Month: November 2021

Andrew Sullivan speaks with Steven Pinker on rationality in our tribal times

Yanis Varoufakis: A Progressive Monetary Policy Is the Only Alternative

Yanis Varoufakis in Project Syndicate:

As the coronavirus pandemic recedes in the advanced economies, their central banks increasingly resemble the proverbial ass who, equally hungry and thirsty, succumbs to both hunger and thirst because it could not choose between hay and water. Torn between inflationary jitters and fear of deflation, policymakers are taking a potentially costly wait-and-see approach. Only a progressive rethink of their tools and aims can help them play a socially useful post-pandemic role.

As the coronavirus pandemic recedes in the advanced economies, their central banks increasingly resemble the proverbial ass who, equally hungry and thirsty, succumbs to both hunger and thirst because it could not choose between hay and water. Torn between inflationary jitters and fear of deflation, policymakers are taking a potentially costly wait-and-see approach. Only a progressive rethink of their tools and aims can help them play a socially useful post-pandemic role.

Central bankers once had a single policy lever: interest rates. Push down to revitalize a flagging economy; push up to rein in inflation (often at the expense of triggering a recession). Timing these moves, and deciding by how much to move the lever, was never easy, but at least there was only one move to make: push the lever up or down. Today, central bankers’ work is twice as complicated, because, since 2009, they have had two levers to manipulate.

Following the 2008 global financial crisis, a second lever became necessary, because the original one got jammed: Even though it had been pushed down as far as possible, driving interest rates to zero and often forcing them into negative territory, the economy continued to stagnate. Taking a page from the Bank of Japan, major central banks (led by the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England) created a second lever, known as quantitative easing (QE).

More here.

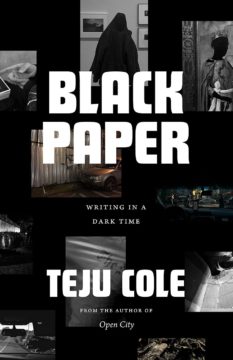

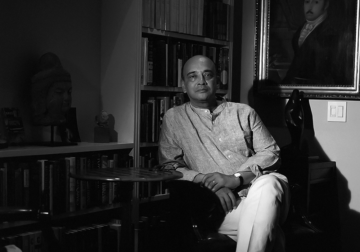

Teju Cole Interview: My Looking Became Sacred

On Edward Said’s Love Of Music And Late Beethoven

Teju Cole at Bookforum:

Edward Said loved music, and I loved his love of music as well as the musicality that characterized everything he did. Because of his writings on late style, I think of him in connection with Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 15, op. 132. This was Beethoven’s thirteenth quartet, but the fifteenth in order of publication. It’s the kind of work that tempts one to agree with the strange notion that there is such a thing as pure music, music better than any possible performance. This is a romantic idea, and it’s probably not true, since music exists in the hearing, not on the page. But listening to Beethoven’s Op. 132, you can see why people think so. Within the written tradition of Western classical music, as in all genres of music, there is music that exhausts superlatives. Late Beethoven emerges coherently out of mature Beethoven, and mature Beethoven is an extension and fulfillment of early Beethoven. These are major shifts and distinct modes of evolution, but they are not radical breaks.

Edward Said loved music, and I loved his love of music as well as the musicality that characterized everything he did. Because of his writings on late style, I think of him in connection with Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 15, op. 132. This was Beethoven’s thirteenth quartet, but the fifteenth in order of publication. It’s the kind of work that tempts one to agree with the strange notion that there is such a thing as pure music, music better than any possible performance. This is a romantic idea, and it’s probably not true, since music exists in the hearing, not on the page. But listening to Beethoven’s Op. 132, you can see why people think so. Within the written tradition of Western classical music, as in all genres of music, there is music that exhausts superlatives. Late Beethoven emerges coherently out of mature Beethoven, and mature Beethoven is an extension and fulfillment of early Beethoven. These are major shifts and distinct modes of evolution, but they are not radical breaks.

more here.

Can The Memoir Capture The Mysteries Of Childhood?

