by Andrea Scrima

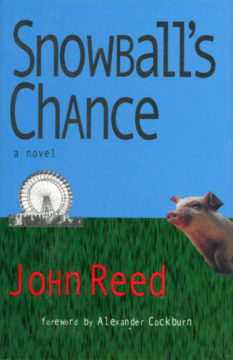

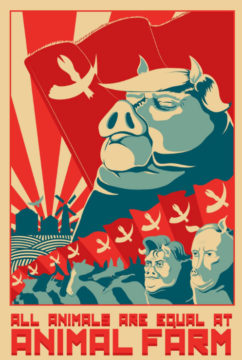

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Snowball’s Chance, it turns out, was only the beginning. The book was published the same year as Hitchens’s Why Orwell Matters, and the media frequently paired the two. In the years that followed, Reed wrote a series of essays (published in The Paris Review, Harper’s, The Believer, and other journals) analyzing the heated response to the book and everything it implied. Orwell’s writing had long been used as a propaganda tool, and evidence had emerged that his political leanings went far beyond defaming communism—but if facing this basic historical truth was so unthinkable, what was the taboo preventing us from seeing? Reed’s examination of our Orwell preoccupation sifts through the changes the West has undergone since the Cold War: its cultural crises, its military disasters, its self-deceptions and confusions, and more recently—perhaps even more troubling—its new instability of identity. The Never End brings together nine of these essays and adds an Animal Farm timeline, a footnoted version of Orwell’s proposed preface, and the Russian text Animal Farm originally drew from to more clearly assess the circumstances behind, and the conclusions to be drawn from, the book’s global importance.

Andrea Scrima: John, to start off with, I’d like to talk about this decades-long mission of yours to demystify George Orwell and shed light on his lesser-known political leanings and activities. One of the aims at the heart of this project, and your earlier book Snowball’s Chance, has been to reveal that Animal Farm does not, as has been generally claimed, describe the dangers of totalitarianism as such but rather the dangers of rebellion and revolution. In your new book The Never End, you delineate Animal Farm’s hidden agenda: to squelch any incipient rumblings of progressive reform. The message to readers on the Western front of the Cold War—and particularly schoolchildren, because Orwell’s books have been part of the standard curriculum for over seventy years—has been that revolution, even when it’s unleashed not by the rabble-rousing mob but by the educated class, and for all the right reasons—is, due to our flawed human nature, doomed to failure. Meaning: better to maintain a status quo that is admittedly less than ideal than risk chaos.

Andrea Scrima: John, to start off with, I’d like to talk about this decades-long mission of yours to demystify George Orwell and shed light on his lesser-known political leanings and activities. One of the aims at the heart of this project, and your earlier book Snowball’s Chance, has been to reveal that Animal Farm does not, as has been generally claimed, describe the dangers of totalitarianism as such but rather the dangers of rebellion and revolution. In your new book The Never End, you delineate Animal Farm’s hidden agenda: to squelch any incipient rumblings of progressive reform. The message to readers on the Western front of the Cold War—and particularly schoolchildren, because Orwell’s books have been part of the standard curriculum for over seventy years—has been that revolution, even when it’s unleashed not by the rabble-rousing mob but by the educated class, and for all the right reasons—is, due to our flawed human nature, doomed to failure. Meaning: better to maintain a status quo that is admittedly less than ideal than risk chaos.

It reminds me of that moment shortly after the pandemic hit when a mood of hope began to spread: nature had finally struck back, and humanity was recognizing the stark truth of its situation: that to survive, it would have to scale back virtually everything we associate with modern life and reduce the monster of production to a minimum. Suddenly, it was like getting a fleeting glimpse through a veil: the late-capitalist system of forever war we’re living in was created by humans and can therefore be changed by humans; it was possible to shift course, we just had to take responsibility and start. In retrospect, it’s sad to see how quickly the revolutionary power in that insight gave way to fear and resignation as we obeyed the powers that be and waited for the vaccinations that would save us—but for a moment there, our collective situation, and our collective power to change it, had become briefly, startlingly clear.

