by Robert Fay

I spent my freshman year at a drab suburban college pining for the cosmopolitan life of Boston. I whined and schemed and eventually engineered a transfer to Suffolk University in the city, where I was certain I’d meet fabulous Bohemian people who chain-smoked unfiltered Camels and read Rimbaud and William Blake by candlelight. Suffolk owned three Queen Anne revival buildings in the Back Bay and operated them as pseudo-rooming houses. I was 19 and had seemingly become an Emersonian self-actualized person overnight. I had propelled myself into the middle of a vibrant city, just two blocks from the upper-end of Newbury Street with Tower Records, the Avenue Victor Hugo book shop, the Trident Bookstore Café, Urban Outfitters (still indescribably outlaw in 1991) and Newbury Comics, the city’s punk rock record store.

I had arrived, or so it seemed, until I took stock of this new person and found he was remarkably unchanged, despite the sparkling offerings of the city.

Old problems persisted. The ground rules of interpersonal relations remained mysterious to me. I overshared with acquaintances and got clingy. Good people quickly fled, leaving me withdrawn and depressed, and vulnerable to centripetal forces within.

I desperately wanted to be loved by everyone—the consequences of a cold, unloving home I suppose—and I discovered people, particularly young women, had no patience for needy college sophomores.

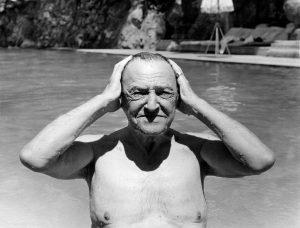

Yet that autumn was not without its pleasure. I still recall one glorious week—crimson and vermillion leaves swirling across Commonwealth Avenue—when I curled up in bed with a Signet Classic paperback of Of Human Bondage (1915) by Somerset Maugham. I read the book with teenage abandon. I identified completely with the club-footed Philip Carey and his masochistic attraction to the cruel and vacuous paramour Mildred Rogers, who cared nothing for him, and got her kicks toying with his lap-dog like attention. Read more »