Dwight Garner at the New York Times:

The future author of “Strangers on a Train,” the Ripley series and many other novels was learning to mediate between her intense appetite for work — few writers, these diaries make clear, had a stronger sense of vocation — and her need to lose herself in art, gin, music and warm bodies, most of them belonging to women.

The future author of “Strangers on a Train,” the Ripley series and many other novels was learning to mediate between her intense appetite for work — few writers, these diaries make clear, had a stronger sense of vocation — and her need to lose herself in art, gin, music and warm bodies, most of them belonging to women.

There are a lot of late-night taxi rides in these journals. And necking in restaurant bathrooms (a bonus for same-sex couples). And stealing kisses from married women. And running down to Chinatown to get tattoos. Highsmith’s first was her own initials in Greek lettering on her wrist, small, in green ink.

She was always half-broke. When you date women, she joked, there’s no man to grab the check. She liked to be out. If you are made nostalgic by the mention of defunct Manhattan bars and restaurants, this book will be like reading the liner notes to a Billie Holiday or Frank Sinatra album at midnight through a glass of bourbon.

more here.

I didn’t choose “Roadrunner” because its recording timeline and its image of a person literally circulating through the night allowed me to discuss these things. I chose it because it’s magic. I have felt its magic for a long time but never had a good story about it. And because I couldn’t figure out a path to a book about “Tell Me Something Good,” a song at least as magical. That book goes “Something something—wait! Did you know that Chaka Khan got the name ‘Chaka’ when she joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Chicago?” And I am not sure I know how to tell that story in a way that does justice to Chaka, and Rufus, and the BPPSD, and Chairman Fred. So there I was with “Roadrunner.” And once I set out along Route 128, there was no way for me not to situate it within what is for me the true metanarrative of the U.S. present: the catastrophic trajectory of capitalism.

I didn’t choose “Roadrunner” because its recording timeline and its image of a person literally circulating through the night allowed me to discuss these things. I chose it because it’s magic. I have felt its magic for a long time but never had a good story about it. And because I couldn’t figure out a path to a book about “Tell Me Something Good,” a song at least as magical. That book goes “Something something—wait! Did you know that Chaka Khan got the name ‘Chaka’ when she joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Chicago?” And I am not sure I know how to tell that story in a way that does justice to Chaka, and Rufus, and the BPPSD, and Chairman Fred. So there I was with “Roadrunner.” And once I set out along Route 128, there was no way for me not to situate it within what is for me the true metanarrative of the U.S. present: the catastrophic trajectory of capitalism. There’s an idea, particularly popular with some comedians, that the very point of comedy is to say the unsayable, to push boundaries and envelopes by articulating uncomfortable truths.

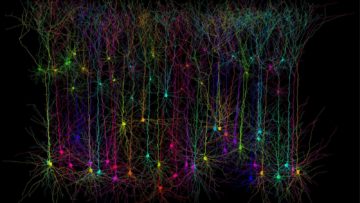

There’s an idea, particularly popular with some comedians, that the very point of comedy is to say the unsayable, to push boundaries and envelopes by articulating uncomfortable truths.  Imagine you are in a meadow picking flowers. You know that some flowers are safe, while others have a bee inside that will sting you. How would you react to this environment and, more importantly, how would your brain react? This is the scene in a virtual-reality environment used by researchers to understand the impact anxiety has on the brain and how brain regions interact with one another to shape behavior.

