by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

1. Roses

1. Roses

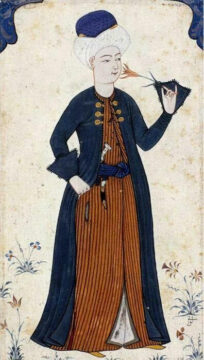

Miniatures and illuminated manuscripts from the Islamic world offer up an abundance of floral depictions. Cultivating gardens and replicating them in art, has a spiritual dimension, as gardens symbolize paradise; “Jannah” in the Qur’an is a “hidden garden” that inspires to be revealed and realized in the creative arts. Gardens have a place in the realm of earthly power too; from Spain to India, some of the most elaborate garden designs were commissioned under Muslim rule. In portraits of princes and noblemen, there is often a sprig of flowers or a single rose in one hand, slightly raised, whereas the body is angled to show the regalia: jewels, sashes and belts with daggers or swords. While a flower in bloom in an imperial image may symbolize vitality, refinement, and a concern for balancing the fierce with the tender, the true poignancy it evokes lies in its vulnerability and inevitable decline.

A famed ghazal verse captures a most spectacular swing of empire’s pendulum: the end of one of the wealthiest and culturally most opulent empires in history, the Mughal empire, whose dominion over large swathes of territory in South Asia was wrested from it by the British Raj. As he lies dying in exile (1862), the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar writes:

How hapless is Zafar, for his burial

Not even two yards of land could be found in the beloved’s neighborhood

Some of his most finely wrought poems are in the Sufi vein, exquisite verses that stand apart in the Urdu cannon. I would if I could, bring roses as homage to his resting place, left unmarked, in Burma where he died.

While the king yearns for two yards of burial ground in the land his ancestors ruled over with such pomp for centuries, the British Empire, though destined to be short-lived, is fast expanding, and by the nineteenth century, comprises nearly one-quarter of the world’s land surface.

Its collapse notwithstanding, the splendor of the Mughal empire leaves a mark on the Western imagination. “In Milton’s Paradise Lost,” Historian William Dalrymple writes in The New York Review, “the great bustling Mughal cities are revealed to Adam after the Fall as future wonders of God’s creation. To a man of Milton’s generation, this was no understatement, for Lahore dwarfed any city in the West: “The city is second to none, either in Asia or in Europe,” thought the Portuguese Jesuit Father Antonio Monserrate, “with regard to size, population, and wealth. It is crowded with merchants, who foregather there from all over Asia…. There is no art or craft useful to human life which is not practiced there…. The citadel alone…has a circumference of nearly three miles. From the ramparts of that citadel—the Lahore fort—Akbar ruled over most of India, all of what is now Pakistan and Bangladesh, and much of Afghanistan. For their impoverished contemporaries in the West, the Mughals became symbols of luxury and might—attributes with which the word “mogul” is still loaded.”

2. Saddles and Scarves

It is 1837. Moguls are rising from unexpected places, luxury is about to be redefined as global brands. The last Mughal, king only in name, Bahadur Shah’s coronation too is nominal; father’s prized crown, royal decorum, but only a few besides the family who are present at the ceremony. The pall of an all but fallen empire hangs. Real power lies with the British East India Company. Not only are empires of the East succumbing to the West, the textbook of empire is being written anew. It is the year two companies bound to become icons of the elite, Hermès and Tiffany, happen to come into existence.

Thierry Hermès launches a business selling handcrafted equestrian outfitting that soon transforms into a luxury fashion house with an allure so great, the company need not have a marketing department. While the royalty and aristocracy once commissioned ateliers and stylists that were out of reach for commoners, a culture of exclusive fashion now welcomes anyone who has the money, regardless of social status or cultural background. In other words, social standing is, for the first time, no longer a matter of lineage but is possible to curate, as long as the exorbitant price tags are met.

As merchants of luxury leather goods, from saddles and gear for carriages, to bags and the first golf jacket with a zipper, to perfumes and iconic silk scarves popularized by Queen Elizabeth herself, the house of Hermes becomes a tastemaker and attracts all manner of moneyed people, keeping prices and demand high, and supply low, maintaining exclusivity.

After centuries of trade in commodities that are newfound luxuries in Europe— spices, silk, finespun cotton, carpets, sugar, tea— Britain and France move on from establishing economic clout through claiming control over the yields and use of colonized land and water, exploiting human capital in the form of slavery and military, to negotiating cultural power as well.

Authors supporting empire, such as Kipling, make a perverted case for war and colonization as a gesture of benevolence in domesticating the savage, who is “the white man’s burden.”

In a time when human values are under discussion as a reason to do away with antiquated power structures such as empires of the East, human values at home are rearranged. Writers and poets— Thomas Hardy, Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, among them— respond to the tensions between the social strata, and the oppressive, suffocating work conditions that ordinary people endure as they contend with the effects of the Industrial revolution. Many nineteenth century poets, artists and composers in Europe engage with the aesthetic language of the colonized cultures, mostly with the Orientalist sensibility, but a few make a serious study out of the centuries-old tradition of Islamic arts with a goal of making it their own— one of the most prominent and successful among them is artist and textile designer William Morris who is greatly influenced by Islamic design, its geometric grammar, color palette and interpretation of nature, especially vegetal and floral patterns. The floral wallpapers that Morris designs for Morris & Co, go on to become luxury items, icons of Victorian English sophistication, with an unmistakable influence of the classic Islamic garden. In an imperial culture so fixated on the material and earthly that places of control such as China and Cashmere are synonymous with objects of luxury (even as their inhabitants are degraded), Morris’s embrace of the sacred language of flowers, as rendered in Islamic geometric patterns, offers a new take on Jannah, the garden of heavenly prize. The final homage from an artist fighting to balance the spirit with art and commerce, comes when the fabric of his design “Granada,” based on the Ottoman tulip motif and metal thread with gold-wrapped wefts, is chosen as the pall for his coffin.