John Banville at The Nation:

Any account of childhood written by an adult might quickly become a work of adult art, presenting the child’s world, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility foreign to the experiences of being young. With his intensely concentrated gaze and voluptuous yet exact prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a work of vivid immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats’s poetry: Brought this close up to what it feels like to be a child, or for that matter an adult, Wollheim helps us see with awful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be alive.

Any account of childhood written by an adult might quickly become a work of adult art, presenting the child’s world, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility foreign to the experiences of being young. With his intensely concentrated gaze and voluptuous yet exact prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a work of vivid immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats’s poetry: Brought this close up to what it feels like to be a child, or for that matter an adult, Wollheim helps us see with awful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be alive.

Afitting epigraph to Germs could be Philip Larkin’s stark yet somehow comic line “Life is first boredom, then fear.”

more here.

AI Generates Hypotheses Human Scientists Have Not Thought Of

Robin Blades in Scientific American:

Electric vehicles have the potential to substantially reduce carbon emissions, but car companies are running out of materials to make batteries. One crucial component, nickel, is projected to cause supply shortages as early as the end of this year. Scientists recently discovered four new materials that could potentially help—and what may be even more intriguing is how they found these materials: the researchers relied on artificial intelligence to pick out useful chemicals from a list of more than 300 options. And they are not the only humans turning to A.I. for scientific inspiration.

Electric vehicles have the potential to substantially reduce carbon emissions, but car companies are running out of materials to make batteries. One crucial component, nickel, is projected to cause supply shortages as early as the end of this year. Scientists recently discovered four new materials that could potentially help—and what may be even more intriguing is how they found these materials: the researchers relied on artificial intelligence to pick out useful chemicals from a list of more than 300 options. And they are not the only humans turning to A.I. for scientific inspiration.

Creating hypotheses has long been a purely human domain. Now, though, scientists are beginning to ask machine learning to produce original insights. They are designing neural networks (a type of machine-learning setup with a structure inspired by the human brain) that suggest new hypotheses based on patterns the networks find in data instead of relying on human assumptions. Many fields may soon turn to the muse of machine learning in an attempt to speed up the scientific process and reduce human biases.

In the case of new battery materials, scientists pursuing such tasks have typically relied on database search tools, modeling and their own intuition about chemicals to pick out useful compounds. Instead a team at the University of Liverpool in England used machine learning to streamline the creative process. The researchers developed a neural network that ranked chemical combinations by how likely they were to result in a useful new material. Then the scientists used these rankings to guide their experiments in the laboratory. They identified four promising candidates for battery materials without having to test everything on their list, saving them months of trial and error.

More here.

The developing world has much bigger problems than climate change

From Spiked:

Heralding the start of the COP26 climate talks yesterday, UK prime minister Boris Johnson warned that the world is ‘one minute to midnight’ in its fight against climate change. The world leaders gathered in Glasgow say they are saving the planet from an existential threat. But does the fate of humanity really hang in the balance? And could climate alarmism do more harm than good?

Bjorn Lomborg is a climate economist and a self-described sceptical environmentalist. His latest book is False Alarm: How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts the Poor, and Fails to Fix the Planet. He joined Brendan O’Neill for the latest episode of his podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show, to talk about where the world is going wrong on climate change. What follows is an edited extract from their conversation. Listen to the full episode here.

Brendan O’Neill: At COP26, there will be lots of discussion, lots of statements and lots of dashed hopes and ambitions. What do you make of global gatherings of this kind? Do they do any good in terms of tackling climate change or making the world a better place?

Bjorn Lomborg: They probably make the world a slightly better place. But the giveaway is in the number 26 – this is the 26th time that we have tried this. We have been trying since 1992, when we signed the Rio Convention. The entire rich world failed to follow through on it. Then we had the Kyoto Protocol and again most parties failed to live up to their promises. Then we had the Paris Agreement and now we have Glasgow. The Glasgow conference is supposed to go even further than Paris did.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

A Dispatch From Seattle or, Nervous in the Hot Zone

Yes, we’re scared but we also make

zombie apocalypse jokes

By texts. I don’t know when I’ll see

my friends in person again.

