by Rafaël Newman

On Yom Kippur this year, I went to church.

On Yom Kippur this year, I went to church.

I hadn’t intended to go; or rather, I hadn’t noticed that the Jewish Day of Atonement would coincide with the date of the performance I had been planning to attend, and which was to be held in a church. I had realized just two days earlier that the Übersetzeressen (“Translators’ Dinner”), to which my employer had invited all of us in Languages Services, would by chance fall on September 30, International Translation Day, which is also the feast day of St. Jerome, the patron saint of translators. And so, heartened by this serendipity, I started investigating the significance of other dates during the same period, and came across Yom Kippur, which began this year at sundown on Wednesday, October 1, just as I was settling into my pew at the Reformierte Kirche Russikon for Winterreise.

Anna Gitschthaler, an Austrian soprano based in Switzerland, has thrillingly reconceived Franz Schubert’s song cycle as theater and has been performing it this month, together with pianist Rebecca Ineichen, director Adela Maria Bireich, and set designers Erika Gedeon & Stefan Schmidhofer, in Zurich’s Oberland. Gitschthaler is of course not the first to give Winterreise a dramaturgical makeover, nor is she the first female singer to perform the 1827 setting of 24 poems by Wilhelm Müller, conventionally sung by a man: I have written here about some innovative stagings, by Ian Bostridge, Brigitte Fassbaender, and Joyce DiDonato, as well as about my own involvement in a “gender-bending” performance of the cycle two years ago, with my colleagues Annina Haug and Edward Rushton. But Gitschthaler’s Winterreise is indeed a pioneering production—of Müller and Schubert’s evocation of suffering and redemption, as well as in its own right—because it makes self-conscious use of the sacral space of a temple as the (literal) staging ground for a work of musical theater, and thus innovatively enacts the equivalence of art and religion, if not in fact the superiority of the former over the latter.

I watched another artist of my acquaintance accomplish something similar this past summer. From January to October this year, as part of a program known as Arche 2.0, a large replica of an ark was installed in the Wasserkirche, a functioning protestant church that occupies the site of the martyrdom of Zurich’s patron saints and is adjoined to the Helmhaus, the city’s art exhibition space. During those months, in a year in which the city and its churches have been marking the 500th anniversary of Zwingli’s translation of the Bible, the ark served as the stage for a variety of events; the one I attended was by Nora Gomringer, a German-Swiss poet who assembled a collage of texts, by herself and others, concerning the Biblical flood and its literary and political echoes, including Europe’s ongoing treatment of would-be crossers of the Mediterranean, and performed it accompanied by percussionist Philipp Scholz.

But whereas Gomringer and Scholz presented their religiously inflected work in a church that had deliberately denatured itself, while maintaining a patent reference to one of its own foundational stories, Gitschthaler and her company made the temple strange on their own, with their set-designing choices and, above all, with the profoundly secular work they chose. The audience sat in the nave, while the stage occupied the chancel, across which sheets of bluish scrim had been spread to suggest snow drifts; a barren winter landscape was sketched in with a skeletal tree on which crow-like figures perched.

When Gitschthaler on occasion turned her back to us and approached the apse, the semicircular area at the end of the church lent her voice a ghostly echo and rendered the sacred space at once palpably present, and sacrilegiously transfigured: since Müller’s texts, which address loss, despair, and suicide, and at one climactic point propose a Nietzschean self-apotheosis in the absence of divinity, are the very antithesis of a Christian mass.

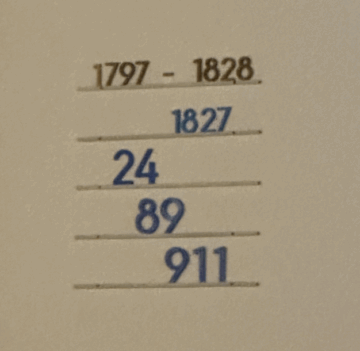

Gitschthaler’s perhaps most radical appropriation of the church as performance space, however, occurred obliquely, in a discrete paratextual gesture. To the left of the chancel, on the wall serving as a proscenium, she and her troupe had taken over the rails on which the numbers of the hymns to be sung by the congregation are displayed during a typical mass. Now, instead of references to the hymnals available in the backs of the pews, the audience could read Schubert’s dates (1797-1828), the year in which Winterreise had been composed (1827), the number of Lieder in the cycle (24), its opus number (89), and the catalogue number assigned it in 1951 by musicologist Otto Erich Deutsch (911).

With her overt privileging of the literary over the liturgical, Gitschthaler thus made manifest the waning of religion and its replacement by lyric poetry in the modern era, as noted by the German philosopher-poet Margarete Susman as early as 1910, and celebrated by Stefan George, the guru-like leader of a semi-mystical “circle” of poet-adepts in the first decades of the 20th century.

