by Adele A.Wilby

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

In his inaugural speech on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump jumped into the fray on the contentious issues of gender identity and sex when he announced that his administration would recognise “only two genders – male and female”. At this point there is no conceptual clarity on his understanding of the contested issues of ‘gender’ and ‘male and female’, but we do not have to wait too long before he clarifies his position. His executive order, ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremists and Restoring Biological Truth to Federal Government’ signed by him soon after the official formalities of his inauguration were completed, sets out the official working definitions to be implemented under his administration.

Trump issuing orders for ‘defending women’ would have undoubtedly raised the hackles of many and sniggers from even a greater number of women who are only too aware of his derogatory comments about women and his questionable and contested long history of relationships with them, but that is not the issue here. What is at issue is the clarification the executive order expounds on his conceptual understanding of sex when it says, “Sex’ shall refer to an individual’s immutable biological classification as either male or female. “Sex” is not a synonym for and does not include the concept of gender identity’. This delinking of sex and gender allows space for gender diversity, but that is a short-lived optimism. The executive order continues to elaborate the gender essentialist view that ‘women are biologically female, and men are biologically male’. In other words, he denies the fluidity of gender identity and the diversity of cultural constructions of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ and posits gender as inextricably linked to biology.

The gender concepts of ‘woman’ and ‘man’ remain unclarified in the text, but by grounding these identities in biology, the executive order, in one sweep, rejects the cultural constructions of gender and delegitimises the identity of transgender persons or any other gender identity an individual might feel and experience themselves to be.

A plethora of literature exists to challenge these gender essentialist categories in the executive order. Indeed, my own research focused on how the military transforms ‘women’ into soldiers, modelled on the image of a ‘man’, ‘masculinity’ or ‘military masculinity’. One of my many findings was the diversity and complexity of identities of military women throughout history and how they shift from social ideas of femininity as caring, kind and less violent to one of military masculinity that allows them to perform military roles in frontline war contexts.

Essentialising gender identity in biology embeds gender within the realm of nature, it is ‘natural’ and there is an assumption that gender and human reproductive behaviour will flow ‘naturally’, and heteronormative relationships and off-spring will be the outcome. But can this confidence in nature delivering the expected heteronormative individual be justified? Scientists are increasingly revealing this ‘immutable biological classification’ of male and female is also not without controversy. When we delve into the world of nature, as the executive order does, we observe a staggering number of animals, plants and fungi that defy the binary of male and female as ‘natural’. The extra-ordinary examples of sexual diversity compel us to question any underlying assumptions we might have about the ‘naturalness’ of heteronormativity.

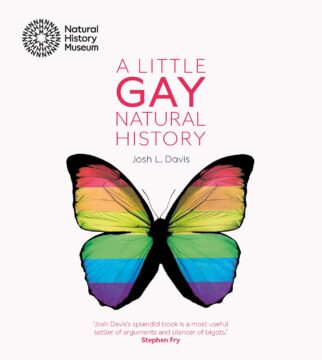

Josh Davis’s recently published A Little Gay Natural History reveals to us the complexity of sex and sexual behaviour in the animal world. A science writer at the Natural History Museum in London, Davis writes from a background in biology and conservation.

This book is small, but it is well researched, drawing on an extensive literature from different sciences to present highly accessible, succinct information of the astonishing diversity of sex and sex behaviour amongst animals, plants, insects and fungi. Coloured photographs of the species he presents compliment the information he provides and contributes towards making this book an informative and interesting read.

The diversity of animals, plants and fungi on the planet never ceases to amaze, but not only do these species look different but they also behave and live differently, and one of the aspects of this diverse life is their sex and sexual behaviours. Davis adopts a workable definition for sex, when he says it is, ‘defined by the size of the sex cell produced by the individual’, This means that ‘’female’ is used to refer to the individuals of a species that typically produce larger sex cells, while ‘male’ is used to refer to those that typically produce smaller sex cells’, a more specific definition than that which appears in Trump’s executive order. Davis, and others, also reveal that , ‘sex itself is also not that straightforward, as it can be dependent on a number of different characteristics, including but not limited to genetics, hormones and anatomy, and it is a spectrum rather than a clear cut category’.

