by Leanne Ogasawara

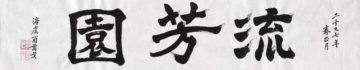

I went walking in a garden of poems. It was a perfect autumn day. And the garden, located within the confines of the Huntington Library in Pasadena, is said to be the finest classical garden outside of China. It is called the Garden of Flowing Fragrance 流芳園.

What is the flowing fragrance of beauty? Of virtue?

What is the fragrance of a perfect autumn day?

The Flowing Fragrance was inspired by the centuries-old Chinese tradition of private scholars’ gardens. With its many pavilions linked by courtyards and covered walkways surrounding the lotus-filled Lake of Reflected Fragrance, it is the perfect place to wander. Imagination on fire as you pause and notice the many works of calligraphy, integrated so beautifully in the garden, you might start to believe yourself walking inside a poem.

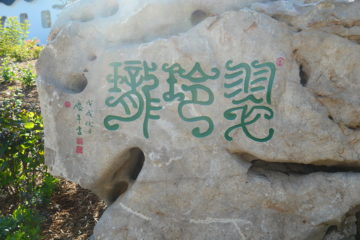

Each pavilion and bridge is adorned with evocative names. And there are snippets of verse found incised on rocks tucked in surprising corners of the garden amidst the flowering trees.

2018

Bird-and-worm script 鳥蟲書

Verdant Microcosm 翠玲瓏 , by Tang Qingnian, is incised in green on a rock set before the entrance to the western slope of the garden, which is designed for the study, creation, and display of penjing 盆景 (miniature potted landscapes, like Japanese bonsai). Written in Bird-Worm Seal Script, an ancient form of writing sometimes found in bronze inscriptions, Tang’s creation is striking. Four times now, I have observed people stopping in front of it, wondering aloud: “Is that Chinese?”

Or there is my favorite. Treading the Void 凌虛, by Wang Mansheng, an artist and calligrapher whose talent is off-scale. His ancient characters are also totally new, as he combines different styles to evoke the perfume of the past, bringing it forward into the clear and graceful lines of “now.”

In Japan, literary tropes evolved over the centuries about certain places. For example, the pines and the moon in Matsushima. Even today, Matsushima is considered one of the great “poetic places” of the country. Such poetic tropes about place are known, in Japanese, as utamakura (literally, “pillow poem”). These images trigger images of the place in people’s minds, even when they visit them only in their imagination. In this way, special places become poems.

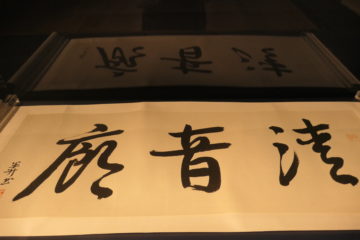

On the pavilions, poetic couplets appear like water spilling down the columns.

The first time I visited the newly opened part of the Chinese garden, I marveled that the Huntington had not only acquired the work of so many well-known contemporary calligraphers, –masters such as Bai Qianshen, Michael Cherney, Tang Qingnian, Wang Mansheng, Wan-go Weng, Grace Chu, Fu Shen, Lo Ch’ing, Zhu Chengjun, and Terry Yuan– but had expertly transferred their work onto rocks or pillars and plaques inside the pavilions.

Wang Mansheng 王滿晟

Seal-clerical script 漢簡書

Curators must have struggled over how to make the work accessible to an American audience. Linguistic and cultural hurdles make it difficult enough in a museum to access Chinese calligraphy, but to appreciate the work out in the garden is more challenging.

Not to state the obvious, but if you can’t read the calligraphy, how can you best approach the work? Museums might address this problem with explanations of form and materials that deepen the experience. While it can be greatly appreciated for its formal aesthetic qualities, calligraphy is not abstract art. It is also not craft. In East Asia, it is a fine art, informing many others—from ink painting and dance to formal garden design.

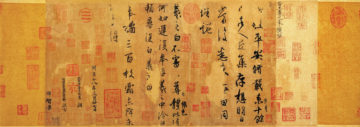

Take for example the custom of kyokusui 曲水- meaning a “meandering stream” – found in the design of formal Japanese gardens. This design element refers to the famous gathering at Orchid Pavilion and the celebrated work of calligraphy penned by Wang Xizhi.

Even during his lifetime, he is called the “god of calligraphy” in China—and certainly with his Preface of the Orchid Pavilion– the legend of Wang Xizhi was forever established. The year was 352 and Master Wang invited 42 literary figures of the day (his friends) to gather along a gently flowing stream to play the ultimate literati drinking game. Small cups made from lotus leaves were filled with wine and floated downstream. The scholars, sitting spread out along the banks of the stream, composed poems on a set theme. If the floating lotus cup reached a scholar before he completed his poem, then his task was to down the cup of wine.

By the end of the day, the scholars had composed thirty-seven poems, and Wang Xizhi, in an explosive burst of energy, took up his brush and transcribed all the poems in his dazzling running script style, adding the famous preface for good measure. The following day, Wang sat down to re-write his work more carefully. But he was unable to reproduce his mastery, because it was already perfection.

One of the most treasured works of art held in the National Palace Museum in Taipei is a short three-line piece of calligraphy called Presenting Oranges. The original—now lost—was written in the fourth century by Wang Xizhi. As the greatest Chinese calligrapher of all time, anything in Wang Xizhi’s hand was priceless even during his lifetime. For over a thousand years, students of calligraphy have looked to Wang as a model. But none of his original works have survived. Instead, we have only post-seventh-century copies.

