by David Kordahl

Twenty years after Steven Pinker argued that statistical generalizations fail at the individual level, our digital lives have become so thoroughly tracked that his defense of individuality faces a new crisis.

When I first picked up The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Steven Pinker, 2002), I was in my early twenties. The book was nearly a decade old, by then, but many of its arguments were new to me—arguments that, by now, I have seen thousands of times online, usually in much dumber forms.

In The Blank Slate, Pinker argued that humans are wired by evolution to make generalizations. These generalizations often lead us to recognize statistical differences among human subgroups—average variations between men and women, say, or among various races. Pinker showed that these population-level observations—these stereotypes—are often surprisingly accurate. This contradicted the widespread presumption at the time that stereotypes must be avoided mainly due to their inaccuracy. Instead, Pinker suggested that stereotypes often identify group tendencies correctly, but fail when applied to individuals. The argument against stereotyping, then, should be ethical rather than statistical, since any individual may happen not to mirror the groups that they represent.

Midway through reading The Blank Slate, I went to the theater to watch Up in the Air (2009), in which George Clooney portrayed a Gen-X corporate shark. At one point, Clooney advised his horrified Millennial coworker to follow Asians in lines at airports. “I’m like my mother,” he quipped. “I stereotype. It’s faster.”

This got a big laugh. We didn’t know, then, that Clooney—with his efficiently amoral approach to human sorting—represented our own algorithmic future.

Life in 2010 was still basically offline. But as members of my generation moved every aspect of our lives onto the servers, it became steadily easier to identify individuals by their various data tags. Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking) (Christian Rudder, 2014) was assembled by one of the co-founders of the dating website OkCupid. It generalized wildly about differences among various racial groups, but no one could accuse the book of simple racism. Tech founders, after all, have large-number statistics to back up their claims—the very patterns that Pinker suggested were natural for humans to perceive, now amplified by enormous datasets and the sophisticated tools of data science. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self portrait with Shutter and Tree, Merida, March 2025.

Sughra Raza. Self portrait with Shutter and Tree, Merida, March 2025.

If there is one commonly held “truth” that governs conventional wisdom about wine tasting, it is that wine tasting is thoroughly subjective. We all have different preferences, unique wine tasting histories, and different sensory thresholds for detecting aromatic compounds. One person’s scintillating Burgundian Pinot Noir is another person’s thin, weedy plonk. But this “truth” is at best an oversimplification; like a very good Pinot Noir, matters are more complex.

If there is one commonly held “truth” that governs conventional wisdom about wine tasting, it is that wine tasting is thoroughly subjective. We all have different preferences, unique wine tasting histories, and different sensory thresholds for detecting aromatic compounds. One person’s scintillating Burgundian Pinot Noir is another person’s thin, weedy plonk. But this “truth” is at best an oversimplification; like a very good Pinot Noir, matters are more complex.

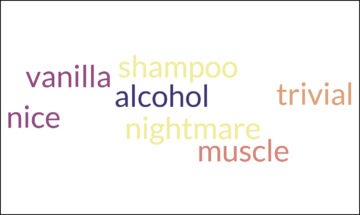

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?