Imagine you are in a meadow picking flowers. You know that some flowers are safe, while others have a bee inside that will sting you. How would you react to this environment and, more importantly, how would your brain react? This is the scene in a virtual-reality environment used by researchers to understand the impact anxiety has on the brain and how brain regions interact with one another to shape behavior. The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz dubbed Dante “a patron saint of all poets in exile” and, as an exile himself for much of his life, likely could relate to both the Florentine’s proud defiance and his urge to seek some measure of solace in the constancy of the natural world. When, in 1960, Miłosz moved to the United States, accepting a teaching position at UC Berkeley, nature was very much on his mind. He was already living in exile, having defected to France nearly a decade earlier, but he had not escaped the haze of history that hung heavily over postwar Europe. The past was integral to Miłosz’s writing throughout his career, especially the horror he witnessed so viscerally in wartime Warsaw, but in order to continue to describe it “in such a manner that it is preserved in all its old tangle of good and evil, of despair and hope,” he had to soar above it, as he put it in 1980, after winning the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz dubbed Dante “a patron saint of all poets in exile” and, as an exile himself for much of his life, likely could relate to both the Florentine’s proud defiance and his urge to seek some measure of solace in the constancy of the natural world. When, in 1960, Miłosz moved to the United States, accepting a teaching position at UC Berkeley, nature was very much on his mind. He was already living in exile, having defected to France nearly a decade earlier, but he had not escaped the haze of history that hung heavily over postwar Europe. The past was integral to Miłosz’s writing throughout his career, especially the horror he witnessed so viscerally in wartime Warsaw, but in order to continue to describe it “in such a manner that it is preserved in all its old tangle of good and evil, of despair and hope,” he had to soar above it, as he put it in 1980, after winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. A mouse finds itself in a box it’s seen before; inside, its white walls are bright and clean. Then, a door opens. On the other side, a dark chamber awaits. The mouse should be afraid. Stepping into the shadows means certain shock — 50 hertz to the paws, a zap the animal was unfortunate enough to have experienced just the day before. But when the door slides open this time, there is no freezing, no added caution. The mouse walks right in.

A mouse finds itself in a box it’s seen before; inside, its white walls are bright and clean. Then, a door opens. On the other side, a dark chamber awaits. The mouse should be afraid. Stepping into the shadows means certain shock — 50 hertz to the paws, a zap the animal was unfortunate enough to have experienced just the day before. But when the door slides open this time, there is no freezing, no added caution. The mouse walks right in.

For over forty years, radical Islam has been one of the most clichéd expressions in Western political discourse. From around the time of the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, it has been invoked habitually by policymakers, the media and academics alike. At the heart of justifications for war, it has also dominated analysis of global terrorism and political violence since 9/11. Yet it has often displayed a ‘we know it when we see it’ quality, evident not only in assumptions that underpin its usage in the lexicon of Western security policies but in settled genealogies of ‘Islamism’ or ‘jihadism’ recycled routinely by scholars across various disciplines. Rather than being self-evident, however, analysis of radical Islam functions more as a kind of Rorschach test onto which assorted interpretations of ‘radicalism’ and ‘Islam’ are projected. In my article for RIS, I address the vagaries of radical Islam’s widespread presence in the Anglophone academy by treating the labelling of Islam and Muslim actors as radical as a particular scholarly practice.

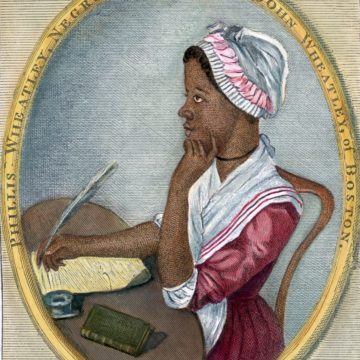

For over forty years, radical Islam has been one of the most clichéd expressions in Western political discourse. From around the time of the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, it has been invoked habitually by policymakers, the media and academics alike. At the heart of justifications for war, it has also dominated analysis of global terrorism and political violence since 9/11. Yet it has often displayed a ‘we know it when we see it’ quality, evident not only in assumptions that underpin its usage in the lexicon of Western security policies but in settled genealogies of ‘Islamism’ or ‘jihadism’ recycled routinely by scholars across various disciplines. Rather than being self-evident, however, analysis of radical Islam functions more as a kind of Rorschach test onto which assorted interpretations of ‘radicalism’ and ‘Islam’ are projected. In my article for RIS, I address the vagaries of radical Islam’s widespread presence in the Anglophone academy by treating the labelling of Islam and Muslim actors as radical as a particular scholarly practice. I told a colleague once that Wheatley is funny. We were making small talk at a conference in a middling New England town, likely not too far from where Wheatley’s friend, Obour Tanner, settled for a time—while her hometown was occupied by British soldiers—in 1778 and 1779. I saw my colleague’s surprise. I told her about Thornton’s absurd request and Wheatley’s joke. With a bit of concern, she asked me, “How do you know that it’s funny? How do you know Wheatley is joking? Maybe she’s articulating a kind of anxiety.” Because I didn’t have Thornton’s letter handy and couldn’t show her Wheatley’s “Now to be Serious,” I responded with my own questions: “Since when are anxiety and humor mutually exclusive? Aren’t some of the funniest people anxious?” We were left at an impasse. She was left with the implausibility of a funny Wheatley, and I was left with a nagging question: Why can’t we imagine that a twenty-one-year-old woman would tell jokes? The answer, I now suspect, is that it’s in part because of our dependency on Wheatley’s poetry. Her poems offer readers what they know to expect—references to Africa, enslavement, or even complicity and complacency, and at times, resistance. Her letters don’t. They aren’t extraordinary or unique. They don’t recount an escape, and they don’t always tell a compelling story. They do share in very quotidian ways what might annoy her, what she might love, and what makes her laugh.

