by Bill Murray

Consider the medieval mariner, slighted and sequestered, hard-pressed and abused, gaunt, prey to the caprice of wind and wave, confined below decks on a sailing ship. If the captain doesn’t get the respect he demands, he will impose it. So will the sea.

Consider the medieval mariner, slighted and sequestered, hard-pressed and abused, gaunt, prey to the caprice of wind and wave, confined below decks on a sailing ship. If the captain doesn’t get the respect he demands, he will impose it. So will the sea.

The sailor found solace in ritual. You get the idea he rather enjoyed taboo things. If the ship’s bell rings of its own accord the ship is doomed. Flowers are for funerals, not welcome aboard ship. Don’t bring bananas on board, or you won’t catch any fish. Don’t set sail on Fridays (In Norse myth that was the day evil witches gathered).

Helge Ingstad, an explorer we are about to meet, wrote that “Norsemen firmly believed in terrible sea trolls …. And those who sailed far out on the high seas might be confronted with the greatest danger of all: they risked sailing over the edge of the world, only to plunge into the great abyss.”

If they fell short of the abyss, what did they find? Fortunate men like Eirik the Red found safe harbors and hospitable enough terrain in Greenland to scratch out a life beyond the reach of Norwegian kings. Freedom.

No men found untold riches. More likely came calamity, hardship, deprivation. Life on an ancient sailing ship was a slippery log over a raging torrent. Yet medieval sailors pressed on, and the boundary of the world pushed ever farther west.

Fifty years ago Helge Ingstad and his wife Anne-Stein discovered remnants of a settlement in Newfoundland they suspected was the site known from Viking sagas as Vinland. The state of radiocarbon dating art a half century ago suggested the settlement was active between 990 and 1050.

We already knew certain artifacts around the Vinland site were cut down by metallic tools. This suggested the woodsmen were European, since indigenous people were not known to have metal tools. Then three years ago scientists established the “globally coherent signature” of a sunstorm in 993 CE by comparing tree rings. They compared forty four samples from five continents. This sunstorm (of a magnitude that has happened only twice in 2000 years) caused a readily detectable radioactive “spike.”

Finally, last month scientists applied their new tree ring knowledge to some of those same samples, from fir and juniper trees. Some even retained their bark, making it easy for researchers to count tree rings from the 993 “spike” outward. They conclude that an exploratory Norse mission to L’anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, chopped down those trees in precisely 1021 CE.

•••••

Helge Marcus Ingstad’s big life spanned three centuries, 1899 to 2000. A wunderkind Norwegian lawyer at twenty-three, he chucked it all to live with an indigenous Canadian tribe for three years as a trapper, returned to Norway, became a governor in east Greenland, then governor of Svalbard, where he met his wife Anne-Stine.

For successive summers Helge and Anne-Stine sailed up and down Newfoundland’s west coast searching for evidence of Vinland. Year after year, it was mind-numbing, repetitive, wearying, wet work.

Everywhere they sailed they asked the same tired and practiced question. Did anyone know of any “strange, rectangular turf ridges?”

In the summer of 1960 the Ingstads called at a village on the northernmost tip of Newfoundland. They arrived by ship because there were no roads. Just thirteen families. And here, it turned out, someone did know of such ridges. On a sodden shoreline like endless others, they met George Decker, “the most prominent man in the village.”

Ingstad: “Decker took me west of the village to a beautiful place with lots of grass and a small creek and some mounds in the tall grass. It was very clear that this was a very, very old site. There were remains of sod walls. Fishermen assumed it was an old Indian site. But Indians didn’t use that kind of buildings, sod houses.”

The name of this windblown spot almost 400 miles north of St. John’s is L’Anse aux Meadows. Farley Mowat, the grand old man of Canadian adventure writing, calls this a distortion of the French L’Anse aux Méduses, or Jellyfish Bay.

The Ingstads spent that winter arranging an excavation to be led by Anne-Stine, by that time an archaeologist at the University of Oslo. It started the next summer and continued seven years.

