you can see that the basic premise is simple: An unnamed stranger appears to a crowd, and they all have what amounts to a conversation about themselves and their pasts. There are predominant themes that are distinctly American virtues: First, we are not an aristocracy, our history is made by people both great and modest, so our efforts are communal, and our victories communal. Second, we succeed despite having to climb a mountain of skepticism (“Nobody who was anybody believed it, Ev’rybody who was anybody, they doubted it.”). Third, our goals have civic and political virtue—independence and what it brings (“We hold these truths to be self-evident, That all men are created equal.”). Further, we self-correct—we don’t just free the slave, we recognize injustice (“Man in white skin can never be free, While his black brother is in slavery.”) And we grow, we always push forward—the pioneers, the Gold Rush, expansion West, railroads, giant cities, taking on big challenges in war and peace. For all that, for every challenge met, there are still naysayers, yet we still persevere and seek our own path (“And they are doubting still, And I guess they always will, But who cares what they say, When I am on my way”).

It’s a potent set of images, and the crowd comes together, connects. But, who is the stranger? Where does he come from? What does he do? He tells them he does everything, every type of job: “Engineer, musician, street cleaner, carpenter, teacher…” He’s the everybody who is nobody, the nobody who is everybody: “[T]he ‘etceteras’ and the ‘and so forths’ that do the work.” This strains credulity, so they call him on it: “Now hold on here, what are you trying to give us? Are you an American?” He’s an American. Not only does he do everything, he’s also of all races and religions and national backgrounds. He is them, and they are him. They are a community. So it should be, because he, and they, and America itself still have things to do. They will keep the faith, as “her greatest songs are still unsung.” And, as always, they will do it all together, and will overcome:

Solo: Out of the cheating, out of the shouting. Out of the murders and lynching

All: Out of the windbags, the patriotic spouting, Out of uncertainty and doubting, Out of the carpetbag and the brass spittoon, It will come again. Our marching song will come again!

It can be done because they possess a character that is “[d]eep as our valleys, High as our mountains, Strong as the people who made it.” The last question is resolved. The stranger, the crowd, and even the audience are all Americans, with a destiny of communal greatness. They need only choose it, and work for it.

I don’t know if this satisfies my reader, but, if we are to find our way back from this abyss we are in, there is going to have to be something in those ten minutes to still hold onto. For now, this is the best answer I can offer.

Epilogue: Bing Crosby was named Most Admired American in 1948, but “Ballad For Americans,” like Paul Robeson himself, eventually got caught in politics. He continued to speak (forcefully) for the cause of freedom at home and abroad, and campaigned on behalf of Henry Wallace and his Progressive Party in 1948. Opposition to him intensified in the later 1940s, causing the loss of local performance venues, and, in some places, “Ballad For Americans” became an unwanted stepchild, with scores in school districts tossed or ripped from larger songbooks. Robeson himself became a lightning rod for protests and violence. In August 1949, his potential headlining at a benefit concert for the Civil Right Congress in Peekskill, New York, led to a postponement after the audience was attacked with rocks and bottles by locals. A second concert, on September 4, 1949, that included Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, went off without incident, until it ended, and then both audience and performers had to run a gauntlet of protests along the road home. Up to 140 people were injured while law enforcement mostly stood by. In the 1950s, Robeson was blacklisted and his passport revoked, stilling, for a time, at least his artistic voice. It took most of the decade, and the Supreme Court’s 1958 ruling in Kent v. Dulles to see it restored. After that, Robeson mounted a comeback abroad, but time, and the pressure, had taken their toll on him, and he suffered a series of health crises. He lived roughly the last 15 years of his life in comparative seclusion, first with his wife Essie and then, after she passed, with his son, and then his sister, never performing in public again. He died January 23, 1976. In death, he was embraced in ways often denied him in life: an award from the United Nations General Assembly for his work on Apartheid, entrance into the College Football Hall of Fame (he had been an All-American at Rutgers), a Lifetime Grammy, and, a little improbably, in 2004, his face on a 37-cent stamp.

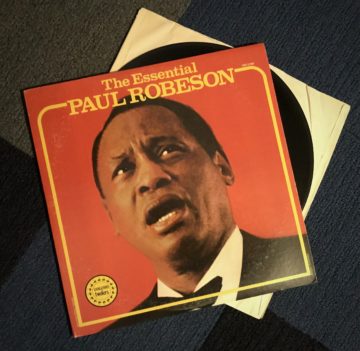

In The Essential Paul Robeson, there’s a track of him performing Othello’s final soliloquy. The first few lines seem somehow appropriate for this great and tragic personality.

Soft you; a word or two before you go. I have done the state some service, and they know’t. No more of that. I pray you, in your letters, When you shall these unlucky deeds relate, Speak of me as I am; nothing extenuate, Nor set down aught in malice: then must you speak, Of one that loved not wisely but too well.