by Robert Fay

I spent my freshman year at a drab suburban college pining for the cosmopolitan life of Boston. I whined and schemed and eventually engineered a transfer to Suffolk University in the city, where I was certain I’d meet fabulous Bohemian people who chain-smoked unfiltered Camels and read Rimbaud and William Blake by candlelight. Suffolk owned three Queen Anne revival buildings in the Back Bay and operated them as pseudo-rooming houses. I was 19 and had seemingly become an Emersonian self-actualized person overnight. I had propelled myself into the middle of a vibrant city, just two blocks from the upper-end of Newbury Street with Tower Records, the Avenue Victor Hugo book shop, the Trident Bookstore Café, Urban Outfitters (still indescribably outlaw in 1991) and Newbury Comics, the city’s punk rock record store.

I had arrived, or so it seemed, until I took stock of this new person and found he was remarkably unchanged, despite the sparkling offerings of the city.

Old problems persisted. The ground rules of interpersonal relations remained mysterious to me. I overshared with acquaintances and got clingy. Good people quickly fled, leaving me withdrawn and depressed, and vulnerable to centripetal forces within.

I desperately wanted to be loved by everyone—the consequences of a cold, unloving home I suppose—and I discovered people, particularly young women, had no patience for needy college sophomores.

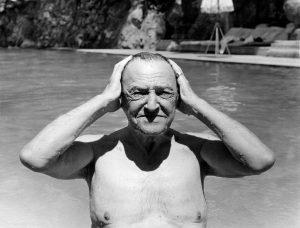

Yet that autumn was not without its pleasure. I still recall one glorious week—crimson and vermillion leaves swirling across Commonwealth Avenue—when I curled up in bed with a Signet Classic paperback of Of Human Bondage (1915) by Somerset Maugham. I read the book with teenage abandon. I identified completely with the club-footed Philip Carey and his masochistic attraction to the cruel and vacuous paramour Mildred Rogers, who cared nothing for him, and got her kicks toying with his lap-dog like attention.

Maugham’s narrator tell us, “(Philip) hated her. He knew he was a fool to bother about her; she was not the sort of woman who would ever care two straws for him, and she must look upon his deformity with distaste, he made up his mind that he would not go to tea that afternoon, but hating himself, he went.”

I was enthralled. Mr. Maugham had mapped the deepest depths of my particular human condition, and I in turn as his reader, I felt had glimpsed inside him as well.

In those pre-digital years, I knew nothing of Maugham’s biography except what I had read in the brief biographical note in the book. I didn’t know he was homosexual, had lost his parents at a young age and in the words of Christopher Hitchens, “was farmed out to mean relatives and cruel, monastic boarding schools. The traditional ration of bullying, beating, and buggery seems to have been unusually effective in his case, leaving him with a frightful lifelong speech impediment and a staunch commitment to homosexuality.”

*

Now that I’m middle-age, I find myself weary of readers wanting to “identify” with characters or to approach a novel as a vehicle for empathy-expansion. I read for intellectual stimulation, pleasure, the joy of navigating uncharted territory, but almost never for solace. Yet despite my vigilance—and almost against my will—I find myself occasionally ambushed by a sentence or a snippet of dialogue. It’s like turning the corner and glimpsing a beautiful woman—and you are disarmed, achingly vulnerable. The author has slipped off the authorial veil for a moment and I find myself receiving a message outside the premeditations of craft, plot and style—suddenly the author and I are both naked, and alone with one another.

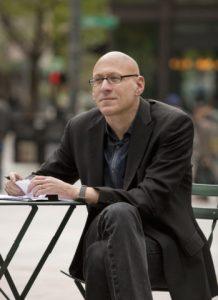

It happened recently while reading the new English translation of the novel The Females (2010), by the German writer Wolfgang Hilbig. The Females is centered in a universe not unlike that of Dostoevsky’s underground man, or better yet, the landscapes of Laszlo Krasznahorkai. The protagonist has been fired from his factory job. He lives in communist-ruled East Germany and must interview with a state magistrate to secure a new occupation. He is a failed writer of pornography who yearns for love from a mother and a state that is incapable of providing it. Holed up in his apartment, he is obsessing on his separateness from others, his alienation from “normal” people:

“Yet again it seemed possible that I could be one of them, that I could deceive them, that they could overlook my true condition. Yes, even overlook my boundless tension as I went into their midst, hoping to seem at least outwardly calm. That they wouldn’t sense how utterly ensnared I was by my anxious desire for people to like me. That I was completely dominated by this one craving to be loved, and at the same time extremely concerned to reveal that craving to them.”

Hilbig’s English translator Isabel Fargo Cole met the author in the 1990s and she remembers, “there was something unapproachable about him though he had a warm, avuncular aura. He had intense social anxiety and severe alcohol problems, especially toward the end of his life. In some sense he wasn’t of this world; even his closest friends felt they hardly knew him.”

The rest of the book does not betray Hilbig’s social anxiety or separateness in any explicit way. It is largely a surreal book with stylized prose and big ideas, where the author remains hidden behind the machinations of the artist. But for a brief moment, I found Hilbig, and in a way, he found me too.

*

Moments of authorial vulnerability are not be confused with autobiographical fiction, or even the “write what you know” mantra of American creative writing programs. Mr. Tolstoy’s battle scenes in War and Peace, for example, are as detailed and as riveting as his St. Petersburg soirees. This is in part because Tolstoy knew both worlds intimately—he was a combat veteran of the Crimean War and a titled gentlemen, Count Leo Tolstoy—and, even more importantly, he was a genius.