Experts from Toronto and Trondheim collaborated to fix charcoal from the L’Anse blacksmith’s furnace, with the state of the tech at the time, as dating from 975 to 1020. The excavation revealed three stone and sod halls, five workshops, iron nails and decorative baubles consistent with the period. By 1961 they had authentic archaeological evidence that the Ingstads had found Vinland.

The team unearthed sod-and-timber halls built to sleep an entire expedition. The encampment lay tight against itself suggesting foreboding, a garrison mentality, uneasy disquiet in an alien land.

They built three halls between two bogs at the back of the beach near what they call today Black Duck Brook. Each had room for storage of turf, for what wood they found, for drying fish. A smaller area centered on an open-ended hut with a furnace for iron working, near a kiln to produce charcoal needed for ironworks.

Parks Canada has assembled replica buildings alongside the ruins, with detail down to spare blocks of peat for roof repair, turf squares stacked fifteen high like bags of potting soil on pallets at the garden center.

On a Wednesday in June, before summer has taken hold, smoke rises from a chimney in the main hall. There are four fireplaces the length of the building, fires for illumination and cooking, iron kettles for boiling stews.

The scent of wood smoke makes me eager to step inside, toward well-insulated, welcome warmth. You may shed your winter wear inside and you will be surprised how roomy is the interior space, much taller than a man.

An elaborate lattice weaves across the ceiling. The walls are extravagantly hung with ropes – coils and coils of line – a sailor’s colony. Against the back wall the length of the building run benches wide enough for sleeping, everything lined with skins.

It took twelve Parks Canada workers six months to craft that outdoor museum. Birgitta Linderoth Wallace, author of Westward Vikings, reckons that is comparable to sixty explorers working for two months of summer, or six weeks for ninety men. Surely these buildings were meant to withstand winter.

Maybe the Vinland voyages explored further south in summer. Maybe, as colder weather returned, so the men returned to L’Anse to winter, tell and embellish tales of their exploits and mainly, to stay warm. Excavations unearthed a soapstone spindle whorl that suggests spinning, possibly weaving. Perhaps the explorers brought bags of unspun wool, a worthwhile way to keep hands busy over the tedious winter.

•••••

In time the party encountered “skrælings,” local people unlike the Inuit they knew in Greenland. These were Native Americans, “short in height with threatening features and tangled hair on their heads.” The word skrælings is translated as “small people” by scholars, “screeching wretches” by the more flamboyant.

That first group of explorers, who built their settlement in tight formation, had been right to do so. The Greenlanders’ first encounter with other people did not go well.

One day the men came upon nine strangers sheltered under upside-down skin boats and the Norse killed all but one. The escapee returned next day primed for vengeance. The men saw countless canoes advancing from the sea, and the expedition’s leader, Thorvald Eiriksson, exclaimed: “We will put out the battle-skreen, and defend ourselves as well as we can.”

Battened down, the men withstood the skrælings’ attack unharmed except, calamitously, for Thorvald: As the skrælings fled he wailed, “I have gotten a wound under the arm, for an arrow fled between the edge of the ship and the shield, in under my arm, and here is the arrow, and it will prove a mortal wound to me.”

Thorvald Eiriksson became the first European buried in the New World and, dispirited, the Greenlanders soon departed for home. According to Linderoth Wallace, “the next expedition to Vinland is said to have been mounted for the explicit purpose of bringing his body back to Greenland.”

A clash on a subsequent expedition killed two more would be settlers. The Sagas tell us that the explorers realized “despite everything the land had to offer there, they would be under constant threat of attack from its prior inhabitants.” The Vinland settlement effort stalled.

Perhaps the explorers recognized all along they didn’t have the numbers for permanent colonization. Maybe the realistic among them never planned more than temporary missions to this continent-sized storehouse of supplies. Had they intended a sustained occupation there would have been a church and a cemetery, but there were none. The explorers never farmed the fields. Neither barn nor byre for cattle, no fold or corral for sheep.

