by Ada Bronowski

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the breezy weightless of: ‘La vie ne vaut rien, rien, … rien ne vaut la vie’ (life is worth nothing, nothing, …nothing is worth life’, here). The song is finesse incarnate if that already is not too much of an oxymoron since finesse is anything but carnal. The rich assonances of the refrain where ‘rien’ (nothing) rimes with ‘tiens’ (I hold) and echoes with ‘seins’ (breasts) lift the contradiction, making the breasts abstract and life concrete. The second, flippancy, is the sand British humour was built on from Bertie Wooster to Black Adder (was, alas, as David Stubbs shows in his recent Different Times: A History of British Comedy, that flippant British humour is now dead after Boris Johnson chose to do politics rather than comedy). It is the lightness that transforms despair into melancholy, the weight of the world on one’s shoulders into elegance and panache.

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the breezy weightless of: ‘La vie ne vaut rien, rien, … rien ne vaut la vie’ (life is worth nothing, nothing, …nothing is worth life’, here). The song is finesse incarnate if that already is not too much of an oxymoron since finesse is anything but carnal. The rich assonances of the refrain where ‘rien’ (nothing) rimes with ‘tiens’ (I hold) and echoes with ‘seins’ (breasts) lift the contradiction, making the breasts abstract and life concrete. The second, flippancy, is the sand British humour was built on from Bertie Wooster to Black Adder (was, alas, as David Stubbs shows in his recent Different Times: A History of British Comedy, that flippant British humour is now dead after Boris Johnson chose to do politics rather than comedy). It is the lightness that transforms despair into melancholy, the weight of the world on one’s shoulders into elegance and panache.

The third F is at the root of all lightness. Fantasy, etymologically, comes from the Greek word for light, phos – a word which already in antiquity contains the double-usage echoed in our English ‘lightness’: the shining light and what is detached from the heaviness of anchors. Fantasy is the realm of the light in all its senses. It is what the light shows us: surfaces, glimmers and shimmers which we can never quite be sure are true, nor can we positively dismiss as false. It is the realm of an in-between that we cannot not wish that it could be real.

Surely if we can see it, it must be real?

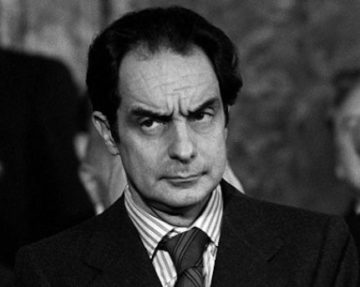

Even when we know – or we come to know – that it is not, it cannot be real, we can never quite shake off the allure of fantasy. What if? is a question that accompanies every waking hour of ours, consciously or unconsciously – it is what we also call hope. Literature and the arts at large take over not from disappointment at reality but from a sense, more or less explicit depending on our character, that hope is real just not for us right now. Fantasy is the realisation of the lightness we cannot give up on even when – especially when – the weight of reality crushes us. Italo Calvino, who would be a hundred and one day old today, in the first of his Six Memos for the Next Millenium (1988) traces the lineage of lightness from Roman poet Lucretius who sees wars, love and volcanoes as mere assemblies of atoms floating in the void, to Florentine Renaissance poet Guido Cavalcanti whom Boccacio portrays, in one of the novellas of his Decameron, as a dreamy outsider. Cavalcanti, cornered against the wall of the cemetery by the riotous youth of the town, ‘because he was so light’ jumps over the wall and escapes. That dancer’s jump, over tombs and death, crystallises a poetic vision of the power of the ‘spirits’ in us – the spiritello which is a Cavalcanti mascot. In a famous sonnet, Pe’ gli occhi fere un spirito sottile, (Through the eyes, a subtle spirit strikes…), the sweet little spirit of love (spiritello) holds the key to all other spirits that move us towards one another especially towards the one we love. Spirit is everywhere, body is nowhere, and in this absence, love has the swiftest of motions; it dashes through the purity of the air, of the snow, of running water.

Cavalcanti’s is the poetry of the non-impediment of weight as fact, not fiction. And that is where Calvino places fantasy. Shakespeare is there as well with his Puck and his Ariel, Cyrano de Bergerac, the 17th century writer and adventurer who wrote The Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1657) is there too with his schemes to fly to the moon on the back of the exhalations of the dew; Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837) as well, who is so in love with the moon that he sublimates language, not to write a paean to the moon, but, as Calvino puts it, ‘to remove from language every heaviness, so as to make language sound like light’ – the light that comes from the moon.

Fantasy is not a literary genre in itself – or was not before Netflix and co. – but rather the invention of the means of getting away from the heaviness of our bodies. It is as such, first and foremost a philosophical conundrum, explained by the first philosopher of fantasy, that is to say, of the thwarted desire for the reality of appearances and the horror of the heavy, Plato. If Plato warns us so forcefully about the illusory lure of surface images and unfounded desires for them (even when we know full well it cannot be so), it is because he himself is well acquainted with the temptation. The temptation to take what we know is weightless, (the image in the mirror, our dreams, the characters in a play), to be real, to not be weightless, to have a body so that we can seize it. He is a master fantasist precisely because he never ceases from one dialogue to the other to play out the crisis of desire and repulsion for lightness.

