by Priya Malhotra

“How are you?” asked my aunt about a year ago in my living room in New Delhi, her tone languorous and inquisitive, her gaze perched on my face. Having recently moved back to India after about 28 years in the U.S., this deceptively simple question both thrilled and discomfited me. I was used to being in the U.S. where people routinely asked, “How’re you doin’?”—a greeting that always put me on the defensive. I’d always try to justify my existence by magnifying whatever I was doing with my life at that moment and try to make it sound important. That day, just as I’d grown accustomed to doing in the U.S., I rattled off the things I was doing to my aunt, which, at the time, weren’t a whole lot. I was visiting my ailing mother in the hospital, reorganizing things in the house, and getting in touch with friends. There was a great deal of leisure at that time, I must admit. (I can feel my stomach muscles contract as I write this—I feel guilty confessing to indulging in leisure. I feel I must legitimize my leisure time, make it sound somehow “earned.” See how conditioned I am?)

My aunt furrowed her eyebrows, confusion washing over her face as she said, “Priya, I didn’t ask you what you were doing. I wanted to know how you are.” And then I spilled out all my feelings about my mother’s illness, my move to India, and my various conundrums. At that time, I also began thinking about how much language reveals about a culture, and how everyday expressions in American English signify America’s devout veneration of action, motion, and productivity.

Besides “how’re you doing?,” there are numerous expressions in American English that reflect this obsession with action and ceaseless motion, this deeply ingrained notion that the value of doing vastly supersedes the value of being. “What’s happening?” “What are you doing this weekend?” “What are your plans for the summer?” The underlying implication is always the same—are you active enough to matter? Are you doing enough to validate your existence? (When I lived in the U.S., the pressure to do sometimes became so overwhelming for me that I started conjuring up grand plans for the weekend. Instead of admitting that I intended simply to veg out in bed and watch some Netflix, I’d say things like I was planning to see an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Friday, listen to a fabulous new jazz sensation in the West Village on Saturday, followed by dinner at a cozy Peruvian restaurant.)

Now back to language. What’s one of the first questions people ask each other when they first meet in America? Read more »

“In bardo again,” I text a friend, meaning I’m at the Dallas airport, en route to JFK. I can’t remember now who came up with it first, but it fits. Neither of us are even Buddhist, yet we are Buddhist-adjacent, that in-between place. Though purgatories are not just in-between places, but also places in themselves.

“In bardo again,” I text a friend, meaning I’m at the Dallas airport, en route to JFK. I can’t remember now who came up with it first, but it fits. Neither of us are even Buddhist, yet we are Buddhist-adjacent, that in-between place. Though purgatories are not just in-between places, but also places in themselves.

Do corporations have free will? Do they have legal and moral responsibility for their actions?

Do corporations have free will? Do they have legal and moral responsibility for their actions?

Stephanie Morisette. Hybrid Drone/Bird, 2024.

Stephanie Morisette. Hybrid Drone/Bird, 2024.

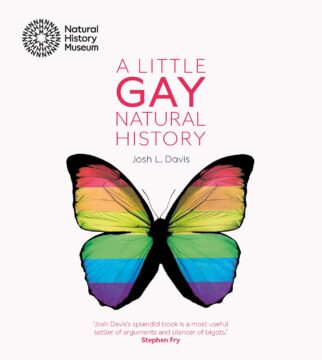

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.

If you had to design the perfect neighbor to the United States, it would be hard to do better than Canada. Canadians speak the same language, subscribe to the ideals of democracy and human rights, have been good trading partners, and almost always support us on the international stage. Watching our foolish president try to destroy that relationship has been embarrassing and maddening. In case you’ve entirely tuned out the news—and I wouldn’t blame you if you have—Trump has threatened to make Canada the 51st state and took to calling Prime Minister Trudeau, Governor Trudeau.