by Richard Farr

We called my English teacher Scab for no particular reason except that it took the edge off our terror. A big man in a double breasted jacket, he wore tinted glasses that hid his expression. His head looked as if it had been carved rather carelessly from a boiled ham. “You are not going to like me,” he said to us in our first class, when I was 13. “I am the iron fist inside this institution’s velvet glove.”

It was a front, mainly. He did not suffer fools, including his pupils and most of his colleagues, at all gladly. He probably dreamed of teaching at a university, where he could have discussed Chaucer’s prosody without first getting people to stop making farting noises.

By the time I turned 17 he had softened a little, as if he could see that some of us might one day turn into bona fide human beings. And that year the national syllabus gods gifted us what was (as I gradually came to see) an absolute corker. Among other succulent morsels there were chunks of The Canterbury Tales, all of both Othello and Lear, Gulliver’s Travels, Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings, Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party.

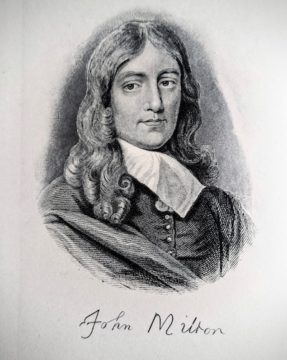

The most intimidating item by far was Paradise Lost Books IX and X — a hundred-score lines of theology that we found impenetrable, as if we were trying to hack our way back into an overgrown Eden long after its attendants’ banishment. Our feet tangled in the archaic vocabulary. Classical allusions stung our ignorant faces at every turn. (“Of Turnus for Lavinia disespous’d”? “Not sedulous to indite”? Both of these gems were on the first page of Book IX.) Scab spent a couple of weeks trying to make sense of it all for us but we were illiterate adolescents, lost and flailing inside an erudite adult’s poem. One day he sighed melodramatically and changed tactics. “I’ll read it to you,” he said. “Don’t think. Don’t even try to think. Just listen.”

The most intimidating item by far was Paradise Lost Books IX and X — a hundred-score lines of theology that we found impenetrable, as if we were trying to hack our way back into an overgrown Eden long after its attendants’ banishment. Our feet tangled in the archaic vocabulary. Classical allusions stung our ignorant faces at every turn. (“Of Turnus for Lavinia disespous’d”? “Not sedulous to indite”? Both of these gems were on the first page of Book IX.) Scab spent a couple of weeks trying to make sense of it all for us but we were illiterate adolescents, lost and flailing inside an erudite adult’s poem. One day he sighed melodramatically and changed tactics. “I’ll read it to you,” he said. “Don’t think. Don’t even try to think. Just listen.”

What happened next I can’t articulate with any clarity, except to say that the words melted onto his tongue like expensive chocolates, rendering his voice thick and smooth, and it was as if he had become Milton; it was as if I was present at the creation and was witnessing the poem erupt for the first time from the dark materials of the blind freedom-fighter’s imagination.

“Don’t think. Just listen.”

When Satan, who late fled before the threats

Of Gabriel out of Eden, now improv’d

In meditated fraud and malice, bent

On mans destruction, maugre what might hap

Of heavier on himself, fearless return’d

From compassing the Earth; cautious of day,

Since Uriel Regent of the sun, descri’d

His entrance, and forewarnd the Cherubim

That kept thir watch; thence full of anguish driv’n,

The space of seven continu’d Nights he rode

With darkness; thrice the Equinoctial Line

He circl’d; four times cross’d the Carr of Night

From Pole to Pole —

He went on for almost an entire class session, escaping from us into the poem. I don’t know what if anything the reading did for the other boys in the class. For me it was an epiphany. I dropped my head into my hands as tired students will whose eyelids have been crushed shut like grape skins by the heel of sleep. But I wasn’t tired. I’d never felt more awake in my life.

Maugre what might hap / Of heavier on himself!

Now improv’d / In meditated fraud and malice!

Regent of the sun!

Four times crossed the Carr of Night!

I didn’t have a clue what the Carr of Night was but I didn’t care — I was bewitched by the blue electric crackle the phrase made as it pinged around in my head. And oh to have the vision, the agility, the vinegary intelligence to use the verb improv’d just there! It was the first time I’d experienced that emotion all authors know, the sour-sweet cocktail of jealousy and admiration that hits your palate like poison-spiked champagne when you recognize the superior phrase, the superior talent. Oooh oooh oooooh where could I buy ink in all these pretty colors?

I didn’t have a clue what the Carr of Night was but I didn’t care — I was bewitched by the blue electric crackle the phrase made as it pinged around in my head. And oh to have the vision, the agility, the vinegary intelligence to use the verb improv’d just there! It was the first time I’d experienced that emotion all authors know, the sour-sweet cocktail of jealousy and admiration that hits your palate like poison-spiked champagne when you recognize the superior phrase, the superior talent. Oooh oooh oooooh where could I buy ink in all these pretty colors?