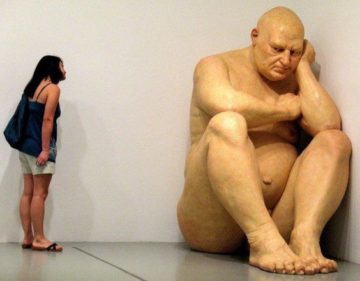

He is a master fantasist not because, like Homer, he invented wonderful monsters. Sure, thanks to Plato, alongside the cyclops or the lotus eaters, we are to this day captivated by the horrific sounding four-armed, four-legged monsters who invented love the day they were cut in two to become the humans we are, doomed to roam the earth in search of our beloved other halves. But already the philosophers in antiquity noted that such inventions have more to do with the mechanics of logical thinking than abandonment to images. What we call science-fiction, the Greeks would call logic: ‘by analogy and by way of enlargement, we get giants, by way of subtraction, we get one-eyed giants, by way of combination, we think of hybrid beasts with four arms.’[1] The logicians on and around Plato’s day regimented the creation of monsters. But what Plato did was far greater and deeper than logic: oh to get rid of the body!.. but not my body, nor yours, nor his nor hers…not a body, but the body. That is the craving, and there lies the rub for however much we wish it, not only is it not possible, but we also run the risk of not being around to enjoy the levity. For if death is the separation of the soul from the body, where does the soul go without a body? I can’t live with the body, I can’t live without a body, is Plato’s U2 remake.

The ordeal of the slave, who escapes the cave in Plato’s Republic’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’, is constituted by pain and physical effort, bolstered by incessant study and racking of the brain. All this contributes to the slave’s becoming weightless so as to leave the cave and find the light. All the while, Plato insists that such a man, the philosopher, does not exist amongst us. Such lightness is impossible because it would imply leaving the body behind, and a philosopher, i.e. an ascetic erudite visionary with the courage of a lone hero and the endurance of a mythical animal, cannot do all that without a body though the body is what impedes him from realising his goal. The impossible lightness of philosophy can only lead to death. And indeed, in Plato’s dialogue set at the very last hour of Socrates’ life, the Phaedo, in which we witness again and again each time we read it, the execution by hemlock of Socrates, with the minute description of Socrates’ feet getting cold and heavy first then his belly, his friends insist that this is the only and last philosopher alive who is now no more. For it is a contradiction of the laws of gravity to reach the lightness the true philosopher must reach to be free of the weight of his body – and still be here to philosophise. But in the dialogue, Socrates is serene and content because he will finally get rid of his body! As such, the Phaedo is the first work of fantasy of the Western canon, a work on the obsession for weightlessness and the demented conviction that it can be reached.

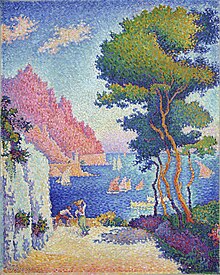

Calvino sees Lucretius as a point of origin of lightness in literature. There is something paradoxically true in that. For Lucretius, though fiercely anti-Plato, realises the Platonic dream of weightlessness, by doing away with the soul. In its stead: the void. Lucretius paints the Nature of Things as worlds (ours and the infinite other possible worlds) as atomised landscapes in which what we interpret in our heavy, serious ways as events, accidents and tragedies (but also passionate love affairs) are nothing but temporary meetings of infinitely small bits of floating matter. He invents Pointillism, centuries before Paul Signac (1863-1935) – Pointillism for philosophers, filling the world, filling bodies with void. The more bodies are filled with void, the more everything begins to float. What happens when we float?

Enter Calvino as author, and no longer critic. He is the anti-Kundera of late 20th century literature. Milan Kundera scrutinises mercilessly the unbearable lightness of being, that is to say, in fact, the inescapable weight of everything; that all the light and lightness we think we perceive turns out to be only more constricting heaviness we add to our lives. What seems to shine and glimmer is mere fantasy, in its most merciless dimension, that is, when we take appearances to be real and are doomed to disappointment at best, and more likely, as in Kundera’s novel, to be painfully punished for the mirage. Calvino is the opposite. Just as he pairs the opposing couple, Cavalcanti against Dante, Calvino and Kundera are an opposing couple too. Dante who sees lightness as vain metaphor that takes us up when first we must go down (to hell, etc.), Dante who gives vice and virtue their true weight in an epic anti-fantasist vision of our lives, Dante is the opposite of Cavalcanti’s abstractions about the spirit of love that sublimates bodies; Cavalcanti would never put Francesca and Paolo in hell. Calvino and Kundera are the Cavalcanti versus Dante of post-war modernism. Both reach out to an idea of lightness, the first to embrace it and rise towards it, in the wake of Cavalcanti, Cyrano and even, with his haunting irony, Kafka, the second, Kundera, to squeeze out all the air from the illusion of lightness and demonstrate its vanity.

