by Rafaël Newman

As forced migration in the wake of war and climate change continues, and various administrations attempt to additionally restrict the movement of people while further “freeing” the flow of capital, national borders, nativism, and a sense of cultural rootedness have re-emerged as acceptable topics in a globalized order that had until recently believed itself post-national. In the German-speaking world, where refugees have been met with varying degrees of enthusiasm depending on their provenance, national pride, long taboo following the Second World War, at least in Germany, is enjoying a comeback. As the last generation of perpetrators and victims dies and a newly self-confident, unproblematically nationalist generation comes to consciousness, it is again becoming possible to use a romantic, symbolically charged term like Heimat.

As forced migration in the wake of war and climate change continues, and various administrations attempt to additionally restrict the movement of people while further “freeing” the flow of capital, national borders, nativism, and a sense of cultural rootedness have re-emerged as acceptable topics in a globalized order that had until recently believed itself post-national. In the German-speaking world, where refugees have been met with varying degrees of enthusiasm depending on their provenance, national pride, long taboo following the Second World War, at least in Germany, is enjoying a comeback. As the last generation of perpetrators and victims dies and a newly self-confident, unproblematically nationalist generation comes to consciousness, it is again becoming possible to use a romantic, symbolically charged term like Heimat.

The nuances of the word Heimat are difficult to capture economically in English: it suggests origin, community, group identity, and comforting familiarity, and is only narrowly conveyed by either the simple cognate “home”—which is somehow too particularly British, too private and individual—or by the compound “homeland,” with its unpleasant resonances of the cynical Apartheid-era term for what amounted to enforced reservations for black South Africans. Heimat connotes both birth family and wider ethnic belonging; it is both a distinct physical place and a sentimental, even ideological abstract; it conjures up both history and destiny.

October 14 this year will see the 150th birth anniversary of a German-Jewish philosopher in whose thought and life Heimat played a central role. Margarete Susman was born in 1872 in Germany and died in 1966 in Switzerland; a commemorative conference this month in both countries will mark the occasion of her sesquicentennial, and celebrate her multifaceted work, not yet as widely known as that of some of her illustrious contemporaries and colleagues, who included Georg Simmel, Martin Heidegger, Ernst Bloch, and Martin Buber. The conference is being held in two legs at consecutive locations: in Munich, where Susman studied and published, and in Zurich, where she spent her early years and much of her adult life, in exile from Nazi Germany, and where she is buried.

Willi Goetschel, a leading Susman scholar and one of the organizers of the conference, has recently published a chapter on her work and significance in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, where he summarizes Susman’s thinking on Heimat and its implications in the interwar period thus:

For Susman, homelessness, alienation, exile, hope, and redemption are more than terms that help us articulate the loss, failures, and the aspirations that inform the modern experience. They also demonstrate that we can only grasp the predicament of modern existence if we are willing to scrutinize it by sourcing the critical potential that the biblical tradition offers. Like Hermann Cohen, Buber, and Rosenzweig, who likewise have recourse to the “sources of Judaism” (Cohen 1919) in order to examine the predicament of modern existence, Susman finds in the Jewish tradition a vital resource.

The primordial condition in which humans find themselves is characterized by homelessness and suffering. Facing the infinitude of the world as the finite beings that we are, we experience the world as over against us and strange. The certainty of our future death reminds us that we are something other than the world.

Following the defeat of the Third Reich and the revelations of the full extent of the Holocaust, Susman, for whom “Human life is per se existence in an alien world and as such suffering,” was to use the Jewish experience of loss of home, homeland, and finally life on earth, and of the radical certainty of death, yet more intensively to lend further practical significance to this philosophical idea. (She had been born into an assimilated Jewish family but was to return to Judaism later in life, even as she maintained productive intellectual contact with Protestant theology.) And she would continue to consider her own religious experience, as she had been doing since her earliest years as a thinker, not only in the form of philosophical works, on such topics as love, Spinoza’s metaphysics, and the emancipation of women, and not merely in the consolations of an intellectual engagement with questions of Jewish and Protestant thought, but in a considerable parallel corpus of lyrical poetry as well.

