by Akim Reinhardt

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

In a nation of nearly 4,000,000 people, the ten largest cities had a combined population of only 152,000. And half of those top ten cities did not even have 10,000 people.

Yet, even then, tensions between rural and urban interests were already evident. Urbanites, particularly elite merchants, had drawn on their power, wealth, and influence to promoting constitutional ratification. At the forefront of opposition had been small farmers.

A general theme among opponents to ratification were concerns that the new constitution aimed to create a much stronger central government. Some worried it would erode the sovereignty of the individual states. Some thought it created something too much like the despotic British government they’d just rebelled against. And some fretted about the possible loss of personal liberties; the much vaunted Bill of Rights was not part of the original document.

Debate was fierce. Historians believe it’s possible that a majority of Americans actually opposed the new Constitution. Yet it passed it eventually. During an era when voting rights were tied to personal wealth, small farmers held little political sway in most states despite their numbers. Their concerns did lead to the first 10 Amendments being added, but in the end the Federalists, particularly active in larger cities such as New York and Boston, won the day. Yet the vengeance of anti-urbanites was close at hand.

Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, was a rural Virginia plantation (and slave) owner, and openly contemptuous of cities. “The mobs of great cities add just so much to support of pure government as sores do to the strength of the human body,” he once opined.

Jefferson had also mixed views about the Constitutional Convention’s work, but stationed in France at the time, was in no position to stop it. After its ratification, he advocated a restrictive interpretation of the federal government’s powers; he was the original Constitutional Constructionist. And as the 3rd president of the United States, he doubted his own constitutional authority to consummate the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. But he did it anyway.

Why? Because, as he explained to his protégé James Madison (another rural Virginia planter, and his eventual successor in the White House): “I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries as long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get plied upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, they will become corrupt as in Europe.” Jefferson’s hatred of cities was so profound that he was willing to betray his own political values to thoroughly counter any potential urban growth, and to further his vision of a rural, agricultural republic.

Despite Jefferson’s machinations, U.S. cities grew at a phenomenal rate during the early 19th century. By 1850, the United States boasted 236 cities with an average population of 15,000. A fifth of Americans now lived in cities. And as the rural/urban divide widened, it found cultural expression by subtly feeding the increasingly rancorous debate over slavery.

During the runup to the Civil War, most Northerners opposed slavery under a philosophy called Free Soil. Free Soilers generally had little interest in extirpating slavery from the South. Rather, they sought to contain slavery and prevent its expansion into the new Western territories and states. Hardly humanitarians, many Free Soilers were actually virulent racist who actually wanted to ban free blacks as well as slaves from the new territories. Abolitionists, who opposed slavery on moral grounds and wanted to end the institution altogether, were few and far between in the North prior to the war. But their numbers were centered in the cities of New England, the nation’s most urbanized region.

At first, abolitionism was prominent only in a handful of coastal cities. But during the Civil War, the rural North largely embraced the idea. By war’s end, abolition was a major goal of the Union. And with the Union’s victory over the rural South, the influence of Northern American cities soon spread in other ways.

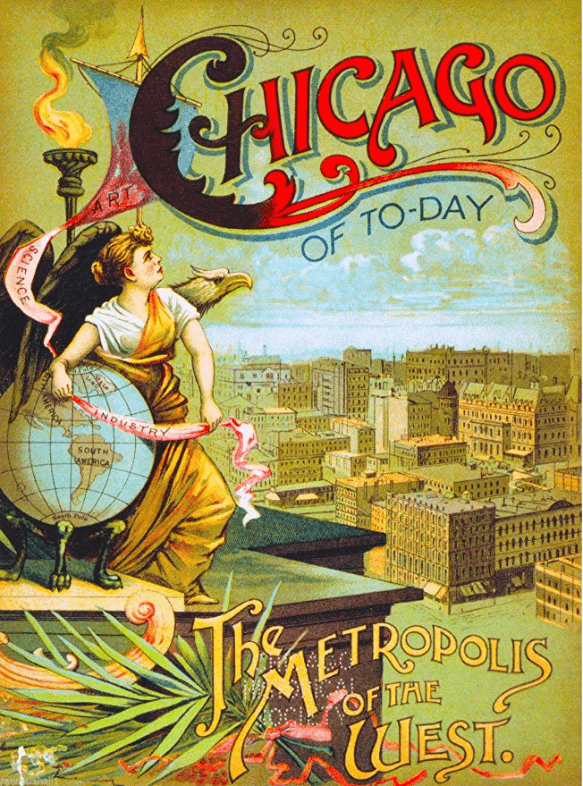

During the Gilded Age, the North drove the nation, and increasingly the North was driven by cities. As the Industrial Revolution created ever more jobs in those cities, immigrants flooded in. Between 1860-1900, the sheer number of U.S. cities grew 450%, and the population of American urbanites grew 500%. By century’s end, there were 38 cities with over 100,000 people, and three that topped a million (New York, Chicago and Philadelphia). Even the South urbanized after the Civil War, with four cities among the nation’s largest 20 by century’s end (Baltimore, New Orleans, Washington, and Louisville), and many much smaller ones now dotting its landscape. By 1920, the census revealed for the first time that a majority of Americans lived in cites.