And so it seems to me that you’re looking at the great force arising out of hope—and why it’s essential for those in power to snuff it out as early as possible. What bearing does this have today?

John Reed: You speak beautifully to the core agenda of Animal Farm: learned helplessness. I wrote Snowball’s Chance on pure instinct; I was a different kind of public-school kid than Eric Blair, and read the text over and over again in the pews of my NYC classrooms. With 9/11, the message of the text was suddenly clear. Had Orwell thought he could collaborate and then shake off the monstrosity? Quite probably. But he died leaving his tainted legacy still tainted; in fact, his death only allowed that much more manipulation of the text and its presentation. When I was sucked into this discussion as a result of Snowball’s Chance, I was shocked by the cries of heresy. What I was saying, what I discussed, was merely the historical record. Twenty years later, people are willing to grant that—but only those who care to grant there even is a historical record. The anti-historical tendency of present-day media (I hesitate to call it social) isn’t too concerned with history. And, alas, I have a sense that generationally we are moving into an era where people expect everything to be broken and riddled with lies. People can’t even get angry about it. That would be just too much for our psyches to endure.

A.S.: A decade ago, you wrote an essay for Harper’s about the little-known fact that “Animal Riot” by Nikolai Kostomarov formed the departure point for Animal Farm. Interestingly, Kostomarov’s animals succeed in throwing off the yoke of oppression: this is one main difference to Orwell’s view of uprising and revolt, but in what other ways did Orwell’s message differ?

J.R.: Well, Orwell’s little squib is a much-improved bit of writing—better characterizations, more pathos, deeper analogs. The complexity of a revolution, failures and all, of course makes Animal Farm a much more interesting narrative. Did the farm animals have to be, by nature, dumber than the pigs? In its inception, Animal Farm is a concession of classist values.

A.S.: And it suggests that certain species—the pigs—have the birthright to rule.

Photo: David Shankbone

J.R.: Yes. That’s the terrible revelation of Animal Farm, and why it was such an effective act of propaganda. Orwell was so dimly aware of his own classicism that he couldn’t even see it; when the message of the farm was taken to be anti-revolutionary, he thought it was a misinterpretation. But it was the single, inevitable conclusion, and the reason that Animal Farm as a text is ultimately unredeemable.

A.S.: Did Orwell’s dystopian vision plant the seeds of Western paranoia?

J.R.: Oh, I think these visions and fears were in place well before Orwell. Fears of the working class date back to the early nineteenth century, at least in an industrial sense. Re: Dickens and his American Notes. The labor unrest of the later part of the nineteenth century was particularly disturbing to moneyed elites. The dystopian vision, as well, dates back to the nineteenth century with H.G. Wells, etc. I suppose the Russian Revolution gave us a more modern incarnation: Mayakovsky and others. In investigating the sources of Animal Farm, I pretty well lay out Orwell’s pattern of influences.

A.S.: Another major flaw in Orwell’s portrayal of the class struggle is the absence of an intellectual class or intelligentsia—Orwell’s own class—which, of course, provides power with its arguments and justifications. Apart from the pigs, he made the animals a little too stupid.

J.R.: Yes, that’s exactly the problem. Class=species. The equation presumes the classes with a justification of economic Darwinism, or even eugenics.

A.S.: In 1948, the British Foreign Office formed the Information Research Department, a clandestine government organization dedicated to anti-communist propaganda. One of its tools was to spread its agenda through literature; among the authors the IRD championed were Bertrand Russell, Arthur Koestler, and of course Orwell himself, whose Animal Farm it published and relentlessly republished, promoted, and translated over the years. Orwell reciprocated by supplying the IRD with lists of communist sympathizers—chiefly artists, writers, and intellectuals—and anyone else deemed to be an enemy. When did this first become known?