We don’t want to panic and overreact

but we don’t want

To underreact. Some of my friends

are still hosting parties.

Some of them are still planning

to take their previously

Scheduled trips overseas. Some are

the polite looters

Who are buying all the toilet paper

in Seattle.

“Good for you,” I text to one of them.

“You’ll be

The most hygienic and well-stocked

shitter in the city.”

Some of my fellow Native Americans

are performing

The highly sacred Indigenous shrug,

as in, “Dude,

They’re not giving us smallpox

blankets.”

But, hey, it’s the Trumps. Their

wicked incompetence

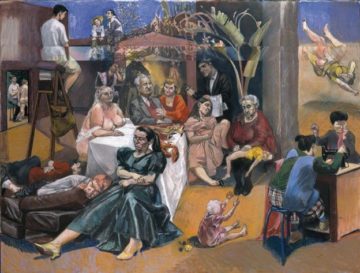

Paula Rego: Yes, With A Growl

Morgan Meis in The Easel:

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream.

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream.

The artist is Paula Rego. Rego is originally from Portugal (b. 1935) but has lived much of her life in England. Her work has been celebrated in England and to some degree in her native Portugal, but is not as well known elsewhere. She exhibited with the so-called London Group in the 1960s, a group that included David Hockney, Barbara Hepworth, and Frank Auerbach. Recently, The Tate has mounted an exhibit billed as “the UK’s largest and most comprehensive retrospective of Paula Rego’s work to date.” Critical response to the show has been rapturous and widespread. At eighty-six years of age, Rego seems finally to be getting the recognition she deserves.

More here.

UN Secretary-General: COP26 Must Keep 1.5 Degrees Celsius Goal Alive

António Guterres at COP26 World Leaders Summit:

Dear Prime Minister Boris Johnson, I want to thank you and COP President Alok Sharma for your hospitality, leadership, and tireless efforts in the preparation of this COP.

Dear Prime Minister Boris Johnson, I want to thank you and COP President Alok Sharma for your hospitality, leadership, and tireless efforts in the preparation of this COP.

Your Royal Highnesses, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The six years since the Paris Climate Agreement have been the six hottest years on record.

Our addiction to fossil fuels is pushing humanity to the brink.

We face a stark choice: Either we stop it — or it stops us.

It’s time to say: enough.

Enough of brutalizing biodiversity.

Enough of killing ourselves with carbon.

Enough of treating nature like a toilet.

Enough of burning and drilling and mining our way deeper.

We are digging our own graves.

More here.

How Hidden Technology Transformed Bowling

The JFK Cover-Up Strikes Again

James K. Galbraith in Project Syndicate:

Brood with me on the latest delay of the full release of the records pertaining to the murder of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. That was 58 years ago. More time has passed since October 26, 1992, when Congress mandated the full and immediate release of almost all the JFK assassination records, than had elapsed between the killing and the passage of that law.

Brood with me on the latest delay of the full release of the records pertaining to the murder of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. That was 58 years ago. More time has passed since October 26, 1992, when Congress mandated the full and immediate release of almost all the JFK assassination records, than had elapsed between the killing and the passage of that law.

The late Senator John Glenn of Ohio – an astronaut-hero of the Kennedy era – wrote the 1992 law. It stipulates that “all Government records concerning the assassination … should carry a presumption of immediate disclosure, and all records should be eventually disclosed.” The law states that “only in the rarest cases is there any legitimate need for continued protection of such records.”

Congress was precise in specifying where such a need might exist. Protecting the identity of an intelligence agent who “currently requires protection” was one case. Likewise, any intelligence source or method “currently utilized” deserved protection. In some cases, privacy concerns might be paramount. Finally, there was language exempting any other matter relating to “defense, intelligence operations, or the conduct of foreign relations, the disclosure of which would demonstrably impair the national security of the United States.”

More here.

Technofeudalism: Varoufakis and Zizek

How Special Is Science?

Philip Ball at Marginalia Review:

Just how experimentally constrained scientific theories are is a matter that has long been debated (and still is) by philosophers of science. And it’s surely no coincidence that they, like historians, are another scholarly group regularly dismissed and belittled by some practicing scientists as being irrelevant to the daily business of science. But in any event, many scientists seem determined to regard science and the knowledge it produces in Platonic terms: as rising rapidly above the histories, personalities, and social milieu that generate it.

