By Tolu Ogunlesi

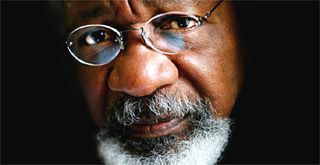

Lamenting the presence of Nigeria on the US government’s list of “countries of interest” (in the war on terror), Nigerian writer and first African Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka told British journalist Tunku Varadarajan, at the Jaipur Literary Festival in January: “[Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab] did not get radicalized in Nigeria. It happened in England, where he went to university.”

Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab is the 23 year old Nigerian man whose arrest on Christmas Day 2009 while attempting to detonate a bomb aboard a Detroit-bound plane caused the country's blacklisting.

In 2005, at the age of 19, Umar Farouk enrolled in the University College London (UCL), for a degree in ‘Engineering with Business Finance’, after high school at a British-curriculum school in Togo. From all indications UCL kept the young man busy. In his second year he was elected President of the Student Union’s Islamic Society, organizing a “War on Terror Week” during his tenure.

Soyinka’s England

Five decades before Umar Farouk became a student in England, Wole Soyinka was admitted to the University of Leeds. In October 1954 the future Nobel Laureate left the sleepy city of Ibadan, Western Nigeria (where he was studying at the University College), for England. He was 20. Soyinka would spend the next six years in England, returning to Nigeria on the eve of the country’s independence from Britain.

It can be argued that England was the breeding ground for Mr. Soyinka’s genius; the playwright was, in a sense, forged between the stiff upper lips of Poundland. It wasn’t only Soyinka the playwright that was made in England. Soyinka the father was too. He would during his time in that country fall in love with an English woman, who in 1957 bore him a son, his first.

It can be argued that England was the breeding ground for Mr. Soyinka’s genius; the playwright was, in a sense, forged between the stiff upper lips of Poundland. It wasn’t only Soyinka the playwright that was made in England. Soyinka the father was too. He would during his time in that country fall in love with an English woman, who in 1957 bore him a son, his first.

When Mr. Soyinka left for England, the Nigeria he was leaving behind was merely one colony in an Empire that stretched across the world, and Mr. Soyinka was a subject of the Queen of England. The England he was leaving for was not the one in which multiracialism had become the politically correct thing; this was still an England that wore its racism rather comfortably on its sleeves. One of Mr. Soyinka’s most anthologized poems dates back to that time, a cheeky send-up of racism, which to all intents may have been autobiographical:

It features a young black man in England, speaking on the phone with a potential landlady. The phone conversation is a prelude to a face-to-face meeting. But he feels the need to make a “self-confession”:

“Madam,” I warned, / “I hate a wasted journey—I am African.” / Silence.

The landlady’s interest is piqued.

“HOW DARK?”. . . “ARE YOU LIGHT / OR VERY DARK?” she wants to know. She repeats herself, for emphasis.

“You mean – like plain or milk chocolate?” the narrator suggests. Then he has a color-coded brainwave. “West African sepia,” he concludes.

Read more »

I once wrote a political column for Fox News. My point of view was liberal and at times decidedly leftist.

I once wrote a political column for Fox News. My point of view was liberal and at times decidedly leftist.