by Dave Maier

The other day here at 3QD, philosopher Guy Elgat provided an interesting discussion of the conspiracy theory Q-Anon and some relevant philosophical issues about knowledge and rationality. In particular, he focused on a seemingly perverse response by Q-ers to our challenge to provide proof of their outlandish claims: that we “don’t have any proof there isn’t [a Q].” I had a number of reactions to this column, as well as to some of the comments from readers, but I didn’t want to dump a huge comment on the thread (plus I had to think about it), so I thought I would put my response here instead.

I get the impression that since the QAnon business is sheer madness, and thus not philosophically interesting, what interests Elgat about it is instead the apparent parallel, epistemically speaking, with the historically much more substantial question of whether God exists. (For instance, he notes that religious believers pull this same epistemic-leveling move, in discussion with atheists, as do Q-ers with us.) I find this a bit misleading, or at least confusing, and I think that in the Q case we should be a bit more choosy about what exactly the content of their controversial belief is, even if we sacrifice that potentially interesting parallel. (In fact I think religious faith is a much more complex phenomenon than simply “belief in God,” to which proofs of this or that are pretty completely irrelevant; but let’s leave God out of it entirely for now.)

Elgat’s argumentative strategy, in any case, is to assimilate the Q-er to the Cartesian skeptic, both of whom issue seemingly impossible challenges to prove them wrong: in the one case, that Q exists; in the other, that we are brains in vats and are thus massively deceived about “the external world” outside our senses. In each case, in Elgat’s telling, the challenger’s conclusion, should our proof fail, is that we thus are “in an epistemological stand-off” and must acknowledge that “since I cannot show you I am right and you cannot prove me wrong, I am perfectly within my rights, so to speak, to continue to believe in whatever I choose to believe.”

Elgat has two responses to this. Read more »

My dad was a pharmacist. He had an old-fashioned store (including an actual soda fountain and stools) and some of the old-fashioned tools of the trade: scales and eye-droppers, spatulas and ointment bases, graded flasks and beakers, amphorae, and his mortar and pestle.

My dad was a pharmacist. He had an old-fashioned store (including an actual soda fountain and stools) and some of the old-fashioned tools of the trade: scales and eye-droppers, spatulas and ointment bases, graded flasks and beakers, amphorae, and his mortar and pestle.

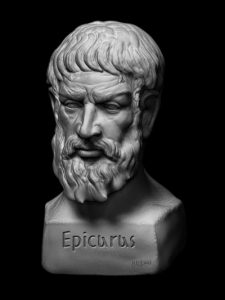

I have been a practicing Stoic for a few years now, with lulls here and there. Stoicism provides a compelling framework for living in a purposeful and ethical way. The question in my mind is, is it perhaps a little too compelling? In other words, not much fun?

I have been a practicing Stoic for a few years now, with lulls here and there. Stoicism provides a compelling framework for living in a purposeful and ethical way. The question in my mind is, is it perhaps a little too compelling? In other words, not much fun?

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

Roxane Gay’s Hunger is very, very good—the rare memoir that doubles as page-turner. I’m writing this on a flight (Gay’s passages on airplane issues are some of her best: the seatbelt extenders, having to buy two tickets) and the woman across the aisle is reading Difficult Women. “Book Twins!” she just said happily. This never happens. That Gay has reached so many is testament to her skill with empathetic connection. She writes early in Hunger that her “life is split in two, cleaved not so neatly. There is the before and after. Before I gained weight. After I gained weight. Before I was raped. After I was raped.”

Roxane Gay’s Hunger is very, very good—the rare memoir that doubles as page-turner. I’m writing this on a flight (Gay’s passages on airplane issues are some of her best: the seatbelt extenders, having to buy two tickets) and the woman across the aisle is reading Difficult Women. “Book Twins!” she just said happily. This never happens. That Gay has reached so many is testament to her skill with empathetic connection. She writes early in Hunger that her “life is split in two, cleaved not so neatly. There is the before and after. Before I gained weight. After I gained weight. Before I was raped. After I was raped.” Tim Watson’s Culture Writing surveys the border between anthropology and literature in the years following World War II. Watson provides illuminating readings of British social anthropology in relation to novels by Barbara Pym, and of North American cultural anthropology in relation to novels by Ursula Le Guin and Saul Bellow. There are also chapters on Édouard Glissant and Michel Leiris, working in the French tradition (in which the border between literary and ethnographic writing was configured differently than it was in the Anglo-American tradition). While anthropologists will find much of value in Watson’s individual readings, they may find his broader sketch of their disciplinary history to be seriously askew, as I shall suggest in what follows.

Tim Watson’s Culture Writing surveys the border between anthropology and literature in the years following World War II. Watson provides illuminating readings of British social anthropology in relation to novels by Barbara Pym, and of North American cultural anthropology in relation to novels by Ursula Le Guin and Saul Bellow. There are also chapters on Édouard Glissant and Michel Leiris, working in the French tradition (in which the border between literary and ethnographic writing was configured differently than it was in the Anglo-American tradition). While anthropologists will find much of value in Watson’s individual readings, they may find his broader sketch of their disciplinary history to be seriously askew, as I shall suggest in what follows.

What happens when a scientific journal publishes information that turns out to be false? A fracas over a recent

What happens when a scientific journal publishes information that turns out to be false? A fracas over a recent  What will a Corbyn government actually do? Brexit aside, British politics has no bigger known unknown. The prospect fills the rich with fear and the left with hope. Both sides assume that Prime Minister

What will a Corbyn government actually do? Brexit aside, British politics has no bigger known unknown. The prospect fills the rich with fear and the left with hope. Both sides assume that Prime Minister