Just how experimentally constrained scientific theories are is a matter that has long been debated (and still is) by philosophers of science. And it’s surely no coincidence that they, like historians, are another scholarly group regularly dismissed and belittled by some practicing scientists as being irrelevant to the daily business of science. But in any event, many scientists seem determined to regard science and the knowledge it produces in Platonic terms: as rising rapidly above the histories, personalities, and social milieu that generate it.

Sure, they might say, Darwinism was misused in its early days, when it was still poorly understood, to support racism, eugenics and a host of other prejudices of the times. But now we really know what it means! And this notwithstanding the fact that still today leading scientists will argue about whether natural selection makes eugenics meaningfully possible in principle (while new biomedical technologies resurrect its spectre), or whether there are genetic distinctions that give rise to different characteristics between racial groups. The idea that all dubious sociopolitical considerations have long since been sifted out of such scientific theories is ludicrous and ahistorical special pleading.

more here.

On Judy Chicago’s ‘Forever de Young’

Dodie Bellamy at Artforum:

GIDDY FROM SIPPING FLUTES of the de Young Museum’s prosecco, my friend Karen and I quickly realized that from the VIP section, the view of Judy Chicago’s smoke sculpture, Forever de Young, was going to suck. Since we were standing to the side of the huge pyramid-shaped scaffolding that was holding the canisters of colored pigments that would be “released” into the air, we knew we would not be able to see the whole picture. We scanned for a better vantage point but were cordoned off, and the rest of the crowd formed a dense mass that looked impossible to insert ourselves into. So we hunkered down with museum patrons and low-level journalists, and waited, as the de Young instructed us, for Chicago to “pull the trigger at just the right moment” and set the extravaganza in motion.

GIDDY FROM SIPPING FLUTES of the de Young Museum’s prosecco, my friend Karen and I quickly realized that from the VIP section, the view of Judy Chicago’s smoke sculpture, Forever de Young, was going to suck. Since we were standing to the side of the huge pyramid-shaped scaffolding that was holding the canisters of colored pigments that would be “released” into the air, we knew we would not be able to see the whole picture. We scanned for a better vantage point but were cordoned off, and the rest of the crowd formed a dense mass that looked impossible to insert ourselves into. So we hunkered down with museum patrons and low-level journalists, and waited, as the de Young instructed us, for Chicago to “pull the trigger at just the right moment” and set the extravaganza in motion.

Until I got here, I wasn’t sure the event was going to happen. Last March, Chicago’s Living Smoke performance in Palm Desert was cancelled because of environmental concerns.

more here.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Art of Nonfiction No. 10

Interview with David Remnick in The Paris Review:

Fifty years ago, at a harp recital in Gloucestershire, a retired British military officer with a clipped aristo accent came across a brown-skinned teenager. “I say, old chap, do you speak English?” the officer said. As a story in Yale’s New Journal recounted, the young man—Kwame Anthony Akroma-Ampim Kusi Appiah—replied, “Why don’t you ask my grandmother?”

Fifty years ago, at a harp recital in Gloucestershire, a retired British military officer with a clipped aristo accent came across a brown-skinned teenager. “I say, old chap, do you speak English?” the officer said. As a story in Yale’s New Journal recounted, the young man—Kwame Anthony Akroma-Ampim Kusi Appiah—replied, “Why don’t you ask my grandmother?”

“Who, may I ask, is your grandmother?” the retired officer said.

“Lady Cripps.”

Lady Cripps was Isobel Cripps, the widow of Sir Stafford Cripps, a Christian socialist and Labour politician who had been chancellor of the exchequer and the Crown’s ambassador to the Soviet Union; he was known for his stalwart desire to relinquish Britain’s imperial possessions, from Calcutta to Accra. In 1953, the year of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, Stafford and Isobel’s daughter Peggy married Joe Appiah, kinsman of Ashanti kings and a leader of the Ghanaian independence movement. (The marriage would help inspire the film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.) A year later, the Appiahs’ first child and only son was born.

