Robert Butler in MIL:

IF THERE WERE to be a statue outside the BBC’s new offices in central London that captured the spirit of its modish interior of “workstation clusters”, “back-to-back booths” and “touchdown areas”, and the daily struggle of the 5,500 employees to produce content across multiple platforms for an audience of 240m, it might be that of the anxious, well-fed, middle-aged, middle-class white male, with a lanyard dangling over his hi-vis jacket, who is running late for his meeting and struggling to fold his Brompton bicycle. That would be Ian Fletcher, the over-stretched head of values (played by Hugh Bonneville) and central character in “W1A”, the BBC’s sprightly satire about itself. But Fletcher is not the one who will be on the plinth outside Broadcasting House. In 2016 a statue of George Orwell—paid for by Michael Frayn, Tom Stoppard, David Hare and Rowan Atkinson among others—will be unveiled, a few yards beyond the outdoor ping-pong table.

IF THERE WERE to be a statue outside the BBC’s new offices in central London that captured the spirit of its modish interior of “workstation clusters”, “back-to-back booths” and “touchdown areas”, and the daily struggle of the 5,500 employees to produce content across multiple platforms for an audience of 240m, it might be that of the anxious, well-fed, middle-aged, middle-class white male, with a lanyard dangling over his hi-vis jacket, who is running late for his meeting and struggling to fold his Brompton bicycle. That would be Ian Fletcher, the over-stretched head of values (played by Hugh Bonneville) and central character in “W1A”, the BBC’s sprightly satire about itself. But Fletcher is not the one who will be on the plinth outside Broadcasting House. In 2016 a statue of George Orwell—paid for by Michael Frayn, Tom Stoppard, David Hare and Rowan Atkinson among others—will be unveiled, a few yards beyond the outdoor ping-pong table.

Orwell spent a mere two years (1941-43) at the BBC, which he joined as a talks assistant in the Indian section of the Eastern Service. No recording survives of him giving a talk, which is perhaps fitting; for what is most striking about his essays and journalism is the tart, compelling timbre of his voice. The critic Cyril Connolly, an exact contemporary, thought that only D.H. Lawrence rivalled Orwell in the degree to which his personality “shines out in everything he said or wrote”. Any reader of Orwell’s non-fiction will pick up on the brisk, buttonholing manner (“two things are immediately obvious”), the ear-catching assertions (“the Great War…could never have happened if tinned food had not been invented”) and the squashing epithets: “miry”, “odious”, “squalid”, “hideous”, “mealy-mouthed”, “beastly”, “boneless”, “fetid” and—a term he could have applied to himself—“frowsy”.

Orwell might well have damned this new honour too. In his studio on the edge of the Blenheim estate in Oxfordshire, Martin Jennings, the sculptor working on the eight-foot likeness, told me that Orwell had made some disobliging remarks about public statues, thinking that they got in the way of perfectly good views. The bronze Orwell will look down on the comings and goings of BBC staff who, returning his gaze, can read some chiselled wisdom from his works on the wall behind him. The Financial Times recently called Orwell “the true patron saint of our profession”, another tribute he would probably resist. “Saints”, he warned, “should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent.”

More here.

In the rendering, the structure looks like an enormous golden wave, spilling from the Upper Esplanade of Melbourne’s St Kilda Beach, crossing a busy road and crashing onto the sand. In reality, it would be a canopy of nearly 9,000 flexible photovoltaic panels designed to connect a shopping and entertainment district with the beach while generating renewable energy. Called “Light Up,” the proposal is the winner of a contest sponsored by the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), an

In the rendering, the structure looks like an enormous golden wave, spilling from the Upper Esplanade of Melbourne’s St Kilda Beach, crossing a busy road and crashing onto the sand. In reality, it would be a canopy of nearly 9,000 flexible photovoltaic panels designed to connect a shopping and entertainment district with the beach while generating renewable energy. Called “Light Up,” the proposal is the winner of a contest sponsored by the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), an  May 1968 marked the political awakening of my generation. I was a junior at the American College for Girls in Istanbul at the time, feeling the revolutionary winds as a young Jewish woman in a predominantly Muslim society and because of the anti-Americanism precipitated by the Vietnam War. Pictures of napalm attacks on Vietnamese children and adults circulated among us during lunch hours. And when the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet scheduled a visit to Istanbul, and many boyfriends, relatives, and others were clubbed by the police, our sense of political disappointment with and opposition to U.S. policies increased.