Try as I might, I cannot find Tolstoy the man in any of his great works, for the genius-artist rules every comma and every conjunction. Looking for the finite person named Leo in Anna Karenina or War and Peace is like trying to find God in the beauty of a wind-swept forest—one can certainly believe he is present—but all you get are gusts, leaves and swaying trunks.

The same is true of the books of Jane Austen, William Faulkner, Evelyn Waugh and Ernest Hemingway. In their great books, we certainly find reflections of their religious beliefs, regional affiliations, social backgrounds, etc., but do we really glimpse the 61-year-old man who shot himself in an Idaho cornfield with a shotgun?

If we fast forward several decades and consider another American novelist who took his life, David Foster Wallace, it becomes easier to find the person in the prose. From the recent DFW biography by D.T. Max, Every Love Story is Ghost Story (2012) we know that during Wallace’s days as a graduate student at Harvard, he had suicidal feelings and was addicted to alcohol and marijuana. He was admitted to the famed McClean Hospital in Massachusetts for rehab, the same institution where literary icons Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath had gone for their own psychiatric reboots.

And though Wallace never revealed any of this publicly, the author’s mental struggle is found in passages of Infinite Jest (1996), particularly via the minor character of Ken Erdedy, the cannabinoid addict who bunkers himself in his Boston apartment anxiously waiting on his pot dealer. Erdedy is locked within the downward spiral of obsessive, self-doubting, hyper-self-conscious thoughts familiar to anyone who has suffered from depression or anxiety. As Erdedy waits, he becomes more anxious his dealer won’t come. He considers whether to call her, but checks himself, noting that calling is precisely what a creepy, obsessive drug-addicted person might do:

“He had this thing where he’d frequently say he was getting dope mostly for friends. Then if the woman didn’t have it when she said she’d have it for him and he became anxious about it he could tell the woman that it was his friends who were becoming anxious, and he was sorry to bother the woman about something so casual but his friends were anxious and bothering him about it and he just wanted to know what you could maybe tell them. He was caught in the middle, is how he could represent it…thinking back he was sure he’d said whatever, which in retrospect worries him because it might have sounded as if he didn’t care at all, not at all, so little that it wouldn’t matter if she forgot to get it or call, and once he’d made the decision to have marijuana in his home one more time it mattered a lot. It mattered a lot. ”

*

You could argue that examining the distinction between the author and the person is now an irrelevant exercise. The future will likely have far less “once upon a time” works of fiction and far more books that are a hybrid form of narrative nonfiction, history, fiction, memoir, literary criticism and personal essay. Books like W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (1992) and Ben Lerner’s 10:04 (2014) are cases in point, or even Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015), which is a fascinating blend of memoir and academic inquiry that manages to be both personally revelatory and intellectually substantial. The question of Maggie Nelson hiding or not hiding behind an authorial veil is moot here. The book establishes an immediate pact with the reader that what you read herein, will be frank and deeply personal, such as:

“Sometimes when I’m teaching, when I interject a comment without anyone calling on me, without caring that I just spoke a moment before, or when I interrupt someone to redirect the conversation away from an eddy I personally find fruitless. I feel high on the knowledge that I can talk as much as I want to, in any direction that I want to, without anyone overtly rolling their eyes at me, or suggesting I go to speech therapy. I’m not saying this is good pedagogy. I’m saying that its pleasures are deep.”

The last two sentences are pitch-perfect, honest—the kinds of things we feel but rarely admit—and representative of the kind of thoughtful self-examination that is woven into the book.

Some of this ground has already been examined by David Shields in his manifesto Reality Hunger (2010). He makes the case for the irrelevancy of unselfconscious literary fiction in favor of new forms that incorporate journalism, memoir, history—whatever—and result in new works of literature. I’m an admirer of Shields’ book, but I take issue with the assertions: “Every man’s work—whether it be literature or music or pictures or architecture or anything else—is always a portrait of himself,” or more succinctly, “Every sound we make is a bit of autobiography.”

This is true, no doubt, of average-to-good artists. But who really cares about them? Why should I concern myself with averageness, particularly when it comes to art? We can accept average co-workers and middling brothers-in-laws, but life is too short for “good” novelists. Give me genius or give me death.

Shields is arguing that writers should dispense with the tired conceits of the 19th Century novel and write more transparently, accept they’re writing about the life around them, own it, and experiment with new forms of narrative non-fiction and memoir. Shields believes the success of reality television is an indicator of our need for “the real.” And if the events of September 11th taught us anything, it’s that reality is always operating beyond the limits of our imaginations. In other words, don’t discount reality, it’s likely a richer vein than something artfully constructed.

Yet the great artists, the immortals, don’t actually work on the plane of the real or even the personal. They are the mythmakers, the one’s who raise their hands to the sky and summon muses and goddesses and shocks of lightening. They can slip free from the limitations of personal experience and speak for the universal human story. And we’re not just talking Cervantes or Homer or Shakespeare. Flannery O’Conner stories, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1923) and Philip Roth’s American Pastoral (1998) are not examples of literary fiction, but mythological tales that will certainly outlast American civilization.

I’m undecided whether Maugham’s novels will be judged by history as immortal works. But he communed with my younger self at a critical time, and truthfully, his words have always had more impact on me than Tolstoy’s.

So poor Philip will remain with me. I won’t soon forget him or Maugham for that metter. I can still picture Philip in the streets of Edwardian London trying, pathetically, to get the most basic concessions from a woman who is spitefully indifferent. “It’s very hard when you’re as much in love as I am,” Philip says to Mildred. “Have mercy on me. I don’t mind that you don’t care for me. After all you can’t help it. I only want you to let me love you.”

Robert Fay’s essays, reviews and stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Millions, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly Review, among others. Follow him on Twitter @RobertFay1.