Hayley Phelan in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

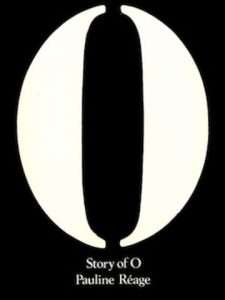

THERE HAS ALWAYS BEEN a lot of hand-wringing around erotica, especially erotica that centers on female submission. Feminists worry that it perpetuates harmful gender dynamics, while conservatives shudder at the frank depictions of female sexuality. Intellectuals usually dismiss it as smut. In the meantime, millions of people — mostly women — gobble it up. The box office success of Fifty Shades Freed, the third installment in the Hollywood trilogy based on E. L. James’s best-selling BDSM romance series, is only the latest example. How is it, wondered pundits, that this particular movie is a hit at the height of the #MeToo movement? Why are women flocking to see a film about a rich, white man dominating a much younger, much less powerful woman?

THERE HAS ALWAYS BEEN a lot of hand-wringing around erotica, especially erotica that centers on female submission. Feminists worry that it perpetuates harmful gender dynamics, while conservatives shudder at the frank depictions of female sexuality. Intellectuals usually dismiss it as smut. In the meantime, millions of people — mostly women — gobble it up. The box office success of Fifty Shades Freed, the third installment in the Hollywood trilogy based on E. L. James’s best-selling BDSM romance series, is only the latest example. How is it, wondered pundits, that this particular movie is a hit at the height of the #MeToo movement? Why are women flocking to see a film about a rich, white man dominating a much younger, much less powerful woman?

There’s no obvious reason that a movement against misogyny, sexual assault, and non-consensual advances should be incompatible with fantasies of consensual, sexual submission. For one thing, fantasies of submission are not strictly a female feminine phenomenon.

More here.

In a squalid, lawless “fugee” camp (the letters R and e have fallen off the entrance gate) that looks and smells like a giant Portaloo, one of the characters in Mohammed Hanif’s ambitious third novel considers running away to the desert. “What’s the worst that can happen,” he thinks. “I’ll starve to death. I’ll roast under the sun. God left this place a long time ago… He had had enough. I have had a bit more than that.” This philosophical passage is spoken by a dog called Mutt, and Hanif’s book is undoubtedly a high-wire act. Red Birds constantly threatens to fall apart, its characters and locations both achingly realistic and elusively metaphysical. But that’s part of its charm: you never know where Hanif’s farce will go next. He starts with an American pilot crashing in the desert near a downgraded refugee camp “full of human scum” he was supposed to bomb. When Major Ellie finally reaches the outskirts of the camp, Mutt introduces him to a teenage refugee named Momo, who is using an old copy of Fortune as his guide to becoming a hotshot businessman.

In a squalid, lawless “fugee” camp (the letters R and e have fallen off the entrance gate) that looks and smells like a giant Portaloo, one of the characters in Mohammed Hanif’s ambitious third novel considers running away to the desert. “What’s the worst that can happen,” he thinks. “I’ll starve to death. I’ll roast under the sun. God left this place a long time ago… He had had enough. I have had a bit more than that.” This philosophical passage is spoken by a dog called Mutt, and Hanif’s book is undoubtedly a high-wire act. Red Birds constantly threatens to fall apart, its characters and locations both achingly realistic and elusively metaphysical. But that’s part of its charm: you never know where Hanif’s farce will go next. He starts with an American pilot crashing in the desert near a downgraded refugee camp “full of human scum” he was supposed to bomb. When Major Ellie finally reaches the outskirts of the camp, Mutt introduces him to a teenage refugee named Momo, who is using an old copy of Fortune as his guide to becoming a hotshot businessman. Behaviorism, which flourished in the first half of the 20th century, is a school of thought in psychology that rejects the study of conscious experience in favor of objectively measurable events (such as responses to stimuli). Due to behaviorism’s influence, researchers interested in emotion in animals have tended to take one of two approaches. Some have treated emotion as a brain state that connects external stimuli with responses.7 These researchers, for the most part, viewed such brain states as operating without the necessity of conscious awareness (and therefore as separate from feelings), thus avoiding questions about consciousness in animals.8 Others argued, in the tradition of Darwin, that humans inherited emotional states of mind from animals, and that behavioral responses give evidence that these states of mind exist in animal brains.9 The first approach has practical advantages, since it focuses research on objective responses of the body and brain, but suffers from the fact that it ignores what most people would say is the essence of an emotion: the conscious feeling. The second approach puts feelings front and center, but is based on assumptions about mental states in animals that cannot easily be verified scientifically.

Behaviorism, which flourished in the first half of the 20th century, is a school of thought in psychology that rejects the study of conscious experience in favor of objectively measurable events (such as responses to stimuli). Due to behaviorism’s influence, researchers interested in emotion in animals have tended to take one of two approaches. Some have treated emotion as a brain state that connects external stimuli with responses.7 These researchers, for the most part, viewed such brain states as operating without the necessity of conscious awareness (and therefore as separate from feelings), thus avoiding questions about consciousness in animals.8 Others argued, in the tradition of Darwin, that humans inherited emotional states of mind from animals, and that behavioral responses give evidence that these states of mind exist in animal brains.9 The first approach has practical advantages, since it focuses research on objective responses of the body and brain, but suffers from the fact that it ignores what most people would say is the essence of an emotion: the conscious feeling. The second approach puts feelings front and center, but is based on assumptions about mental states in animals that cannot easily be verified scientifically.