May 1968 marked the political awakening of my generation. I was a junior at the American College for Girls in Istanbul at the time, feeling the revolutionary winds as a young Jewish woman in a predominantly Muslim society and because of the anti-Americanism precipitated by the Vietnam War. Pictures of napalm attacks on Vietnamese children and adults circulated among us during lunch hours. And when the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet scheduled a visit to Istanbul, and many boyfriends, relatives, and others were clubbed by the police, our sense of political disappointment with and opposition to U.S. policies increased. A landmark report from the United Nations’ scientific panel on climate change paints a far more dire picture of the immediate consequences of climate change than previously thought and says that avoiding the damage requires transforming the world economy at a speed and scale that has “no documented historic precedent.”

A landmark report from the United Nations’ scientific panel on climate change paints a far more dire picture of the immediate consequences of climate change than previously thought and says that avoiding the damage requires transforming the world economy at a speed and scale that has “no documented historic precedent.” ‘Now Greece can finally turn the page in a crisis that has lasted too long. The worst is over.’ With these triumphant words, Pierre Moscovici, the EU Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, declared an end to the EU’s eight-year €289 billion bailout programme to Greece, the largest rescue in financial history.

‘Now Greece can finally turn the page in a crisis that has lasted too long. The worst is over.’ With these triumphant words, Pierre Moscovici, the EU Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, declared an end to the EU’s eight-year €289 billion bailout programme to Greece, the largest rescue in financial history. After decades of attention to Oscar Wilde’s 1895 trials and his incarnation of the homosexual subject, a spate of recent publications reconsiders his 1882 American lecture tour, among them David Friedman’s Wilde in America (2014), Roy Morris Jr’s Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America (2013), and Sharon Marcus’s “Salomé!! Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde, and the Drama of Celebrity” (2011). Editors Matthew Hofer and Gary Scharnhorst set the stage for this reappraisal by assembling the first complete and reliable record of Wilde’s interviews in Oscar Wilde in America: The Interviews (2010). While these publications illuminate Wilde’s redefinition of Victorian masculinity, they also highlight his self-promotion, burgeoning celebrity, and vending of aestheticism before he became a gay icon. To this compendium, Michèle Mendelssohn adds an exciting new chapter, or one so old that it deserves fresh examination. She ponders coverage of the Irish aesthete Wilde, which harmonised with racist caricatures of black dandies in American minstrel shows and newspapers. Back in 1882, Lloyd Lewis and Henry Justin Smith’s Oscar Wilde Discovers America offered a whistle stop account of Wilde’s tour replete with historical magazine illustrations, reviews, and gossip, which frequently conflated aestheticism with race matters. A juxtaposition that seemed unremarkable and inoffensive in 1882 receives extensive scholarly elaboration in Mendelssohn’s fascinating book.

After decades of attention to Oscar Wilde’s 1895 trials and his incarnation of the homosexual subject, a spate of recent publications reconsiders his 1882 American lecture tour, among them David Friedman’s Wilde in America (2014), Roy Morris Jr’s Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America (2013), and Sharon Marcus’s “Salomé!! Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde, and the Drama of Celebrity” (2011). Editors Matthew Hofer and Gary Scharnhorst set the stage for this reappraisal by assembling the first complete and reliable record of Wilde’s interviews in Oscar Wilde in America: The Interviews (2010). While these publications illuminate Wilde’s redefinition of Victorian masculinity, they also highlight his self-promotion, burgeoning celebrity, and vending of aestheticism before he became a gay icon. To this compendium, Michèle Mendelssohn adds an exciting new chapter, or one so old that it deserves fresh examination. She ponders coverage of the Irish aesthete Wilde, which harmonised with racist caricatures of black dandies in American minstrel shows and newspapers. Back in 1882, Lloyd Lewis and Henry Justin Smith’s Oscar Wilde Discovers America offered a whistle stop account of Wilde’s tour replete with historical magazine illustrations, reviews, and gossip, which frequently conflated aestheticism with race matters. A juxtaposition that seemed unremarkable and inoffensive in 1882 receives extensive scholarly elaboration in Mendelssohn’s fascinating book. “I was born in the wrong century”, the London-based Mexican novelist Chloe Aridjis announces near the beginning of Female Human Animal. Josh Appignanesi’s new film is a knowing blend of the assured and the amateurish which understands its place in cinema history, and consequently has a lot of fun playing around in it. The times are soulless Aridjis declares, quoting her idol,