3. Perfume:

What “opens like a flower” with a “stench was so strong, that you might think/To swoon away upon the grass,” is the beloved’s body in Charles Baudelaire’s poem “The Carcass.” She goes “beneath the grasses and fat flowers,/Moldering amongst the bones,” eaten with kisses by vermin.

If the imagery of graphic decay makes your stomach turn, it is intended to have that effect. Baudelaire’s Epicurean aesthetic calls for embracing degeneracy; in his view, the artist stands apart from the common herd, a self-styled figure, aloof from the tide of democracy and so-called human values.

In 1857, Baudelaire publishes Les Fleurs du mal (“The Flowers of Evil”), a work at the forefront of the Decadent movement. As Hermes designs bags and jackets ordinary people can only dream of owning, art movements such as Decadence, reinforce the idea of excess as a form of catharsis, a celebration of ego; it serves to elevate the self, even in the perverse. The truth in Shakespeare’s “That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet,” is no longer a truism. Social bonds are being called into question, and while there is a healthy assessment of aesthetic norms, there is also a preoccupation with excess and ego; the “odor of dead roses,” in the words of the Irish novelist, George Moore, prevails.

Nearly a hundred years later, in 1951, the first perfume created by Hermès, Eau d’Hermès, is launched. Inspired by the smell of a luxurious Hermès leather bag, mixing notes of leather with citrus and spices from the East for which land was stolen and wars waged by Western colonizers— those notes of cumin, cinnamon, and sandalwood.

In 1857, after an attempt of resistance by sympathizers of the Mughals is met with a bloodbath by the British masters, India officially capitulates. Mirza Ghalib, one of the greatest poets of all time, who once kept company with the emperor Bahadur Shah himself, writes in his letters about the despair and destruction of Delhi in the chokehold of the Raj, the terror and destitution.

A master of the lyric, with a penchant for philosophic compression, his verse on reflections within reflections, though not addressing Empire, nonetheless bears commentary on its spectacle in which we are made to be spectators of a scene that includes us. Hope comes from being watched by a greater entity, the Divine, or the One who manifests hope in mirrored reflections that multiply.

In the words of scholar Mehr Afshan Farooqi: “In this verse, Ġhālib has crafted a unique image of illusions. Gardens with mirror-flowers means an illusory garden, signifying that there are illusions within illusions. A subtle irony is at play here. ‘Mirror-flower’ may mean ‘the mirror which is like a flower’, or it may mean ‘a mirror in which a flower is reflected.’”

Chaman chaman gul-i-ainah dar kinar-i-havas

Umeed-i-mahv-i-tamasha-i-gulsitan tujh se

There is an abundance of mirror-flowers in desire’s embrace/ Hope is a spectator engrossed in the colorful garden, because of You

4. Mirror:

Be it the reflective windows of Rodeo Drive, the Champs Elysses, or the polished marble of the cultural heart of Dubai which mostly comprises shopping malls where coveted luxury brands are sold, the face in the mirror is the subject of Capitalism, its cog, its bot, unwitting or unwilling ally. The manufacture of desire, once relayed via magazines, and commercials, is now on a screen in the palm of the hand, an endless loop. Without the consumer, without you and I, there is no market, without the market, there is no Empire.

In 1943, after looting and exploiting Mughal India the “crown jewel,” the British orchestrate a famine in Bengal under Churchill’s orders who famously calls Indians a “beastly people.” Rudyard Kipling calls the native Pathans and Afghans “visages of weasels and swine” in his article in The Civil and Military Gazette. A hundred years later, it is Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who refers to Palestinians as “human animals,” repeatedly declaring that he will “finish them” in this “war of civilization,” “a war not just for Israel’s survival but of the entire civilized community,” “all civilized people.” “You know deep down that Israel is fighting your fight.” The lies and delusions of empire become weaker and more transparent.

It is October of 2025, the Empire has been viewed naked by the world, in its machinations, fraud, and malevolence, as it fully funds and supports the genocide of the Palestinian people. The graphic witness of the ongoing horrors perpetrated by Israel has written its indelible history. Where colonialism functions on the theft of language, it has failed in the case where live footage of unspeakable atrocities is accessed by all and sundry, around the globe. And yet, every hour, more Palestinians are being slaughtered or starved to death. The empire’s mirror is swallowing the victim and the witness. The role of art is to create a mirror larger than empire, to seize delusion and set us free. I recall this poem by Mahmoud Darwish, written in 1995:

Our star will hang up mirrors.

Where should we go after the last frontiers?

Where should the birds fly after the last sky?

Where should the plants sleep after the last breath of air?

We will write our names with scarlet steam.

We will cut off the hand of the song to be finished by our flesh.

We will die here, here in the last passage.

Here and here our blood will plant its olive tree.