Ryan Chapman at Literary Hub:

About halfway through Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s three-hour film someone asks Yūsuke Kafuku, an actor and theater director, why he didn’t cast himself as the titular character in his production of Uncle Vanya. “Chekhov is terrifying,” he replies. “When you say his lines, it drags out the real you.”

About halfway through Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s three-hour film someone asks Yūsuke Kafuku, an actor and theater director, why he didn’t cast himself as the titular character in his production of Uncle Vanya. “Chekhov is terrifying,” he replies. “When you say his lines, it drags out the real you.”

Kafuku, played with unyielding stoicism by Hidetoshi Nishijima, has good reason to hide his real self. He’s still grieving the loss of his young daughter, and his interlocutor in this scene is Kōji Takatsuki, a volatile young actor who had an affair with Kafuku’s wife Oto shortly before her death. Takatsuki doesn’t realize that Kafuku knows about the infidelity. What’s more, Kafuku has cast him as Vanya—which the young hotshot is plainly unsuited for—in a multilingual stage production in Hiroshima. Is the cuckold tormenting his dead wife’s lover? Using the play to interrogate something darker about his marriage?

If this sounds like melodrama, Hamaguchi has declared his love of the genre. But this isn’t Douglas Sirk or Pedro Almodóvar. The plot machinations are subdued, stretched out—an acoustic cover of a pop earworm. For Hamaguchi, tone supersedes plot, and an actor’s face always says more than a line of dialogue.

More here.

We’ve talked about the very origin of life, but certain transitions along its subsequent history were incredibly important. Perhaps none more so than the transition from unicellular to multicellular organisms, which made possible an incredible diversity of organisms and structures. Will Ratcliff studies the physics that constrains multicellular structures, examines the minute changes in certain yeast cells that allows them to become multicellular, and does long-term evolution experiments in which multicellularity spontaneously evolves and grows. We can’t yet create life from non-life, but we can reproduce critical evolutionary steps in the lab.

We’ve talked about the very origin of life, but certain transitions along its subsequent history were incredibly important. Perhaps none more so than the transition from unicellular to multicellular organisms, which made possible an incredible diversity of organisms and structures. Will Ratcliff studies the physics that constrains multicellular structures, examines the minute changes in certain yeast cells that allows them to become multicellular, and does long-term evolution experiments in which multicellularity spontaneously evolves and grows. We can’t yet create life from non-life, but we can reproduce critical evolutionary steps in the lab. When I reviewed Vitamin D, I said I was about 75% sure it didn’t work against COVID. When I reviewed ivermectin, I said I was about 90% sure.

When I reviewed Vitamin D, I said I was about 75% sure it didn’t work against COVID. When I reviewed ivermectin, I said I was about 90% sure. HOW OUR BRAIN,

HOW OUR BRAIN, Most American newborns will arrive home from the hospital and start hitting their developmental milestones, to their parents’ delight. They will hold their heads up by about three months. They will sit up by six. And they will walk around their first birthday. But about 1 in 10,000 will not. They will feel limp in their caregivers’ arms, won’t lift their heads, and will never learn to sit on their own. When their alarmed parents seek medical help, the babies will be diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, a neuromuscular disease in which certain motor neurons of the spinal cord progressively deteriorate. The disease is triggered by a genetic malfunction that boils down to the gene called SMN2 (survival motor neuron 2), which causes bits of vital proteins to assemble incorrectly, resulting in progressive muscle weakness and paralysis.

Most American newborns will arrive home from the hospital and start hitting their developmental milestones, to their parents’ delight. They will hold their heads up by about three months. They will sit up by six. And they will walk around their first birthday. But about 1 in 10,000 will not. They will feel limp in their caregivers’ arms, won’t lift their heads, and will never learn to sit on their own. When their alarmed parents seek medical help, the babies will be diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, a neuromuscular disease in which certain motor neurons of the spinal cord progressively deteriorate. The disease is triggered by a genetic malfunction that boils down to the gene called SMN2 (survival motor neuron 2), which causes bits of vital proteins to assemble incorrectly, resulting in progressive muscle weakness and paralysis.