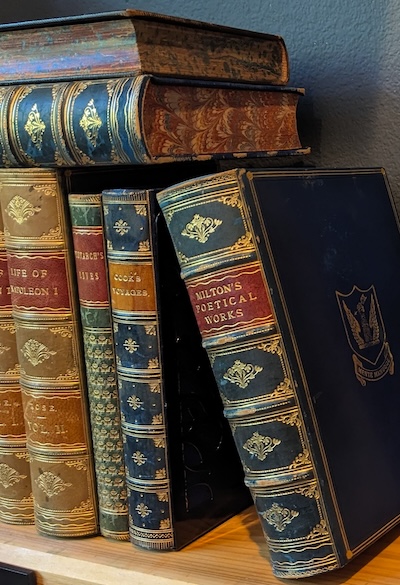

Later that year my grandfather died and my mother passed on to me a dozen of his books. Each one is jacketed in tooled leather, with the spines picked out in red and gold. Each is a different school prize that he won a few years before the trenches. Cook’s Voyages (1st Form Prize, 1904). The Works of William Shakespeare (Prize for Latin, 1904). Bacon’s Essays (Prize for Latin, 1905). Plutarch’s Lives (Prize for Choir, 1905). Carlysle’s The French Revolution (Combined Prize for Mathematics and Piano, 1907). The one I treasure most (2nd Prize for Scripture, 1907) is Milton’s Poetical Works:

— thus the Orb he roam’d

With narrow search and with inspection deep

Consider’d every Creature, which of all

Most opportune might serve his Wiles, and found

The Serpent suttlest Beast of all the Field.

That book could have become a relic in the attic. Because of Scab it sits with its companions in easy reach behind my desk, near a framed photograph of its original owner. I pick it up all the time.

*****

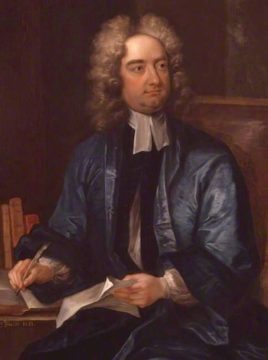

Swift was easier than Milton. After Scab had helped us decode his archaic language and assault the barricade of his antediluvian political obsessions, the reward was to discover that Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, by Lemuel Gulliver is not only violent, misanthropic, subversive, pessimistic, disturbingly angry and thrillingly obscene, but also (icing on the cake) one of the funniest books ever written. Scab lost no time in taking us to the key question: why is it funny?

“Swift’s power as a writer depends on his sense of humor,” he said. “And his humor depends on his narrator’s earnestness. Nearly all true wit has its roots in the contrast between two mutually incompatible views of the world. And what we laugh at STOP LOOKING OUT OF THE WINDOW FARR YOU IDLE BOY what we laugh at is the contrast between our own more sophisticated view of reality and the narrator’s ignorant one.”

Looking out of the window was a reasonable thing to be doing. It was spring. There was sun on the grass. And — surely one of the loveliest phenomena in all nature — the buds on the chestnut trees had begun to split open like rubbery lips and stick out their insolent lime green tongues. In any case I’d been listening closely enough to grasp what Scab was up to: he was explaining irony. (Lemuel Gulliver. Lemming. Gullible. Geddit? We hadn’t got it. He’d pointed it out.) Eironeia, he said, was literally dissembling. Except that in irony you and the victim of your dissembling share the joke, so that instead of being a form of dishonesty it is a powerful new tool of mutual understanding. Especially when the subject is the absurdity of the world.

Unsure whether we were on board, he amazed us by producing a Monty Python record. Hoots of delight filled the room. “I’m going to play something I know you’ll enjoy,” he said. “Let’s listen shall we? And then I’ll explain to you why it isn’t funny.”

I’d already heard the Lumberjack Song umpteen times. I’d also seen Michael Palin perform it on television, with Connie Booth as his “best girl by my side,” so I could picture him in his plaid shirt and padded hat, singing lustily in the forest:

I’d already heard the Lumberjack Song umpteen times. I’d also seen Michael Palin perform it on television, with Connie Booth as his “best girl by my side,” so I could picture him in his plaid shirt and padded hat, singing lustily in the forest:

I cut down trees, I eat my lunch,

I go to the lavator-eee….

On Wednesdays I go shopping,

Have buttered scones for tea.

A choir of Canadian Mounties repeats the verse in the background. But at the point where the song starts to veer dangerously off-course (I cut down trees, I skip and jump, I like to press wild flowers) Scab picked the arm up off the record. “So far so good. It’s quite funny up to here. Not very funny, but promisingly ridiculous wouldn’t you say? We’re being teased into a world we didn’t expect. Skip and jump? Press wild flowers? We’re becoming unsettled. We’re no longer sure where we are. Now listen for the mistake.”

With a pop and a squeak the needle went down again.

I cut down trees, I skip and jump,

I like to press wild flowers.

I put on women’s clothing,

and hang around in bars.