Davis shies away from engaging in the complex issue of gender identity, especially when it comes to animals, but this is not a flaw in the book. He rightly comments, ‘it is impossible to ask other lifeforms if they are actually gay, lesbian, bisexual or queer’. Instead, when expanding on the sex behaviour in the animal world he opts for ‘the term ‘gay’ to refer to male-male behaviours, ‘lesbian’ when talking of female-female behaviours, ‘homosexual’ when referring to either ‘queer’ as something of an umbrella term when talking about more general non-heteronormative behaviours, but not necessarily related to sexual behaviour alone’. Davis also makes clear that his book ‘is not a comprehensive list of queer behaviours and identities, and it is not making analogies between what is seen in nature and the human race’ (italics added).

Having clarified his working definitions and objectives, Davis then proceeds with his examples and takes us into a wonderful, confounding world of diverse sexual behaviours by species from across the entire biological tree. Homosexual behaviour, Davis reveals, is just one form of sexual behaviour in the animal world. According to Davis, the quoted number of known species that exhibit some form of homosexual behaviour is around 1500, and this could be an underestimate. He further asserts, ‘the most obvious assumption is that most species of animal probably exhibit some form of queer behaviour, and being a purely heterosexual species is the exception’. That the ‘purely heterosexual species is the exception’ is quite a statement that would probably invite a critical response from many sources but given the number of species on the planet and the frequency of different forms of sexual behaviours, it is surely not outside the realm of possibility.

Nevertheless, he begins with the relatively well-known sexual activity of the Adéline penguins. Dr George Murray Levick, a doctor on board an expedition to Antarctica in 1917, lived amongst the Adéline penguins for three months and was able to observe the full breeding season, scrupulously recording their behaviour. From his notes, it appears looks can be deceiving: these sweet, gentle looking birds involve in unexpected, sometimes aggressive, sexual behaviours which includes males ‘engaging in necrophilia with dead females, forced copulations and gay sex’. A surprised Levick observed a ‘cock copulating with a hen. When he had finished… the apparent hen turned out to be a cock, and the action was performed with their positions reversed, the original ‘hen’ climbing on to the back of the original cock’. Gorillas across the central tropical belt of Africa also engage in queer behaviours. Within bachelor groups, according to Davis, gorillas form a complex network of homosexual pairings. Bonobos also involve in ‘a lot of sex’ and display possibly the largest repertoire of homosexual behaviour amongst the animals. Males and females of all ages involve in oral sex, masturbation, sex and even kissing with tongues, sexual behaviour that to the human species will be familiar. Females establish intense female relationships with ‘genital-genital’ rubbing. How often also have we all looked at sheep grazing leisurely in the field with the assumption that they just get on with ‘normal’ procreation between a ewe and a ram. Alas. According to Davis, studies show that ‘roughly 8% of all rams show a consistent preference for other rams…’ despite ewes being in oestrus and veterinarians injecting the rams to boost their ‘low libido’.

But although the male and female biological cells are fundamental to reproduction, that the cells exist in two distinct life forms, as Davis shows, is not always consistent. ‘Parthenogenesis’ is a process where a species has done away with sexual reproduction but nevertheless lay fertile eggs without ever encountering sperm; it is all down to the genetics of the creature, and the whiptail lizards are an example of this. Another anomaly is the sexually dimorphic species that change sex. In a fascinating example of sex diversity, most parrot fish change sex from female to male when they reach a certain age, with a few shifting from male to female. Known as sequential hermaphrodites, they produce both male and female sex cells but at different points in their life. ‘Protogynous’ parrot fish start out as female and change to male as they grow larger. In ‘protandry’ they shift from male to female. And then there is the species where sex determination is dependent on the temperature, and an example of this is the green sea turtle. These turtles nest on sandy beaches, and for the incubating eggs the temperature of 29°C is ideal, but lower temperatures will produce males and higher temperatures favour females.

The book includes a fascinating array of diverse examples of homosexual behaviour from giraffes, swans, the common cockroach; of environmentally dependent sex determination found in the European eel; of female led societies such as hyenas whose genitals are almost indistinguishable from the males; of fungi that produce numerous sexes, to name a few.

Davis’s book introduces a wondrous world of sexual diversity and behaviour amongst nature that is a fascinating read and excites an interest to delve deeper into that complex world. But importantly, given the complexity of sex and sexual behaviours amongst nature, the book encourages reflection on attitudes to different sexual behaviours amongst human beings also. Can we anticipate therefore, a future when all the moral angst about sexual behaviour in human beings will become an issue of the past, and we will acknowledge that sex and gender diversity amongst human beings is as much a part of our species as that of other animals we share the planet with? In such an eventuality, divisive dictates on sex and gender identity in presidential executive orders will surely be a thing of the past and dumped in the dustbin of history.