I told a colleague once that Wheatley is funny. We were making small talk at a conference in a middling New England town, likely not too far from where Wheatley’s friend, Obour Tanner, settled for a time—while her hometown was occupied by British soldiers—in 1778 and 1779. I saw my colleague’s surprise. I told her about Thornton’s absurd request and Wheatley’s joke. With a bit of concern, she asked me, “How do you know that it’s funny? How do you know Wheatley is joking? Maybe she’s articulating a kind of anxiety.” Because I didn’t have Thornton’s letter handy and couldn’t show her Wheatley’s “Now to be Serious,” I responded with my own questions: “Since when are anxiety and humor mutually exclusive? Aren’t some of the funniest people anxious?” We were left at an impasse. She was left with the implausibility of a funny Wheatley, and I was left with a nagging question: Why can’t we imagine that a twenty-one-year-old woman would tell jokes? The answer, I now suspect, is that it’s in part because of our dependency on Wheatley’s poetry. Her poems offer readers what they know to expect—references to Africa, enslavement, or even complicity and complacency, and at times, resistance. Her letters don’t. They aren’t extraordinary or unique. They don’t recount an escape, and they don’t always tell a compelling story. They do share in very quotidian ways what might annoy her, what she might love, and what makes her laugh. BIOGRAPHY AT ITS BEST

BIOGRAPHY AT ITS BEST Last week’s announcement by drug behemoth Pfizer that its 5-day pill regimen powerfully curbs many early SARS-CoV-2 infections opens a new chapter in the battle against the virus. In a clinical trial that an independent monitoring group halted early because the experimental therapy appeared so effective, it slashed hospitalizations by 89% among those treated within 3 days of symptom onset. If Pfizer’s drug candidate passes muster with regulators, it could join molnupiravir, a pill recently developed by Merck & Co. that received approval last week in the United Kingdom, as the first oral medications proved to stop COVID-19 from progressing to severe disease.

Last week’s announcement by drug behemoth Pfizer that its 5-day pill regimen powerfully curbs many early SARS-CoV-2 infections opens a new chapter in the battle against the virus. In a clinical trial that an independent monitoring group halted early because the experimental therapy appeared so effective, it slashed hospitalizations by 89% among those treated within 3 days of symptom onset. If Pfizer’s drug candidate passes muster with regulators, it could join molnupiravir, a pill recently developed by Merck & Co. that received approval last week in the United Kingdom, as the first oral medications proved to stop COVID-19 from progressing to severe disease. When the interwar Conservative leader and three-time prime minister Stanley Baldwin was asked if any great thinker had influenced him, he replied: “Sir Henry Maine”. The Victorian jurist, Baldwin continued, interpreted the history of society as a grand advance from societies based on hierarchy and status to ones founded on contract and consent: an inspiring vision of human progress. Then, what looked like an expression of puzzlement came over the wily elder statesman’s face. “Or was it,” he asked, “the other way round?”