Sheer momentum takes the Mounties through the phrase “women’s clothing,” but it’s like watching Wile E. Coyote going over a cliff. There’s a couple of seconds of lag before they react: “Hang around in bars?”

The Mounties do try to regroup. They plaster their grins back in place and get through most of another verse. But the material proves too rich for them:

I cut down trees, I wear high heels

Suspendies and a braaaa,

I wish I’d been a girlie

Just like my dear Papaaaa.

How this could fail to be thought funny was inconceivable to me. The last line was pure genius of course, though what tipped me over into crying with laughter was the image in my mind of the clueless delight on Palin’s face.

Scab rubbed his hands gleefully and shocked us into full attention by smiling. “So. We are being told a joke. One version of the joke is that the forests of British Columbia are full of choruses of Mounties who sing along with cross-dressing lumberjacks. That takes an existing stereotype and turns it on its head. It presents a world in which this is unremarkable in order to ask what the world would be like if it were unremarkable. But that requires the Mounties to be plausible characters in that world — in which case they should keep on grinning and keep on singing as if nothing has happened. Why then do they seem to agree with us that there’s something wrong with what the lumberjack is singing? Why do they share our prejudices? That only makes sense if the sketch is taking place here, in this world. But in that case the sketch is nothing but the record of an encounter with one eccentric lumberjack. Don’t you see what they’ve done? They’ve fatally nudged you in the ribs. They’re afraid you won’t get the joke so they’re saying ‘Look, look, here’s the joke! Don’t miss it!’ And that destroys the joke.”

I can see him now, brandishing his copy of Gulliver above the record player, almost ranting. “Swift doesn’t make that mistake. He has more confidence in himself. Or more confidence in us. At all events he keeps a straight face about Lemuel’s naïveté to the end. That’s what makes the first three books of Gulliver such an effective comic attack on his political and social world. It’s also what makes the final book such a disturbing attack on, well, everything. Look again at those Houyhnhnms. So rational. So much better than the Yahoos. So completely lacking in all our base passions, our neediness and attachments and addictions. Lemuel falls for them abjectly. He learns to love them so much that in the process he becomes disgusted by his own species, including his own wife and children. But whose side is Swift on? He won’t tell us. And why won’t he tell us? Because he’s a great artist, which means that he hopes to help the rest of us wake up and think. Also of course for another reason. Swift is Swift. But he’s also Gulliver. Which is to say: he is a human being driven to the brink of insanity by the insoluble contradiction between reason, which makes life bearable, and passion, which makes it worth living.”

I can see him now, brandishing his copy of Gulliver above the record player, almost ranting. “Swift doesn’t make that mistake. He has more confidence in himself. Or more confidence in us. At all events he keeps a straight face about Lemuel’s naïveté to the end. That’s what makes the first three books of Gulliver such an effective comic attack on his political and social world. It’s also what makes the final book such a disturbing attack on, well, everything. Look again at those Houyhnhnms. So rational. So much better than the Yahoos. So completely lacking in all our base passions, our neediness and attachments and addictions. Lemuel falls for them abjectly. He learns to love them so much that in the process he becomes disgusted by his own species, including his own wife and children. But whose side is Swift on? He won’t tell us. And why won’t he tell us? Because he’s a great artist, which means that he hopes to help the rest of us wake up and think. Also of course for another reason. Swift is Swift. But he’s also Gulliver. Which is to say: he is a human being driven to the brink of insanity by the insoluble contradiction between reason, which makes life bearable, and passion, which makes it worth living.”

The next time I listened to the Lumberjack Song I discovered that something in me must have agreed with Scab from the start, because I had been hearing the ending incorrectly. Palin’s ‘best girl’ has spent the whole time staring up at him in adoration. On that last “Papaaaa…,” she is finally overcome with emotion and reacts with a wail of — what? I had assumed that her line was “Oh Dennis! I think you’re so… rugged!” I’d treasured this as the coup de grâce, the punchline, the most epically funny thing in the whole sketch. Imagine my disappointment then on grasping that she’s with the Mounties. She too is confused and embarrassed. What she says is only the predictable, not-funny “Oh Dennis! I thought you were so rugged.”

Though an ardent Python fan I was OK with Scab slaughtering this small and particular sacred cow — thrilled to bits in fact by the discovery that instead of just consuming something like comedy and noting in passing the degree to which you enjoyed it, you could treat it as literature and analyze what was going on. After so much useless sullen toil over French irregular verbs, annual average rainfalls, and the impenetrably complex tide-tables of the Hundred Years War — facts facts facts — it was like being handed a blade. You could cut into everything around you and examine minutely how it worked. Better yet, you could pontificate to other people about why their tastes were inferior to yours.

In the movie version of my life I go back to visit Scab in the retirement home and over cups of Earl Grey I tell him what an enormous difference he made to me. In reality I left that gesture many years too late. The best I can do now is set down the fact that — while the rest of the syllabus was pretty wonderful too — those hours on Milton and Swift were the most thrilling I ever spent in a classroom.