At the same time, I was also reminded of the performative nature of religion itself—all the more so because I was attending a secular theatrical event on Erev Yom Kippur, the eve of Judaism’s holiest holiday, in a protestant church, which double estrangement served to evacuate the occasion of any particular confessional allegiance and reduce the religious gesture to its degree zero: a sequence of ritualistic formulas. On Yom Kippur, ten days after Rosh Hashanah, Jews are called upon to prepare themselves for the New Year by renouncing any vows or pledges they may have rashly made during the year past. Kol Nidre, the famous chant recited at evening service by the synagogue cantor, is in effect a legal speech act, the subject’s formal unbinding from obligations unthinkingly entered into, which it would otherwise be bound to uphold. The ancient Aramaic formula kol nidre means “all vows,” and the cantor performs their dissolution on behalf of the congregation:

All vows, and prohibitions, and oaths, and consecrations … that we may vow, or swear, or consecrate, or prohibit upon ourselves… Regarding all of them, we repudiate them. All of them are undone, abandoned, cancelled, null and void, not in force, and not in effect. Our vows are no longer vows, and our prohibitions are no longer prohibitions, and our oaths are no longer oaths.

Whether the practice arose from the need for Jews to foreswear their forced conversion, or out of an abundance of caution in the face of the magically binding power of words, Kol Nidre makes for impressive theater. Many years ago, when my elder daughter was around five, I decided that I would expose her to the traditions of her paternal great-grandparents. I took her with me when I accompanied Jewish friends on Erev Yom Kippur to the Löwenstrasse Shul in Zurich, where we had been living for the past few years.

The synagogue is orthodox—like my grandparents—which meant that women were seated in the gallery, while men congregated on the ground floor of the building, directly before the bima, or officiant’s stage, with the ark of the covenant. My friends and I thus split into two groups at the door: I entrusted my daughter to the women among us, who took her upstairs with them, while I joined the men downstairs as the service began.

It wasn’t long, however, before I heard my daughter’s little voice, rising slowly in panic above me—and it was no surprise, for the performance being enacted on the bima was a genuinely frightening piece of theater. Several of the male congregants had assembled onstage, where, wrapped head to foot in their prayer shawls, which gave them the appearance of corpses in their winding sheets, they were swaying back and forth as they mournfully recited the text of Kol Nidre along with the cantor. I was finally obliged to escort my terrified daughter, who had been handed back to me on the staircase by one of my female friends, out of the synagogue, and home to our secular habitat.

What I was left with (apart from a mildly traumatized five-year-old) was the realization that religion isn’t always religious, at least not in the conventional, Christian sense of a gratifying communion with the supernatural and a promise of otherworldly redemption designed to distract from the depredations of life on earth. And I was reminded of a possible etymology of the word “religion,” which may be derived from the Latin for “binding” or “obligation,” and which by such interpretation is in fact adequately applied to Kol Nidre: a legal pronouncement made without mention of any deity in recognition of the binding power of human speech, and the public performance of the subject’s autonomous unbinding from obligations arising from that same power.

Religion as ethics: or rather, ethics—a code of conduct in communal human affairs—codified as what we have come to call religion, but which, in our increasingly secular world, might better (and more hopefully) be termed politics. As Friedrich Engels wrote about the German Peasants’ War, it is misleading to view the violent confrontations of farmers and noblemen during the 16th century as the mere by-product of an obscure theological dispute initiated by Martin Luther, and not as a political challenge to a murderously oppressive social hierarchy carried out in the only theoretical terms available to contemporaries: class struggle couched as millenarian revival.

By this same token, Kol Nidre can be seen as the public acknowledgment, enacted within the sanctifying framework of a temple, of the crucial fact that human vows need not be eternally binding, but can also be unbound by humans themselves. Or, in Brecht’s words, Wer a sagt, der muß nicht b sagen. Er kann auch erkennen, daß a falsch war—“You are not obliged to follow on automatically from your first premise: you can also recognize that your first premise was wrong.”

We are currently seeing too little of this sort of contemplation on the part of political actors, in particular those who profess the Jewish faith in what they regard as the Jewish homeland: by failing to review their initial vows of revenge and retaliation, or indeed by failing to publicly recognize that those vows were specious, merely the cover for a self-serving political agenda, they are thus betraying the ethical spirit of the Jewish High Holiday just past.

Corey Robin, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College and a prominent Jewish advocate of a just peace in the Middle East, has recently written:

Kant becomes the first hero of modern philosophy by saying that Abraham was wrong, that, as Abraham himself realized in the prior story of Sodom and Gomorrah, there is something higher than God, which is justice itself, and that what justice, with its concomitant idea of humanity requires of us, is not obedience but disobedience, that in the face of injustice, we never in fact have the right to obey, but only the duty to disobey, even if we are disobeying God. Because, again, justice is higher. That’s what grounds the monotheistic turn of Abraham, not a particularistic story of the Jews, but the universal story of disobedience to the highest authority, even if that authority is God, in the name of something greater, namely, justice.

It is in the name of such justice, and with my sense of the religious revitalized by a secular performance in a sacred space, that I revile and renounce the hideous, genocidal war crimes being perpetrated by the IDF at the behest of Netanyahu’s loathsome government; and, at the same time, that I also dedicate these reflections on religion, performance, and the political to the memory of those murdered in Manchester on Yom Kippur 2025.