With their increasing concentrations of capital and booming populations, American cities were poised to overturn Jefferson’s dream of an agrarian republic, which in turn led to a backlash. Amid this era of rapid urban expansion, rural/urban tensions were palpable, and anti-urban sentiments were widespread. Common cultural tropes defined cities as dangerous places rife with immorality and corruption, and teeming with dirty mobs of untrustworthy, non-Protestant, non-white immigrants (Americans of the era did not consider southern or eastern Europeans to be fully “white”). Native Northeasterner and New York City resident Horatio Alger might pen dime novels about bustling, chaotic cities full of opportunity, where a virtuous young man could, with a lot of pluck and little luck, make it big. But darker images of crime-ridden slums were also commonly woven into the cultural fabric. For example, an 1871 song by Clara Berry warns boys eager to leave the farm that:

The city has many attractions,

But think of the vices and sins,

When once in the vortex of fashion,

How soon the course downward begins

During the Gilded Age, American rural identity was shaped, in part, by anti-urban sentiments. Many rural Americans built identities for themselves not just as plain, polite, honest, hard-working, god-fearing, down home “country” folk, but also as wise anti-urbanites. The feelings were soon reciprocated. By the turn of the 20th century, popular culture increasingly exalted burgeoning cities, their wealth, and new technologies as emblems of the future and signs of inexorable progress. And urban culture increasingly patronized rural society as quaint and naive, and even derided it as backwards and stupid.

Baltimore journalist H.L. Mencken epitomized urban hostility towards the supposed ignorance and anachronistic stubbornness of rural Americans. He regaled in casting country folk as dumb rubes not to be trusted with democracy. To be fair, he also made a habit of lambasting the urban middle class. But his affection for ranting against the nation’s “forlorn backwaters” reached a crescendo during his coverage of the 1925 Scopes “monkey” trial in Tennessee. He dismissively labeled “the mob” of “ local primates” as religious zealots, “hill billies,” and “yokels.” As “morons” who, defined by “prejudices and superstitions,” promoted and embraced “simian imbecility.” As “Huns” under the sway of a “Neanderthal” banner, and threatening to overrun the nation.

Baltimore journalist H.L. Mencken epitomized urban hostility towards the supposed ignorance and anachronistic stubbornness of rural Americans. He regaled in casting country folk as dumb rubes not to be trusted with democracy. To be fair, he also made a habit of lambasting the urban middle class. But his affection for ranting against the nation’s “forlorn backwaters” reached a crescendo during his coverage of the 1925 Scopes “monkey” trial in Tennessee. He dismissively labeled “the mob” of “ local primates” as religious zealots, “hill billies,” and “yokels.” As “morons” who, defined by “prejudices and superstitions,” promoted and embraced “simian imbecility.” As “Huns” under the sway of a “Neanderthal” banner, and threatening to overrun the nation.

Amid the stereotypes and insults, and mutual suspicion and fear marking America’s rural/urban divide, cities seemed to have the upper hand. However, another shift was at hand. U.S. cities experienced their final (at least for now) major population boom during World War II. As the United States mobilized for war, factory jobs multiplied in cities across the nation, ending the Great Depression and drawing millions more to urban centers. But after the war ended, the decline of American cities began almost immediately. Many new arrivals during both world wars had been African Americans. As urban populations became more racially mixed, particularly in the East, more and more people fled overcrowded cities to brand new, lily white suburbs, the development of which were made possible by massive government subsidies for roads and housing purchases.

The middle class exodus and deindustrialization combined to ravage city finances. Drastic budget cuts and a declining quality of life encouraged yet more people to leave, pushing many older cities into something that nearly approximated a death spiral. As the cycle repeated itself over and over during the last half of the 20th century, suburbanites quickly surpassed both urbanites and rural Americans as the nation’s wealthiest, most numerous, and politically influential demographic.

Yet even as suburbia established itself as home of America’s dominant demography, it was subjected to an unremitting wave of negative stereotypes. Critics derided their sterility and conformity. Suburbs were alternately mocked and pitied for their supposed lack of culture, middle class fear mongering, and tediously long commutes. Malvina Reynolds’ 1962 song “Litle Boxes” was an early broadside.

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky tacky . . .

Little boxes all the same . . .

And the people in the houses

All went to the university,

Where they were put in boxes

And they came out all the same . . .