“I was born in the wrong century”, the London-based Mexican novelist Chloe Aridjis announces near the beginning of Female Human Animal. Josh Appignanesi’s new film is a knowing blend of the assured and the amateurish which understands its place in cinema history, and consequently has a lot of fun playing around in it. The times are soulless Aridjis declares, quoting her idol,  T

T IN JANUARY, the critic and novelist Francine Prose took to Facebook to express her outrage at a short story in the latest issue of The New Yorker by a relatively unknown writer named Sadia Shepard. Second-guessing The New Yorker’s fiction department is something of a parlor game among members of the literati, but Prose wasn’t interested in quibbling over aesthetics. To her, the story, titled “

IN JANUARY, the critic and novelist Francine Prose took to Facebook to express her outrage at a short story in the latest issue of The New Yorker by a relatively unknown writer named Sadia Shepard. Second-guessing The New Yorker’s fiction department is something of a parlor game among members of the literati, but Prose wasn’t interested in quibbling over aesthetics. To her, the story, titled “ 6.6 million — that’s how many spots on the human genome Sekar Kathiresan looks at to calculate a person’s risk of developing coronary artery disease. Kathiresan has found that combinations of single DNA-letter differences from person to person in these select locations could help to predict whether someone will succumb to one of the leading causes of death worldwide. It’s anyone’s guess what the majority of those As, Cs, Ts and Gs are doing. Nevertheless, Kathiresan says, “you can stratify people into clear trajectories for heart attack, based on something you have fixed from birth”. Kathiresan, a geneticist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, isn’t alone in counting outrageously high numbers of variants. The polygenic risk scores he has developed are part of a cutting-edge approach in the hunt for the genetic contributors to common diseases. Over the past two decades, researchers have struggled to account for the heritability of conditions including heart disease, diabetes and schizophrenia. Polygenic scores add together the small — sometimes infinitesimal — contributions of tens to millions of spots on the genome, to create some of the most powerful genetic diagnostics to date. This approach has taken off thanks to a number of well-resourced cohort studies and large data repositories, such as the UK Biobank (see pages

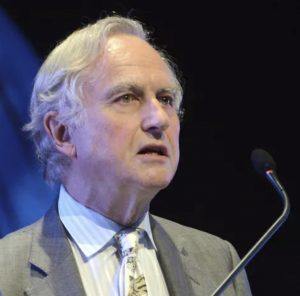

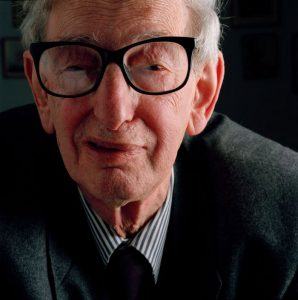

6.6 million — that’s how many spots on the human genome Sekar Kathiresan looks at to calculate a person’s risk of developing coronary artery disease. Kathiresan has found that combinations of single DNA-letter differences from person to person in these select locations could help to predict whether someone will succumb to one of the leading causes of death worldwide. It’s anyone’s guess what the majority of those As, Cs, Ts and Gs are doing. Nevertheless, Kathiresan says, “you can stratify people into clear trajectories for heart attack, based on something you have fixed from birth”. Kathiresan, a geneticist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, isn’t alone in counting outrageously high numbers of variants. The polygenic risk scores he has developed are part of a cutting-edge approach in the hunt for the genetic contributors to common diseases. Over the past two decades, researchers have struggled to account for the heritability of conditions including heart disease, diabetes and schizophrenia. Polygenic scores add together the small — sometimes infinitesimal — contributions of tens to millions of spots on the genome, to create some of the most powerful genetic diagnostics to date. This approach has taken off thanks to a number of well-resourced cohort studies and large data repositories, such as the UK Biobank (see pages  Many atheists think that their atheism is the product of rational thinking. They use arguments such as “I don’t believe in God, I believe in science” to explain that evidence and logic, rather than supernatural belief and dogma, underpin their thinking. But just because you believe in evidence-based, scientific research – which is subject to strict checks and procedures – doesn’t mean that your mind works in the same way.