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural.

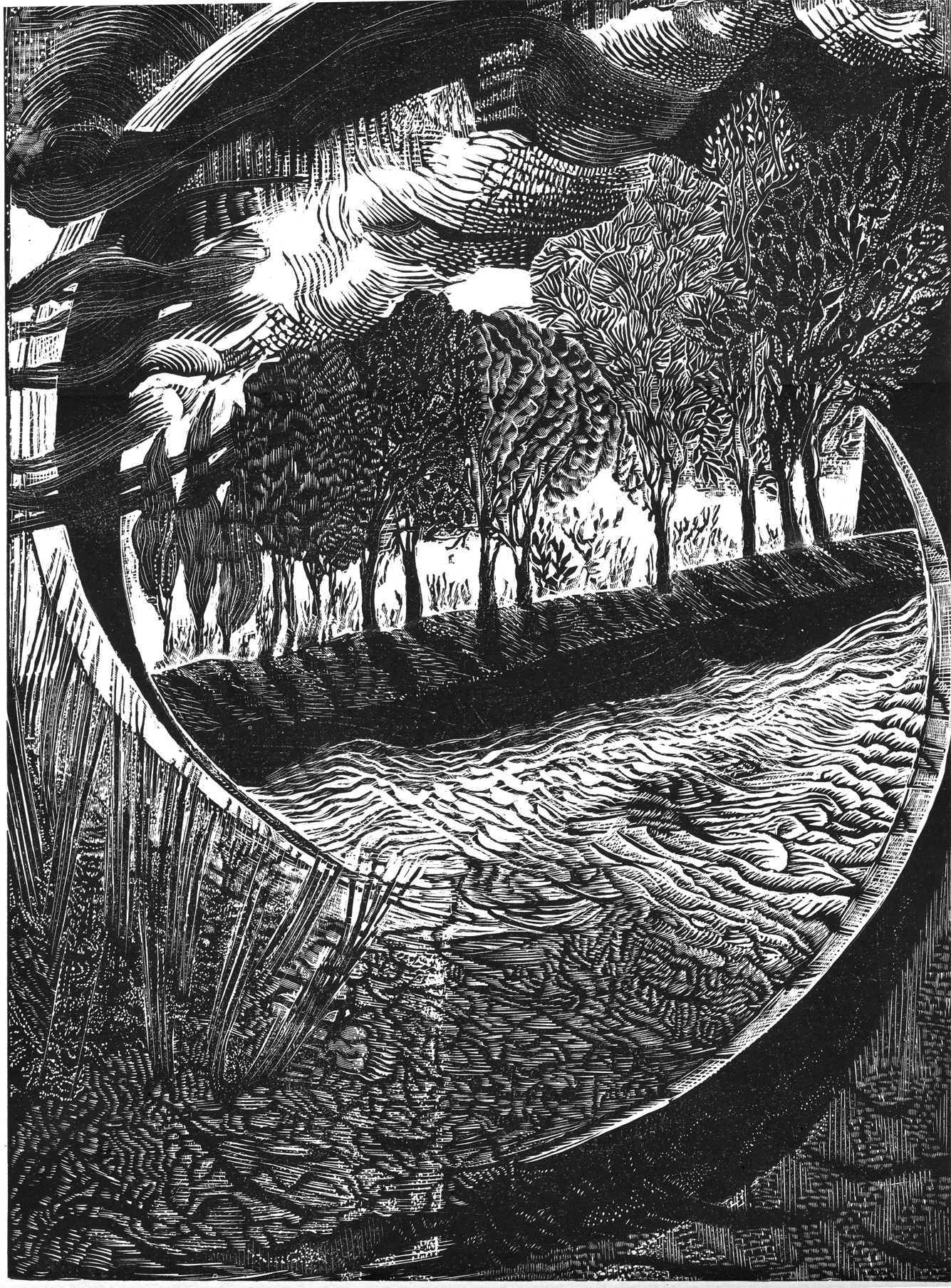

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural. Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

A scar is a shiny place with a story.