And they all play on the golf course

And drink their martinis dry,

And they all have pretty children

And the children go to school,

And the children go to summer camp

And then to the university,

Where they are put in boxes

And they come out all the same.

Today, less than a third of Americans live in urban centers, while not even 15% live in the nation’s rural counties. But American identities, with regards to geography, still spin largely around that simplistic dialectic.

Suburbanites are now roughly one-half the national population. Another large chunk of Americans live in small, relatively isolated metropolitan areas that are part rural and part urban, but really neither. Together, these two groups are a majority of the population. Yet, beyond themes of domesticity and bland claims of safety and good schools, they have largely been unable to craft a distinctively positive identity for themselves in the popular culture. These suburban, ex-urban, and small urbanites have been left to characterize themselves in alien terms. To define themselves by who they are not as much as who they are. To align themselves with foreign characteristics of urbane cosmpolitanism or folksy, down home goodness, depending upon which way they wish the wind to blow. And in a nation where “inner city” is a euphemism for “dangerous black people” and “fly over country” means “boring rural areas and the naive, boring people who live in them,” the choices they make can be less about positive affiliation and more about distancing oneself from negative stereotypes.

Thus, despite the fact that cities and rural areas are home to a minority of Americans, the culture of American identity construction, and the national and state politics it feeds, both still pivot on the rural/urban axis. Modern America’s red-blue divide, so fierce in its partisanship, has many dimensions, including race, gender, sexuality and social issues ranging from guns to abortions. Yet nearly all of them filter through the urban/rural divide. Urban identity is channeled through the Democratic Party, and rural identity through the Republican Party, with voters in both regions lining up lockstep on election day, often more confident in their identity than their grasp of the issues.

States with rural identities are very red. States with urban identities, often shaped by large, wealthy, influential cities with a strong gravitational pull on the surrounding suburbs (eg. LA, SF, NYC, Chicago), are very blue. Meanwhile, those that feature both distinctly rural and urban areas, grapple with contests over identity, marking them as battleground states. Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida are riven by urban/rural divides, their suburbs and isolated metropolitan areas left to slouch this way then that as they pick sides and sway one election after another.

Barack Obama successfully crafted an urbane message of modernity, tolerance, and progress that resonated with many suburban voters. More recently, Donald Trump has found success by habitually touring rural-leaning suburbs and small, isolated metropolitan areas, and rousing audiences with an equally animated, but rather rough and tumble, plain spoken message about rural values and the good ole days. That he himself is a loud, garish, foul mouthed New Yorker is, quite obviously, besides the point. People are inclined to shoot the messenger when the message his bad, and embrace him when he says what they want to hear. Both Obama and Trump know how to tell their constituents what they want to hear, which by default in today’s divided America, means deeply alienating the opposition.

Barack Obama successfully crafted an urbane message of modernity, tolerance, and progress that resonated with many suburban voters. More recently, Donald Trump has found success by habitually touring rural-leaning suburbs and small, isolated metropolitan areas, and rousing audiences with an equally animated, but rather rough and tumble, plain spoken message about rural values and the good ole days. That he himself is a loud, garish, foul mouthed New Yorker is, quite obviously, besides the point. People are inclined to shoot the messenger when the message his bad, and embrace him when he says what they want to hear. Both Obama and Trump know how to tell their constituents what they want to hear, which by default in today’s divided America, means deeply alienating the opposition.

In an early 20th century English translation of Aesop’s Fables, the country mouse and the town visit each other’s homes only to come away with a strong preference for their own lifestyle. Aesop makes clear that he believes the country mouse has the preferable circumstance. “Poverty with security is better than plenty in the midst of fear and uncertainty,” the moral reads. And each mouse is a bit judgmental, as characters are wont to be in moralistic fables. But the mice also draw their conclusions by asking honest questions born of genuine curiosity. There is no sense that the city mouse will move to the country, or that she will necessarily suffer some brutal fate as awaits so many characters on the wrong side of a lesson in Aesop’s fables. Rather, the two mice seem destined to live out their lives in their respective domains, each cherishing what they like about their own circumstance and eschewing the drawbacks of their cousin’s lifestyle. They are relatives and friends who respect one another even as they disagree with their opposite number’s decision. Despite the moral clearly taking sides, the story itself suggests that bygones can simply be bygones.

Three weeks from tomorrow, this nation of mice will scurry to the polling places. Most have only a hazy understanding of policy issues, and will instead pull the lever for candidates who best represent their “values” of honest, hardworking country life or tolerant progressive city life. There will be little or nothing in the way of mutual respect, of bygones being bygones. In this American moment, the rift is nearly complete, each nest of mice convinced the other is in league with the cats.

And perhaps, sadly, one of those nests is correct.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com