Many atheists think that their atheism is the product of rational thinking. They use arguments such as “I don’t believe in God, I believe in science” to explain that evidence and logic, rather than supernatural belief and dogma, underpin their thinking. But just because you believe in evidence-based, scientific research – which is subject to strict checks and procedures – doesn’t mean that your mind works in the same way. Imagine throwing a baseball and not being able to tell exactly where it’ll go, despite your ability to throw accurately. Say that you are able to predict only that it will end up, with equal probability, in the mitt of one of five catchers. The baseball randomly materialises in one catcher’s mitt, while the others come up empty. And before it’s caught, you cannot talk of the baseball being real – for it has no deterministic trajectory from thrower to catcher. Until it becomes ‘real’, the ball can potentially appear in any one of the five mitts. This might seem bizarre, but the subatomic world studied by quantum physicists behaves in this counterintuitive way.

Imagine throwing a baseball and not being able to tell exactly where it’ll go, despite your ability to throw accurately. Say that you are able to predict only that it will end up, with equal probability, in the mitt of one of five catchers. The baseball randomly materialises in one catcher’s mitt, while the others come up empty. And before it’s caught, you cannot talk of the baseball being real – for it has no deterministic trajectory from thrower to catcher. Until it becomes ‘real’, the ball can potentially appear in any one of the five mitts. This might seem bizarre, but the subatomic world studied by quantum physicists behaves in this counterintuitive way. Good news and bad news arrived this week

Good news and bad news arrived this week  At the risk of not sounding patriotic, as I grew older, I came into some conflict with the aesthetic of Trinidadian jazz.

At the risk of not sounding patriotic, as I grew older, I came into some conflict with the aesthetic of Trinidadian jazz. Prepare to grapple with the cosmic grandiosity and optical hot-messes of that 19th-century French freak of painterly nature, Eugène Delacroix, who’s churning, turgid, crimson-tinged floridity has enkindled the respiratory systems of artists since he first debuted at the Paris Salon of 1822 — and given many others agita.

Prepare to grapple with the cosmic grandiosity and optical hot-messes of that 19th-century French freak of painterly nature, Eugène Delacroix, who’s churning, turgid, crimson-tinged floridity has enkindled the respiratory systems of artists since he first debuted at the Paris Salon of 1822 — and given many others agita. In several respects, John Wray’s “

In several respects, John Wray’s “ Almost all Marxists have imagined themselves to be part of a global community. More than perhaps any other modern ideology, Marxism has given its adherents a sense of being connected across regions, countries and continents. The activists, thinkers, politicians, students, workers, guerrilla fighters and party apparatchiks who, throughout the 20th century, claimed Marxist ideals for themselves rarely agreed on what Marxism was or where it was headed. But they knew that they were not alone. At its height, Marxism created a web of interconnected communities at least as powerful as the Muslim ummah, complete with its own heretics, infidels, rogue saviours and clerics.

Almost all Marxists have imagined themselves to be part of a global community. More than perhaps any other modern ideology, Marxism has given its adherents a sense of being connected across regions, countries and continents. The activists, thinkers, politicians, students, workers, guerrilla fighters and party apparatchiks who, throughout the 20th century, claimed Marxist ideals for themselves rarely agreed on what Marxism was or where it was headed. But they knew that they were not alone. At its height, Marxism created a web of interconnected communities at least as powerful as the Muslim ummah, complete with its own heretics, infidels, rogue saviours and clerics.