In 2014, two archaeologists,

In 2014, two archaeologists,  It’s no secret that computers are insecure. Stories like the

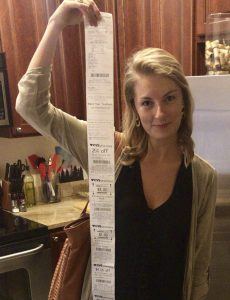

It’s no secret that computers are insecure. Stories like the  CVS is a drugstore much like other drugstores, with one important difference: The receipts are very long.

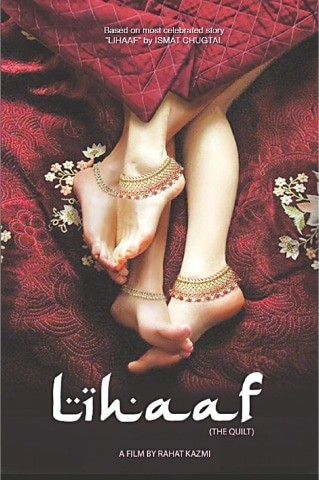

CVS is a drugstore much like other drugstores, with one important difference: The receipts are very long. A picture is worth a thousand words. In the case of Indian filmmaker (not to be confused with the Pakistani actor) Rahat Kazmi’s 2018 film Lihaaf: The Quilt, based on Ismat Chughtai’s controversial short story of the same name, the production’s publicity poster says perhaps more than a thousand words.

A picture is worth a thousand words. In the case of Indian filmmaker (not to be confused with the Pakistani actor) Rahat Kazmi’s 2018 film Lihaaf: The Quilt, based on Ismat Chughtai’s controversial short story of the same name, the production’s publicity poster says perhaps more than a thousand words. Somewhere in my parents’ photo albums there is a picture of me, aged seven or eight, lying in my bed, reading. On the wall, there are postcards from holidays, a poster of space pirate

Somewhere in my parents’ photo albums there is a picture of me, aged seven or eight, lying in my bed, reading. On the wall, there are postcards from holidays, a poster of space pirate  Last week Donna Strickland, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo, won the Nobel Prize in Physics. She is the third woman to be awarded the prize in its history—Marie Curie received it in 1903 and Maria Goeppert Mayer in 1963—but as recently as last May, Wikipedia rejected a draft page about Strickland on the grounds that she did not meet “notability guidelines.” The work for which she received the Nobel—generating the “shortest and most intense laser pulses ever created by mankind,” according to the prize committee—is over 30 years old. She published the groundbreaking paper, with co-authors and now co–Nobel winners Gerard Mourou and Arthur Ashkin, in 1985. Between then and now she has won many prizes, but it took a Nobel for her to become Wikipedia-worthy.

Last week Donna Strickland, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo, won the Nobel Prize in Physics. She is the third woman to be awarded the prize in its history—Marie Curie received it in 1903 and Maria Goeppert Mayer in 1963—but as recently as last May, Wikipedia rejected a draft page about Strickland on the grounds that she did not meet “notability guidelines.” The work for which she received the Nobel—generating the “shortest and most intense laser pulses ever created by mankind,” according to the prize committee—is over 30 years old. She published the groundbreaking paper, with co-authors and now co–Nobel winners Gerard Mourou and Arthur Ashkin, in 1985. Between then and now she has won many prizes, but it took a Nobel for her to become Wikipedia-worthy. A year ago, on a late afternoon in November, I decided to walk the seven miles from my hotel in Manhattan to Brooklyn’s Community Bookstore. It was a cool day, on the cusp of evening, at a moment when things, even grimy New York-type of things, seem to glow, and I was so busy looking around that I almost didn’t notice the small white sign that someone had placed at the bottom of Brooklyn Bridge. The green lettering was newly painted and read: ‘LIFE IS WORTH LIVING.’

A year ago, on a late afternoon in November, I decided to walk the seven miles from my hotel in Manhattan to Brooklyn’s Community Bookstore. It was a cool day, on the cusp of evening, at a moment when things, even grimy New York-type of things, seem to glow, and I was so busy looking around that I almost didn’t notice the small white sign that someone had placed at the bottom of Brooklyn Bridge. The green lettering was newly painted and read: ‘LIFE IS WORTH LIVING.’

Last month, Apple unveiled the latest version of its watch, featuring new health-monitoring features such as alerts for unusually low or high heart rates, and a way to sense when the wearer has fallen over and, if so, call the emergency services. In itself, that sounds pretty cool, and might even help save lives. But it’s also another nail in the coffin of social solidarity.

Last month, Apple unveiled the latest version of its watch, featuring new health-monitoring features such as alerts for unusually low or high heart rates, and a way to sense when the wearer has fallen over and, if so, call the emergency services. In itself, that sounds pretty cool, and might even help save lives. But it’s also another nail in the coffin of social solidarity.