J.R.: The documents were declassified in a slow, decentralized process—rumors mixed with facts, and outdated estimations were mingled with more recent appraisals. At this point, using Google and online sleuthing skills, it’s just about impossible to come up with a clear picture of who he turned over. There were at least two major “lists,” one in the neighborhood of 130 entries and a winnowed-down one in the neighborhood of thirty. It’s quite possible that there was a final, shorter list of the highest-priority people—maybe a list of seven or so—that resulted in real consequences that could be measured. It’s extremely unlikely that the materials we have constitute a complete picture. I discuss some of the theories I’ve come up with in the course of The Never End; I had thought to write an essay that sorted it all out once and for all, but I realized I just didn’t have enough information. I lacked the primary sources, and tbh I doubt they’re out there.

A.S.: In the year 1984—a disturbing date for anyone who’d read Orwell’s book growing up (which is to say everyone over the age of thirteen or fourteen) and was anxious about the dystopian future it prognosticated—Salman Rushdie wrote an essay accusing Orwell of “advocating ideas that can only be in the service of our masters.” Did Rushdie’s criticism resonate at the time, or was the Orwell name and myth already too powerful?

J.R.: Oh, these criticisms of Orwell’s texts, specifically Animal Farm and 1984, have been an undercurrent since their publication. Anthony Burgess published a book in the late ’70s, a series of essays and a novella, 1985, that was scathingly critical of Orwell. So much so that the anger makes the prose kind of confusing.

A.S.: In 1950, the CIA created the Congress for Cultural Freedom with similar aims to those of the IRD, and it invested heavily in writers and artists who served as a cultural counterweight to the Soviet system. In Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, Frances Stonor Saunders revealed, among other things, the degree to which the American Abstract Expressionists were promoted as a paragon of Western freedom in stark contrast to the small, cramped canvases of Socialist Realism. The ideological appropriation of art isn’t new, but the swashbuckling persona of Western democracy became a cultural trope designed to lure Western Europe away from, as Stonor Saunders puts it, “its lingering fascination with Marxism and Communism towards a view more accommodating of ‘the American Way.’” When did the CIA first realize that Orwell could become an ideological figurehead?

J.R.: A little speculative, but I think the inspiration to deploy Animal Farm came directly from the British Foreign Office and the early days of the Information Research Department, specifically from Arthur Koestler, or Celia Kirwin, who also worked with the IRD and was the twin sister of Koestler’s wife-to-be. Then came Animal Farm’s inclusion in general Congress for Cultural Freedom operations, and then, after Orwell’s death, the CIA entered properly with the film version. I worked on a timeline for the Paris Review, which was incidentally a beneficiary of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, that maps this out. In The Never End, I fill out the timeline a bit more.

A.S.: You also discuss the protection of parody—the change in copyright law and practice in Britain and US from the beginning of the millennium, when Snowball’s Chance was first published, to the present time. How potent a form is parody today?

A.S.: You also discuss the protection of parody—the change in copyright law and practice in Britain and US from the beginning of the millennium, when Snowball’s Chance was first published, to the present time. How potent a form is parody today?

J.R.: Hmm, well, it’s still protected in the United States; in fact, the protections that look like they’d be diminished have been upheld by a conservative Supreme Court. A tradition of parody and satire is very much in the bones of conservatives, it turns out. Is it less effective today? I have been thinking about this lately. I’m categorized as a Gen Xer, but I was on the tail end of that. In the ’90s, the fashion was different, as was the attitude—that sincere but self-destructive bit was pretty much passé, and we were shining with our insincerity. In fact, the Gen Xers quite hated us for it. The response was something that would gradually coagulate into this shapeless blob of literary movement, New Sincerity, which is as entitled as it is putrescent. We were right, through the ’90s, our terrible revelation of shining insincerity was the greatest weapon we had in our attack on normative culture. Successful. Yes, to some degree. But were they right as well? Did we spoil the joke? Did our snarky ’tude contaminate all criticism, and make any kind of constructive discussion impossible? Prolly.

A.S.: In your essay “The Politics of Narrative,” reprinted in The Never End, you examine the similarities between censorship imposed from above and the inescapability of the conformist narrative, our own form of self-imposed censorship:

In writing, in publishing, the questions translate: do I “sell out,” do I change the system, or do I take refuge in “alternative” publishing? [. . .] In America, the fantasy of professional creativity is freedom. The US reality of professional creativity is one of subservience and unrelenting regulation. [. . .] For those who do achieve some level of autonomy, the cost is total compromise; in their work, they are to promote assimilation, social passivity, and/or the inane reductivisms of social media.