Archaeologists found three butternuts, a tree never known to grow in Newfoundland, its range from southern Quebec to northern Arkansas. Their presence suggests the explorers traveled at least as far as New Brunswick, more than 400 miles to the southwest. Down there food may have grown wild, for “that unsown crops also abound … we have ascertained not from fabulous reports but from the trustworthy relations of the Danes,” wrote a German scribe in the 1070s.

Nowadays most everyone agrees the Vinland of the Sagas was a land and not a single, specific site like L’Anse aux Meadows. Vinland perhaps comprised an area from L’Anse along the Newfoundland coast south to Nova Scotia, down the St. Lawrence to present-day Quebec City where the river narrows, then up the opposite coast in a grand arc along Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Quebec and Labrador back to L’Anse.

•••••

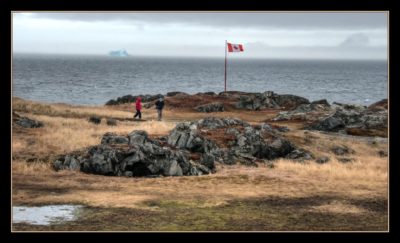

Today is as fine a day as we have seen in northern Newfoundland, no sun but no rain and a fresh, steady, penetrating wind. Hardscrabble ground, uneven, firm enough if you are deft, but step off the rocks and you will sink to your boot tops in the bog.

Helge Ingstad wrote of a Norse “will of iron and a character able to endure privation and pain without a murmur,” and he must surely be right. Standing out by Black Duck Brook dressed in snug twenty-first century down clothing, I can not summon to mind the impossible hardship of men dressed in skins and bad footwear who sailed from Greenland in the cold and the wet, dodging icebergs, serrating wind and jostling seas.

A foot bridge crosses the brook leading toward the ruins. We modest few visitors pick our way up and down the paths. The original shelters, slumped back to Earth, now present as mounds, the effect a gently dimpled plain. Plaques identify the dimples: Huts and halls, the boat shed, the forge, the carpentry shop, the smithy.

Twenty people make a ring around the Parks Canada man in ranger-wear, who is fit to the place, wild and outdoorsy maybe like a pirate. He spins tales with a performer’s twinkle; his audience is all in. Sometimes he must raise his voice if the wind kicks up, bearing down across the Gulf of St. Lawrence from Labrador.

But walk away, find your own place, stand still, and the sounds slide away. Trifling waves come to shore too far away to hear. The cinematic clash of icebergs proceeds in acoustic stealth, distant enough not to disturb the quiet. Seabirds’ calls soar away on the wind and we are left only with the benign rustling of the tall grass.

We stand by the brook. Helge Ingstad wrote in the 1960s, that “There is salmon in Black Duck Brook, we caught them with our bare hands.” George Decker’s grandfather told him there was considerable forest here in his younger days, but from the brook to the shoreline to Labrador this morning I am hard pressed to find a single tree.

The fog clears across the strait and Labrador emerges, brooding. Wisps of fog play up its cliff sides, snowy patches running up onshore. A peculiar lopsided iceberg, too heavy to bob, has shadowed us through the day.

In the course of an hour the fog recedes, pulling with it more character and definition from the icebergs, moving their surfaces from amorphous gray through bland white, in the end striking out toward the flamboyance of blue, even aqua.

The original European explorers stared hard into this view, wind burning their faces and blowing their beards as they ended their era of discovery one thousand years ago. Five hundred years before the European voyages that got all the good press, here at the end of their long road stood a mottled and murderous clan of northmen.

I imagine the view today is much as it was then. Expansive but spare, open to possibilities and full of challenge, but also full of promise. Two virgin continents awaiting the hand of European man. The original scruffy explorers left that promise for others to fulfill, but these rough-hewn men, standing here astride this earth wild and untamed, they had found the future.