++

Every year, my calligraphy teacher in Tokyo would organize a pilgrimage to the Palace Museum in Taipei so his top students could stand in front of Presenting Oranges. Those trained in the art of writing in brush and ink are not only able to admire the work for its formal aesthetic qualities but are able to feel what it felt like to create it.

Because Chinese calligraphy is strictly grounded in rules.

And so, by following the correct stroke order in your mind, you can physically experience the speed and pressure of the brush, take pleasure in the flourishes and full stops. You breathe along, as if you were writing it yourself.

Calligraphy is a performance art: the moment the ink touches the highly-absorbent rice paper, there is no going back. No retouching. No rethinking. And so, the calligraphy—dashed off in semi-cursive script—conflates time and space to capture one precise motion through that spacetime. It reads: I present three hundred oranges. Frost has not yet fallen. I cannot get more. (*)

Over the months, as I wandered in the Chinese garden, I longed to see the originals works of calligraphy in ink on paper. So, when the Words in the Garden exhibition was announced, I was thrilled; for not only would I be able to see the original works of calligraphy used to create the inscriptions found in the garden, but there would also be opportunities for watching the artists at work—both in video and right there out in the garden or in the Flowery Brush Library, located next to the new Studio for Lodging the Mind.

Michael Cherney 秋麥 (born 1969, New York; active China)

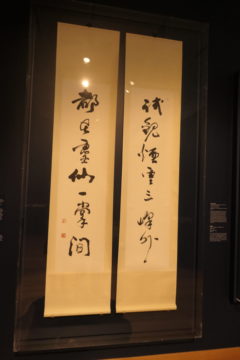

Try to contemplate the clouds and mists beyond the three peaks; all are in the palm of a numinous immortal 試觀烟雲三峰外 都在靈仙一掌間

Michael Cherney is the only American whose work is included in the garden.

Perhaps better known by his artist’s name: 秋麦 (Qiu Mai), he is a photographer whose work can be found in esteemed collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Princeton University Art Museum, and many others. I was curious to see the original ink of the couplet, which appears in frenetic running script. The catalog describes it beginning “with a character written with a brush heavily laden with ink; the liquid has so saturated the paper that an aqueous halo appears around each character.”

Would the halo be visible in ink? Oh yes… like a ballerina doing pirouettes down the stage in a blur of white and black!

In the exhibition video (which can be seen on this page along with the digitized catalog), both Cherney and Wang talk about how the act of writing calms the mind. Cherney notes that when he started his practice, he had no idea what he was getting himself into. Like me, he thought it might augment his language studies, or, in his case, inform his art. He quickly realized, as did I (!)– that a lifetime would never be enough.

In my case, in five years studying with my teacher in Tokyo, I never moved beyond the standard script. But for ten years, every morning I would wake up and practice with pencil using my kanji practice book. This was not calligraphy—it was just me trying to internalize the characters. To write them again and again until known by heart. To somehow make the characters body know-how. Then in the afternoons, I would practice with brush and ink. While I moved on to the study of tea ceremony, I continued to practice characters evert morning with pencil. This kind of routine, an activity repeated over and over, is deeply appealing to me.

Never mind the fragrance of the ink and the beautiful materials…. Just to sit and throw oneself into something is to sometimes—on a good day—quiet the mind.

One of the artists—it might have been Tang Qingnian—mentions in the video how writing comes to represent the person. In Japan, until recent times, all resumes were written by hand, since it has always been thought that writing conveys the heart of the person. There is a famous story of an emperor who, upon learning that his friend was dying a thousand miles away, sent his men on their fastest horses to try and obtain a last snippet of his writing—the hand that represented the man.

When I was hired to work at Hitachi, my boss told me later, they committed to hiring me the moment they saw my Japanese handwriting. “We knew you would be hardworking.” It is true, I worked hard and loved it.

Standing in front of Cherney’s scroll, I felt myself spilling down a waterfall in the mountains. Oh, to be able to write like that!

So much time and care went into this superb exhibition—and the best part? The curators put it all online, so everyone can enjoy and learn, and have a taste of writing from the heart.

References:

Huntington Library Exhibition Catalog: Garden of Words Part One

Museum Exhibition Page: A Garden of Words

My Notes Calligraphy in the Garden with larger images

My photos of the works installed in the garden

(*) Paragraphs about Presenting Oranges from my essay in Gulf Coast Magazine: “For the Love of Oranges”

Other:

Cloud Gate Dance Troupe: Calligraphy

Rare Tang Dynasty Copy of Wang Xizhi Work found in Japan

Favorite Books:

Another World Lies Beyond: Creating Liu Fang Yuan, the Huntington’s Chinese Garden, edited by June Li

Embodied Image

by Robert E. Harrist Jr

Kraus’ Brushes with Power

Modern Politics and the Chinese Art of Calligraphy

Sturman’s Mi Fu: Style and the Art of Calligraphy in Northern Song China Style and the Art of Calligraphy in Northern Song China

Kazuaki Tanahashi ‘s Delight in One Thousand Characters: The Classic Manual of East Asian Calligraphy

Shakyo Practice book and A Kanji Stroke Order Manual for Heart Sutra Copying

The Skills of How to Imitate Wang Xizhi’s Preface to The Poems Composed at The Orchid Pavilion Running Script Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese Calligraphy of Heart Sutra (Contrastive Version of Classical Inscription Rubbings of Dynasties)

Below, haven’t read but looks interesting!

Taction: The Drama of the Stylus in Oriental Calligraphy 石川九楊著『書-筆蝕の宇

Ishikawa, Kyuyoh; Miller, Waku