J.R.: Sadly, social media has only exacerbated the circumstance. People think there’s a choice. I hear it all the time: young writers and artists saying they’re willing/ready/planning to sell out. They think that means they’ll cash in. Probably not. What it does mean: they’ve allowed themselves, and their own work in their own estimation, to be devalued.

A.S.: Generally, when people think of Orwell, it’s the totalitarian state and its sinister methods of mind control that come to mind. We rarely apply these ideas of indoctrination to ourselves. How Orwellian is Orwell’s influence on the West?

J.R.: Orwell thought he could sort it out in the end, I think. But I don’t suppose there’s very much left of him now. People will often tell me that the War Commentaries are what’s really important, for example, but they’re not. Orwell’s journalism is so mired down in day-to-day squabbles that it’s nonsense in 2023. What’s left of Orwell is a legacy of collaboration. And if it weren’t for his collaborations with Soft War directives, we wouldn’t remember him at all.

J.R.: Orwell thought he could sort it out in the end, I think. But I don’t suppose there’s very much left of him now. People will often tell me that the War Commentaries are what’s really important, for example, but they’re not. Orwell’s journalism is so mired down in day-to-day squabbles that it’s nonsense in 2023. What’s left of Orwell is a legacy of collaboration. And if it weren’t for his collaborations with Soft War directives, we wouldn’t remember him at all.

A.S.: Does a book like The Never End have legs, since it so effectively goes after the icon of liberal aristocracy, or do academics effectively bury it? I guess it’s up to the classrooms of the English-speaking world to keep this history alive.

J.R.: It’s a bit of a victory lap regardless? The origin of Animal Farm is now in the record books, as is the propagandistic nature of Animal Farm. I do think you’re right, though, that it’s a long, toilsome march ahead (The Never End). Still, we will get to see the conversation around Orwell totally turn the way we saw back in 2001. It’s already happened; we’re just watching the provinces realize it. The more grandiose question is whether the edifice of post-World War II propaganda will crumble. Has that narrative finally spoiled? I expect it has, but that, like Orwell, the influence, the hegemonic influence, will suspire unspectacularly over the course of decades. And yes, it would be nice if someone gave me the bottle of Ardbeg Hitchens reneged on.

A.S.: It’s interesting that the immediate danger of the WWII era, Hitler, is altogether absent from Animal Farm. Instead of fascism, which the American right continues to flirt with to this day, it’s the fear of communist revolt that planted dread in the hearts of schoolchildren. Realistically speaking, the prospect of a totalitarian takeover was pretty far-fetched; the real danger seems to have been allowing young people to develop their critical faculties and historical understanding far enough to seriously question the status quo and consider what a truly equitable society might look like. Because the fear of a totalitarian communist dictatorship taking over was largely a cover for the fear of a well-organized uprising of the working class aimed at wealth redistribution and unseating the privileged elite. Do we have Orwell to thank, in part at least, for our psychic need to think in polarities?

J.R.: We don’t have Orwell to thank for it, but he understood it. That kind of bombast, again, is distinctly nineteenth century, but Orwell’s brand of self-righteousness, his lone-man, contrarian with the truth, was shaped by media, radio in particular, into a form that remains dominant to this day. Rush Limbaugh, Tucker Carlson, whoever. Orwell, much like the power pundits of our moment, despite his espousals, was never much of a contrarian; he mostly asserted partisan positions. The other irony is that truth and partisan truth have grown so far apart as to be completely disparate; the lone voice of truth now presumes, insists upon, lies to itself and everyone else. I don’t expect that final step is one Orwell would have taken.