Calvino’s lightness, his art of fantasy, is anything but escapism. His lightness is a principle of life, it orders the moral compass of his frail but backboned heroes: to elude the force of gravity at all costs. This is the moral imperative that drives the lives of the Calvinian hero/anti-hero.

Today, not only because of wars and terror attacks suffocating our everyday lives, but also because everyday social communication is so immune to irony, is so desultorily serious and heavy lest one cause offense, Calvino’s lightness, his philosophically-charged stories on living light are crucial, a last resort if not already inaudible. His works are one of the last bastions of human dignity – the dignity that is contained within the three F’s, flippancy, finesse and fantasy. It is a dignity which is emblematically portrayed by the titled heroes of his Trilogy of Our Ancestors, three novels in which a Baron, who decides to live in the trees and never set foot on the ground all his life, a Viscount, whose body is severed in two, one good, one bad, both parts wandering the earth separately until they reunite, and a Knight, who thought he existed only to discover he does not, represent the enduring tradition of ancestral nobility which reinvents itself through individual conquests of humanism. They each let themselves float, away from traditions, rules and institutions, and from the void that they find, they construct a personality that is whole because autonomous and self-reflecting.

Calvino’s lightness, his philosophically-charged stories on living light are crucial, a last resort if not already inaudible. His works are one of the last bastions of human dignity – the dignity that is contained within the three F’s, flippancy, finesse and fantasy. It is a dignity which is emblematically portrayed by the titled heroes of his Trilogy of Our Ancestors, three novels in which a Baron, who decides to live in the trees and never set foot on the ground all his life, a Viscount, whose body is severed in two, one good, one bad, both parts wandering the earth separately until they reunite, and a Knight, who thought he existed only to discover he does not, represent the enduring tradition of ancestral nobility which reinvents itself through individual conquests of humanism. They each let themselves float, away from traditions, rules and institutions, and from the void that they find, they construct a personality that is whole because autonomous and self-reflecting.

This reinvention of themselves takes place through an abandonment of weight: in The Cloven Viscount (1952), two halves of a man live, each, their separate lives. Each half is substantially less burdened: the good half free from the bad half, and the bad half from the good half. This unexpected lightness deepens their experience so that when after almost killing one another in a fight, they are finally reunited, the Viscount, whole again, is wise from these experiences and able to lead a happy life. The Viscount is the opposite of the lovesick humans Plato described in his myth of the origin of love mentioned earlier: the severance, there, is the cause of eternal unrest and damning incompleteness that weighs us yearning humans down for ever. For Calvino the severance is the unleashing of spirit in Cavalcanti’s sense, the possibility of finding oneself and a meaning for one’s life thanks to a rediscovered lightness.

In The Baron in the Trees (1957), a boy rebels against his authoritarian father and decides to live in the trees. He does so until old age, when, frail and more weightless than ever he jumps onto a flying balloon which disappears over the sea and the Baron with it. From his tree-top domain, the Baron, not only lives a full life filled with books, love and a constant confirmation of freedom, he also has the distance to think about social reform and the happiness of all, he writes a treatise which he sends to his contemporary the French philosopher Denis Diderot on how to build a new republic in the trees. Once everyone will be in the trees, he the Baron, will be able to go back down to the ground. Life in the trees yields a story which is in the image of the leaves at the tree-tops, little blots of colour – little atoms – surrounded by void. That void is the ‘internal enemy’ as Calvino himself writes in the introduction to the edition of the complete trilogy in 1960, which the heroes of his novels must not so much overcome but learn to live with. Live life as if it were a piece of embroidery… the last hero of the trilogy, the non-existent Knight represents the failure to do so, since he ends up dissolving into thin air when he finds he has nothing, neither duty, nor purpose, to live for. The heroes of the Trilogy are thus all concerned with giving life to the sense of incompleteness and void within, not defying it, but living with it – or not. The dissolution of the non-existent Knight proves the point, as he has nothing of his own to construct his individuality from once deprived of the orders and duty from above. Where humanity can survive is where we can live with our imperfection.

The Trilogy thus tackles head-on the void, the negative, the nothing. This could be, and has been the recipe for modernity’s great pessimistic turn, showing humanity not so much after the fall from grace, but having never had anywhere to fall from and hence no place to hope to regain. Paradise lost? No no. Paradise insanely dreamt of and now sanely acknowledged as nothing but hot air. But where Schopenhauer, Nietzsche or Sartre transform this realisation into man’s struggle with a freedom he is conditioned not to take properly advantage of, for Calvino the encounter with the void is a process of achieving weightlessness, perchance to float. Negativity means getting lighter. Negation is the opposite of heaviness. If life is worth nothing, nothing surely is worth lightness.

[1] Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, 7.53.