by R. Passov

When I was in the fourth grade I was held in a class through recess, most likely because letting me on the black top usually resulted in a fight. I was particularly thin-skinned and couldn’t cope with being in perhaps the only place in late-1960’s Los Angeles where children had a sense of their permanence, or at least of a place above everyone else.

I had landed in that place – Beverly Hills – from the Los Felix section of LA, now trendy, then where  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

In hindsight, it’s not surprising that I couldn’t master a narrative that to those carefree, cruel Beverly Hills kids, made any sense. And so, day-after-day, at the slightest provocation, I lashed out.

Sitting in that room, in my detention, I vaguely remember doodling through a division problem, using a long-since forgotten technique. At some point, what then seemed an ancient person stood over my shoulder, hands behind her back, wearing a frock from head to toe.

“Here,” she said, “let me show you something.” She took what I had been working on and re-wrote it, straightening it into a column, keeping the smaller number to the left, housing the bigger number under a hand-drawn awning. When the picture was finished she patiently entered into a game of subtraction, finally ending in two smaller numbers that had much to do with where she had started.

There was a little magic in what she did. I was excited at how easily I was able to reproduce her game; tingling with a sense of playful power over what I could do simply for the nonsense of it. But the magic, I came to learn, was not in the math. Rather it was in her sympathetic eyes which, for a moment, tamed me.

By my next year, we were on the move again first to cars and motels. But after a summer of chaos my father went back to prison and we went to the San Fernando Valley, to a new apartment much like the one we had left a few years prior.

From home-schooling and with the residual of investment from the kindly hall-room monitor, I was mistaken for an intelligent boy. I found myself in classes that had pacing and focus, as though I had joined a caravan on its way to somewhere known by everyone but me.

And so, again, I acted out. I wanted that caravan to slow so I could know where it had been, where it was going. But it had no mind for my wants; instead, insistent teachers insisted and, insistent in my own ways, I found myself on the blacktop again.

Soon, I was no longer in those classes. I was left to swim in the middle, able enough to drift by. By the time I reached seventh grade, my inability to grip my own life-story left me in the quite minutes that tick through every boy’s day, so, so anxious.

I fought. Sometimes in fights that, after a day of back and forth taunts, would bring the whole school out to watch, other times, alone – just two angry boys needing each other to exhaust ourselves. When I was in class and not fighting, I was a disrupter, not quite understanding the power of comedy but still using whatever means necessary to keep others from leaving me behind.

I want to say that my seventh grade math teacher – Mr. Boneparte (his real name) – taught us Algebra. But I can’t know for sure. What I do remember is a certain distractedness to him; a method of controlling his class that seemed to free him for other pursuits. Something sly even that, for reasons I never understood, gave me a certain license.

One of his techniques for saving effort called for us, after matter-of-fact, unimaginative quizzes, to hand our tests to the person behind us. Once the passing was complete, as Mr. Boneparte read off the answers we graded our fellow students. At the end of this shortcut we were called upon, one after the next, to stand and report out in a very particular format: First the raw number of correct answers, followed by the appropriate letter grade to be contained within a sentence such as ‘B as in boy.’ Then we were to spell the targeted word – B O Y.

It was a hot day toward to the end of the year and we were in a cabin on the blacktop, which said something about how far away Mr. Bonaparte was from tenure. When, during this particular grading session, my turn came, I rose. “B,” I said, “as in Birdshit.”

I could feel the frozen eyes of my fellow students. “B_I_R_D,” I spelled out then paused, feeding on the silence of the class while searching Bonaparte’s eyes, looking for clues as to the depth of my pending punishment. Then I went on: “S_H_I_T.”

I felt so good in the first moments, free of any concern for consequence. Mr. Bonaparte, as though returning from a trance, slowly walked in my direction. Eventually he reached my desk, grabbed my arm and walked me to the door. We found ourselves on a bright, hot, Valley day, standing on the small landing at the top of the stairs that gained entrance to his bungalow.

I was sure of violence, some force that would humiliate me and then of a shove toward the principal’s office. But when, after a too-long moment of silence, I looked up I saw how hard Mr. Bonaparte was trying not to laugh.

“Dam it!” he said, still gripping my arm.

“Dam it,” he said again and laughed some more. “You think I like teaching math? I’m a piano player. At Tail o’ the Cock. Come by and see me play. In the meantime, get off my case.” He told me to stand on the ledge until I heard the bell, then go on to my next class.

* * *

I granted Bonaparte his wish. By the eighth grade I had become a cliche: a bad kid following in my father’s footsteps. By the 10th grade I’d turned around somewhat, only to find that joining the other side – the legitimate crowd that woke every day without wondering where the police were – wasn’t easy.

Mr. Granapole (phonetically close to his real name) taught 10th grade math. His class began at 11:00, ended just before lunch and I knew nothing about nutrition. I had a job breaking down loads in a grocery warehouse. I’d start around 8:00 at night, work until 12:00, come home, fall asleep, wake up, go to school. I got whatever nutrition was available between the hours of 3 and 7pm, which is also when I’d stab at my homework.

Granapole had a way of keeping me on edge. If I raised my hand, he moved on before I got my answer out, as though he had already decided that no matter how hard I tried, I just wasn’t going to get there.

Before too long I felt as though certain classmates who exuded a smug confidence were being helped along by Granapole toward something they deserved. And that his leaving me behind was something I deserved.