When Anthony was growing up in Kumasi, the capital of the Ashanti region of Ghana, the Appiah household was a locus of political and literary conversation. Among the visitors were the historian and activist C. L. R. James, the Pan-Africanist George Padmore, and the novelist Richard Wright. Joe Appiah instilled in his son a sense of global citizenship and family honor. As Anthony once wrote, “I found myself remembering my father’s parting words, years ago, when I was a student leaving home for Cambridge—I would not see him again for six months or more. I kissed him in farewell, and, as I stood waiting by the bed for his final benediction, he peered at me over his newspaper, his glasses balanced on the tip of his nose, and pronounced: ‘Do not disgrace the family name.’ Then he returned to his reading.”

More here.

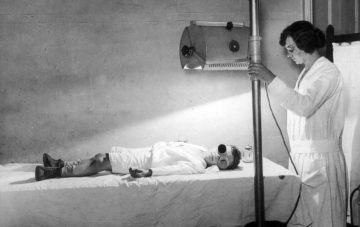

Should Booster Shots Be Required? This Covid question played out long ago, in the fight against smallpox in 1872

Mark Fischetti in Scientific American:

Vaccine booster shots for COVID have recently been approved and are being rolled out widely. Wariness about boosters is still evident, however, along with debate over whether vaccinations should be required. All this seems new to us in 2021, but a similar situation played out in the U.S. and globally way back in 1872, when smallpox was raging. Scientific American published an article about the science, fears and debate over “revaccination”—boosters—and the discussion then is eerily parallel to the COVID discourse right now.

Vaccine booster shots for COVID have recently been approved and are being rolled out widely. Wariness about boosters is still evident, however, along with debate over whether vaccinations should be required. All this seems new to us in 2021, but a similar situation played out in the U.S. and globally way back in 1872, when smallpox was raging. Scientific American published an article about the science, fears and debate over “revaccination”—boosters—and the discussion then is eerily parallel to the COVID discourse right now.

The article is reprinted below; it is a fascinating and pretty quick read. The alarming disease was spreading, people were afraid of contagion, the sick were being quarantined, and notably, there was great worry about a variant that could make smallpox much more deadly. Data from Prussia, where law required revaccination every seven years, showed that death by smallpox was rare, compared with higher rates in other parts of the world, so the editors expressed support for revaccination. Scientists were trying to determine how long to wait after initial inoculation before boosters were given. The editors also said that if there were a law requiring vaccination and revaccination, that action could end the scourge, yet they wondered whether such a law could be enforced.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Different Names for Lamotrigine

—after Sam Sax

Bitter thing—swallowed

…….. with bread, cake,

a curtain of water closing my throat,

……..anything to keep from tasting

the slight in my magician’s hand.

……..Magic is any science

you do not understand. So, too,

……..is God. Faith is

the way I trust the bitter taste will

……..turn me sweet; prayer

is how I start every day with it

……..on my tongue

before any lover, before opening

……..the window to let

the morning sun make shadows

……..where there were none

before. My body is a haunted house

……..cracking under

its own weight. Love is anything that

……..banishes the ghosts.

by Jaz Sufi

from Pank Magazine, poetry 13.1, 2018

The Scandal of Philosophy

by Dwight Furrow

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Today, few philosophers believe philosophy is a way of life, let alone the fullest and most complete way of life. Or if they do believe it, they won’t admit it in public. Only a handful of scholars, those studying ancient Greek ethics, have much to say about wisdom. Few think the question of the best human life has an answer, and if philosophy is a way of life, it consists of trolling rivals at department meetings and writing journal articles for an audience of ten specialists.

The scandal is not that modern life has moved on from issues the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought were important. Surely, the question of how one ought to live remains a pertinent question for anyone to ask. The scandal is that philosophy no longer thinks of itself as providing a guide to life and seems unconcerned about this. The question we fear most coming from non-academics is “What is your philosophy of life?” In public, the question is met with embarrassed silence. In private, it is a source of mirth and derision that someone is so jejune as to think such a thing is something philosophers ought to have. Read more »