J.R.: We don’t have Orwell to thank for it, but he understood it. That kind of bombast, again, is distinctly nineteenth century, but Orwell’s brand of self-righteousness, his lone-man, contrarian with the truth, was shaped by media, radio in particular, into a form that remains dominant to this day. Rush Limbaugh, Tucker Carlson, whoever. Orwell, much like the power pundits of our moment, despite his espousals, was never much of a contrarian; he mostly asserted partisan positions. The other irony is that truth and partisan truth have grown so far apart as to be completely disparate; the lone voice of truth now presumes, insists upon, lies to itself and everyone else. I don’t expect that final step is one Orwell would have taken.

A.S.: In Animal Farm, the mindless bleating of the sheep at the slightest hint of dissent—“Four legs good, two legs bad”—and later “Four legs good, two legs better”—immediately brings to mind “Lock her up” and other Trump rally slogans. The falsification of the animals’ history to the point that they doubt their own memory—one of the ABCs of propaganda—calls to mind the “fake news” strategy of manipulating objective fact long enough until everyone believes the lie. Looking at the political landscape in America, it’s hard not to think that we really are as stupid as the animals on Orwell’s farm. But in your retelling of the story, Snowball finally has his chance: he returns from exile and introduces neoliberal economics, corporatism, and a parochial, mindlessly optimistic cultural dictate that echoes the pre-9/11 era. The “terrorist” attacks on the Twin Mills offer the powers that be—the pigs—the perfect pretext to channel a growing wave of repressed rage over capitalism’s injustices into a collective frenzy of xenophobic hatred and bloodlust.

J.R.: Let’s not say that the animals are as smart as the pigs; let’s say that the pigs are as stupid as the animals.

John Reed is the author of A Still Small Voice (Delacorte), The Whole (Simon & Schuster/MTV Books), the SPD bestseller, Snowball’s Chance (Roof/Melville House), All the World’s a Grave: A New Play by William Shakespeare (Penguin/Plume), Tales of Woe (MTV Press), Free Boat: Collected Lies and Love Poems (C&R Press), A Drama in Time: The New School Century (Profile), The Family Dolls: A Manson Paper + Play Book (Outpost19), and The Never End: The Other Orwell, the Cold War, the CIA, and the Origin of Animal Farm (forthcoming, Palgrave Macmillan). MFA in Creative Writing, Columbia University (fellowship); published in (selected) ElectricLit, The Brooklyn Rail, Tin House, Paper Magazine, Artforum, Hyperallergic, Bomb Magazine, Art in America, The Los Angeles Times, The Believer, Rumpus, Observer, the PEN Poetry Series, Daily Beast, Gawker, Slate, Paris Review, Times Literary Supplement, Wall Street Journal, Vice, The New York Times, Harpers, Rolling Stone; anthologized in (selected) Best American Essays (Houghton Mifflin); works translated and performed worldwide; films distinguished at festivals internationally; two-term board member of the National Book Critics Circle; Associate Professor and Director of the MFA in Creative Writing at The New School.

Andrea Scrima has been living as an author and visual artist in Berlin since 1984. Her first book, A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil), appeared in 2010, a second edition in 2018; the German translation was published by Literaturverlag Droschl (Wie viele Tage) in 2018. The novel Kreisläufe (Like Lips, Like Skins), excerpts of which have appeared in Zyzzyva, manuskripte, and Trafika Europe, followed in 2021. Scrima writes essays for the Times Literary Supplement, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Schreibheft, Music & Literature, The American Scholar, LitHub, The Millions, manuskripte, and The Brooklyn Rail, among others; is editor-in-chief of the literary journal StatORec; and publishes a regular column at Three Quarks Daily. In 2020, she co-edited the anthology Writing the Virus, a New York Times Sunday Book Review “New & Noteworthy” title of 2021. Scrima won a National Hackney Literary Award in 2007 and the Glimmer Train Fiction Open in 2010. Writing fellowship and several research grants from the Berlin Senate; fellowship from the Deutscher Übersetzerfonds (German Translator Fund). Residencies at Schloss Salem (Überlingen), Ledig House / Art Omi (New York), the Villa Romana (Florence); and the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation (Taos, NM). Currently on a one-year fellowship as writer-in-residence (Stadtschreiberin) of the city of Graz, Austria.

![]()