My inability to master the subject was what Granapole expected and an essential part of who I was: someone who lacked the confidence necessary for success. The feeling of failure fed an anxiety that fought away any effort at concentrating. In the end, with a smile that said I had met his expectations, Granapole gave me a C.

Learning to master oneself is the greatest gift to be gained from an education. But along the way, too many adolescents get turned back into visions of their worst selves. I am not faulting teachers or the curriculum or blaming the many layers of hierarchy. I am generally ignorant of how math is taught today.

But I do know the value of a good teacher. Luckily for me, Mr Patton (real name) followed Mr Granapole. He came from the mid-west, I’m assuming, just because he was so straightforward, so devoid of guile, so absent of an agenda, so present. In short, Mr Patton was different.

Where Granapole looked as though he had just completed a triathlon, Patton looked as though whatever he was doing to maintain his extra pounds was something he enjoyed. He had weak hands, no forearms, thin biceps, as though he found no use for physical strength. In short, he looked vulnerable.

I believe I allowed my mind to wander far enough to realize that he had a sexuality different from mine. Unlike the over-juiced teenagers I hung with, Mr Patton did not spend his days dreaming of girls. But that’s as far as I went.

Along with his apparent vulnerability – at least as I then measured things – Patton projected an incongruous sense of serenity. That intrigued me, causing me to wonder about the life of another person.

Not about the particular. Instead he caused me to wonder about that fact that he seemed to be making choices in his life: choosing to be a math teacher, choosing not to cloak himself under the mantle of authority, choosing to allow me and my fellow students to see him as he was.

Mr. Patton taught trigonometry. I did not excel in his class. But once I succeeded in solving one of the harder test problems through an understanding that came into my mind as though, in real-time, I watched a puzzle fall together.

Like Mr. Boneparte, Mr. Patton had his own ways. Toward the end of a class, he’d walk the aisles, handing back our tests, offering small, thoughtful phrases. If I had done particularly poorly, I’d get a kind glance. Through that simple gesture, the whole class knew my grade. Yet there was no shame or sense of failure. It was a feeling of missing my own expectations, which was unfamiliar.

As he handed back that one test where I stumbled through the hardest problem, I could see the red exclamation marks encapsulating my answer. After praise for getting that one problem right, he added, “If only you did the homework.” It felt as though he was saying that my future had more to do with choices I was making than I wanted to admit.

Twenty plus years from high school, I found myself as the Treasurer of a Fortune Five Hundred Company, realizing how much I owed Mr. Patton. I went in search of him but find nothing, not a trace. He’s somewhere, or maybe not, but either way he’s not forgotten.

* * *

I was taught math as though by a succession of quilt makers, each showing me a particular patch, never the whole blanket. Each patch was its own exercise in computation, as though I was being prepared for a role as an assistant calculator to a 19th century astronomer.

Today, computation is at our fingertips.

Four days per week, at two of New Your City’s most under-resourced schools, approximately 150 4th and 5th grade students enjoy a math-enrichment program. Along with a handful of teachers, I spend an hour with kids ranging in age from 10 to 12. For the first five minutes I talk about ‘math’ – what is it? I ask. Then we go on a journey cribbed from Mario Livio’s Is “God a Mathematician.”

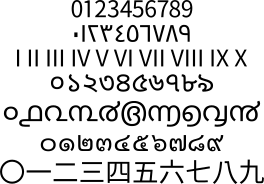

Look at the different ways languages and cultures represent a two, I say as I show the students the scribbles from different numbering systems. If we add a scribble for two to a scribble for three do we always get the scribble for five, no matter the language? If so, then is math about numbers or about rules of a game?

Would any alien see the mathematical universe the same way we do? I ask as I hand out bags randomly filled with M&M’s. (Borrowed from the Internet) The students empty the bags and, in groups, count with their fingers, then tally first the number of whole finger counts – the base – then the left overs – the ones. Three tens and four ones, a group might say.

Then, hopefully after not eating anything, we count again but this time using only the space between the knuckle creases on a single hand, (excluding thumbs, surprisingly there are twelve such spaces.) Then a student reads out – two full bases followed by ten ones: same count, different base.

Next, we play the Alien Game: I describe the number of fingers the Alien has and the students show me how the Alien forms numbers: if it’s a three- fingered Alien, for example, then her six is 20, two bases, zero ones; similarly, a seven becomes 21, two bases, one ‘1.’

I tell the kids about the possibility that there was a Native American who had collected a lot of shells that once were a type of money and how this Native American didn’t want to carry all of her shells around but realized she’d need a system that would allow her to know her shells and finally she came up with one where instead of having to remember line after line after line, one for each shell, she only had to remember one scribble; one mark that allowed her to know the full total of her shells.

Once she figured out how to do this she had abstracted the numbers from the shells. And once this was done she played with the numbers, always according to the rules laid out by Boole of Boolean Algebra fame who said math is not necessarily about quanta; math is about the rules of a game where you assign meaning to symbols and then only allow operations that keep you within the assigned meanings. Then we discuss the most surprising aspect of abstracted math – that when you least expect it, abstractions strike upon a real word counterpoint, such as the Higgs Boson.

I started this program. It’s meant to carry on in the tradition of Mr. Patton (though, for the record, I named it The Susan Wildman Foundation after Steve and Susan Wildman, who picked up where Mr. Patton left off and whose debt I can never repay.)

I am not trying to discover future mathematicians. My goals are more modest: See as many students as possible, when they get to high school, realize something familiar in their math courses and have that feeling marshal into a confidence, encouraging them to try and feel good about a B, or better yet, a B+. Most importantly, just try.