Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer — the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect — the biographer has been derided as a “post-mortem exploiter” (Henry James) and a “professional burglar” (Janet Malcolm).

To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer — the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect — the biographer has been derided as a “post-mortem exploiter” (Henry James) and a “professional burglar” (Janet Malcolm).

The critic Elizabeth Hardwick called biography “a scrofulous cottage industry,” adding that it was rarely redeemed by “some equity between the subject and the author.” One biographer of Ernest Hemingway, Hardwick wrote, seemed so enamored of “his access to the raw materials” that he produced “only an accumulation, a heap.” Similarly, a book about Katherine Anne Porter was larded with “an accumulation of the facts,” which had “the effect of a crushing army.”

A warning, then, was probably in order for Cathy Curtis, the author of “A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick.”

…The ’70s turned out to be an extraordinarily productive time for Hardwick — a decade when she wrote the essays on women and literature that were collected in “Seduction and Betrayal,” and when she polished the scenes that she collaged into “Sleepless Nights.” Curtis assiduously chronicles the literary panels, the gossip and the ailments of Hardwick’s later years, before she died in 2007, observing the rhythms of Hardwick’s work while never quite falling into sync with them. But then a march is different from a dance, even if each has its own choreography. When Hardwick was in her late 80s and still writing, she was asked why writers stop. “Writing is so hard,” she said. “It’s the only time in your life when you have to think.”

More here.

The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux.

The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux. It’s easy to mock the Corporation Formerly Known As Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook would

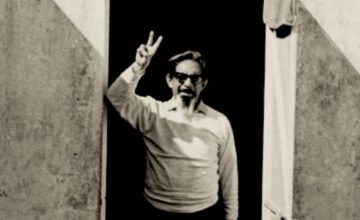

It’s easy to mock the Corporation Formerly Known As Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook would  A LITTLE OVER halfway through his 1943 novel El luto humano (Human Mourning), the Mexican writer José Revueltas inserts himself as a character so unobtrusively that it’s easy to miss. A government go-between, when hiring an assassin to kill the leader of an agricultural strike, complains, “First there was the agitation sown by José de Arcos, Revueltas, Salazar, García, and the other Communists. […] And now all over again…” It’s a sly wink at the fact that the novel’s scenario overlaps with the author’s life; it also foreshadows the way that Revueltas’s place in Mexican letters today is inextricably entwined with his dramatic biography.

A LITTLE OVER halfway through his 1943 novel El luto humano (Human Mourning), the Mexican writer José Revueltas inserts himself as a character so unobtrusively that it’s easy to miss. A government go-between, when hiring an assassin to kill the leader of an agricultural strike, complains, “First there was the agitation sown by José de Arcos, Revueltas, Salazar, García, and the other Communists. […] And now all over again…” It’s a sly wink at the fact that the novel’s scenario overlaps with the author’s life; it also foreshadows the way that Revueltas’s place in Mexican letters today is inextricably entwined with his dramatic biography. The instant recognisability of Magritte’s work has its roots not in his training at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918 but in his postwar work as a draughtsman in the city from 1922 to 1926. During this time he made artworks for advertising companies and designed wallpaper and posters. The skills garnered from the first two of these are immediately evident in Golconda, now in the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The bowler-hatted men, part Thomson and Thompson, part Gilbert and George, are as obviously Magritte’s logo as the part-eaten apple is that of a certain American computer giant. His eye for pattern was also acute. Golconda would make lovely wallpaper, and no doubt has.

The instant recognisability of Magritte’s work has its roots not in his training at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918 but in his postwar work as a draughtsman in the city from 1922 to 1926. During this time he made artworks for advertising companies and designed wallpaper and posters. The skills garnered from the first two of these are immediately evident in Golconda, now in the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The bowler-hatted men, part Thomson and Thompson, part Gilbert and George, are as obviously Magritte’s logo as the part-eaten apple is that of a certain American computer giant. His eye for pattern was also acute. Golconda would make lovely wallpaper, and no doubt has. Depending on the outcome of social conflicts, ants of the species Harpegnathos saltator do something unusual: they can switch from a worker to a queen-like status known as gamergate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell on November 4th have made the surprising discovery that a single protein, called Kr-h1 (Krüppel homolog 1), responds to socially regulated hormones to orchestrate this complex social transition.

Depending on the outcome of social conflicts, ants of the species Harpegnathos saltator do something unusual: they can switch from a worker to a queen-like status known as gamergate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell on November 4th have made the surprising discovery that a single protein, called Kr-h1 (Krüppel homolog 1), responds to socially regulated hormones to orchestrate this complex social transition. “Ever since I have been at court,” exclaimed the vidame, “the queen has always treated me with much distinction and amiability, and I have reason to believe she has had a kindly feeling for me. Yet there was nothing marked about it, and I had never dreamed of other feelings toward me than those of respect. I was even much in love with Madame de Themines. The sight of her is enough to prove that a man can have a great deal of love for her when she loves him—and she loved me.

“Ever since I have been at court,” exclaimed the vidame, “the queen has always treated me with much distinction and amiability, and I have reason to believe she has had a kindly feeling for me. Yet there was nothing marked about it, and I had never dreamed of other feelings toward me than those of respect. I was even much in love with Madame de Themines. The sight of her is enough to prove that a man can have a great deal of love for her when she loves him—and she loved me. In 1966, I was a junior at St. Louis’s Kirkwood High. After the teachers let us monkeys out at 2:50, I lazed about, often trekking to a friend’s home to talk antiwar politics or Salinger stories. I was a serious kid, some days lying on one of the twin beds in Ken Klotz’s room (his unlucky brother off in Vietnam) where we were hypnotized by Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the literary dazzle of “Visions of Johanna”: “The ghost of electricity howls from the bones of her face.” But then some days I needed a break.

In 1966, I was a junior at St. Louis’s Kirkwood High. After the teachers let us monkeys out at 2:50, I lazed about, often trekking to a friend’s home to talk antiwar politics or Salinger stories. I was a serious kid, some days lying on one of the twin beds in Ken Klotz’s room (his unlucky brother off in Vietnam) where we were hypnotized by Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the literary dazzle of “Visions of Johanna”: “The ghost of electricity howls from the bones of her face.” But then some days I needed a break. But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments.

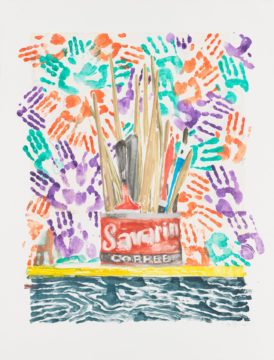

But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments. His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.”

His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.” For months, during the main

For months, during the main  It’s been more than 50 years since

It’s been more than 50 years since  The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.”

The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.”