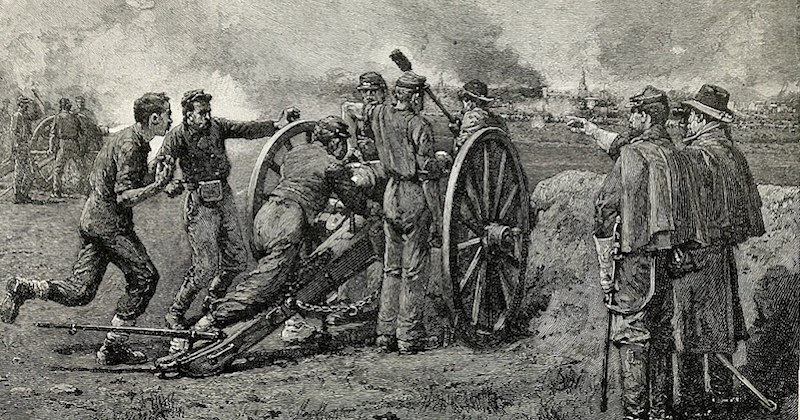

When the interwar Conservative leader and three-time prime minister Stanley Baldwin was asked if any great thinker had influenced him, he replied: “Sir Henry Maine”. The Victorian jurist, Baldwin continued, interpreted the history of society as a grand advance from societies based on hierarchy and status to ones founded on contract and consent: an inspiring vision of human progress. Then, what looked like an expression of puzzlement came over the wily elder statesman’s face. “Or was it,” he asked, “the other way round?” On the last day of October 1895, a letter was sent to Stephen Crane by the corresponding editor of The Youth’s Companion inviting him to submit work to the magazine: “In common with the rest of mankind we have been reading The Red Badge of Courage and other war stories by you… and feel a strong desire to have some of your tales.” Advertising itself as “an illustrated Family Paper,” the Companion was a national institution with an immense readership that began its life in 1827 and remained on the American scene for more than 100 years. Never more popular than in the 1890s, it published work by every important writer from Mark Twain to Booker T. Washington, and, as the corresponding editor pointed out in his letter to Crane, “the substantial recognition which the Companion gives to authors is not surpassed in any American periodical.” On top of that, it paid well.

On the last day of October 1895, a letter was sent to Stephen Crane by the corresponding editor of The Youth’s Companion inviting him to submit work to the magazine: “In common with the rest of mankind we have been reading The Red Badge of Courage and other war stories by you… and feel a strong desire to have some of your tales.” Advertising itself as “an illustrated Family Paper,” the Companion was a national institution with an immense readership that began its life in 1827 and remained on the American scene for more than 100 years. Never more popular than in the 1890s, it published work by every important writer from Mark Twain to Booker T. Washington, and, as the corresponding editor pointed out in his letter to Crane, “the substantial recognition which the Companion gives to authors is not surpassed in any American periodical.” On top of that, it paid well. The major food staples are essential to human survival. Chocolate and coffee are not essential, but try to imagine a world without them. One of the numerous concerns with climate change is that many species will lose their habitats. Scientists are projecting that, in the coming decades, this could lead to the extinction of many crops, including cacao and coffee plants.

The major food staples are essential to human survival. Chocolate and coffee are not essential, but try to imagine a world without them. One of the numerous concerns with climate change is that many species will lose their habitats. Scientists are projecting that, in the coming decades, this could lead to the extinction of many crops, including cacao and coffee plants. Capitalism has had a strange relation to the history of the United States. Whereas most societies of the Euro-Atlantic world have defined their histories at least in part around their transition from feudalism to capitalism or their complex (and often explosive) encounters with the latter, the history of the British North American colonies and then the United States has generally assumed a simultaneity in origins. The historian Carl Degler once wrote that capitalism came to North America “on the first ships,” and as simplistic as that might sound, he captured a wider sense that private property, acquisitiveness, and individualism were the foundations on which this country was built.

Capitalism has had a strange relation to the history of the United States. Whereas most societies of the Euro-Atlantic world have defined their histories at least in part around their transition from feudalism to capitalism or their complex (and often explosive) encounters with the latter, the history of the British North American colonies and then the United States has generally assumed a simultaneity in origins. The historian Carl Degler once wrote that capitalism came to North America “on the first ships,” and as simplistic as that might sound, he captured a wider sense that private property, acquisitiveness, and individualism were the foundations on which this country was built.