In Das Wesen der modernen deutschen Lyrik (The character of modern Germany poetry), a treatise published in 1910 when she was 38, Susman identifies her age as one bereft of central, master narratives such as those provided by religion, but notes the concomitant rise of poetry as the heir to some of religion’s myth-making power. Indeed, she notes that poetry is linked to both religion and philosophy by way of the trio’s primordial shared relation to myth, but adds that poetry, “of all the arts, has most solicited religion and lived by its token; in its significance for lived existence in the modern era, it is only from this standpoint that poetry can be conceived of.” Furthermore, while the rise of the individual characteristic of the modern age threatens religion, which depends on a collective consciousness, poetry is in fact strengthened by the potential of this new individualism, whose rise it has itself occasioned (with the emergence of the solo voice from the chorus), and whose performance is intrinsic to its very form. The risk to that newly emerged, lyrical individual consciousness, of course, is that it no longer feels at home.

In Das Wesen der modernen deutschen Lyrik (The character of modern Germany poetry), a treatise published in 1910 when she was 38, Susman identifies her age as one bereft of central, master narratives such as those provided by religion, but notes the concomitant rise of poetry as the heir to some of religion’s myth-making power. Indeed, she notes that poetry is linked to both religion and philosophy by way of the trio’s primordial shared relation to myth, but adds that poetry, “of all the arts, has most solicited religion and lived by its token; in its significance for lived existence in the modern era, it is only from this standpoint that poetry can be conceived of.” Furthermore, while the rise of the individual characteristic of the modern age threatens religion, which depends on a collective consciousness, poetry is in fact strengthened by the potential of this new individualism, whose rise it has itself occasioned (with the emergence of the solo voice from the chorus), and whose performance is intrinsic to its very form. The risk to that newly emerged, lyrical individual consciousness, of course, is that it no longer feels at home.

Susman’s early poetics examines such luminaries as Goethe and Rilke in their relation to the para-religious process of creating individual lived experience; but she herself had also long since joined their ranks. In a poem entitled “Kämpfe” (Struggles), included in a collection published in 1892 when she was just twenty years old, Susman confronts in lyrical form the very dissolution of religious belief she would thematize in her later literary-critical work, as well as the mounting sense of homelessness in the world that was to become an academic philosophical concern. The opening stanza is a lament:

A chaos, dark as on the first of days—

As faith in fear bent low its countenance,

Nor any voice divine was heard to say

“Let there be light!” and sweetly loose our bonds.

This nightmarish conjuring of a world grown strange ends with an apocalyptic vision of a crucifix adorned with flowers—this as imperial aggression and mounting antisemitism at the end of the 19th century are shaking the civil underpinnings of the German Belle Epoque, and Susman presumably has begun to sense the fragility of her own assimilation.

Susman would return to this urgent fiat lux theme half a century later, as the Second World War, which she was to survive in Switzerland, consumed the surrounding continent and the brutal treatment reserved for Jews and other “undesirables” had become impossible to ignore, or deny. Using similar imagery and some of the same rhymes as the poem of her youth, in “Nacht” (Night), published in 1943 in Neue Wege, a journal of religion and socialism to which she contributed regularly over decades, Susman evokes a world bereft of the creator’s presence, turned away from the face of the Lord; she beseeches God to make the world anew:

Lord, give again your order,

A new Let there be light!

Remove from where it blinds us

This ancient planet’s night!

The night engulfing Europe, and indeed much of the world, was no doubt literally palpable at the time; and yet Susman’s cry here is as much for a metaphysical as for a political remaking.

Susman was to evoke the dangers of apostasy more vividly, if in the oblique and mythical form she believed proper to lyric, in a vision of Moses’ anger at the spectacle of the Golden Calf published in her 1953 collection Aus sich wandelnder Zeit (In a time of change). “Der Knecht des Volkes” (The servant of the people) stages an allegorical depiction of the world of the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, as both superpowers seem intent on circumventing international law in pursuit of their ideological aims:

His hair and beard were both still wringing wet

When he emerged from out the heavy vapor,

The champion of his folk, in wrestling labor—

Wrestled so long, his folk forgot its debt.Strode into light: and music met his ear,

A lightly coiling, brightly festive medley;

And smiling now he broke his silence deadly,

So sweet that choir’s acclaim and welcome here!He saw: he saw the glowing work erect,

In naked desert sun the calf all golden

Ringed round by his own folk, in bliss emboldened,

He saw his folk: this folk—he, God’s subject.Broke up the tablets, struck—till he was raw

And turned away from that accursèd brood—

And groveled so that God his worship saw,

And in his folk’s place offered up his blood.

This is a Moses reminiscent of Michelangelo’s in Freud’s reading of the statue, engorged with rage at his people’s renewed homelessness in a God-forsaken world (or rather, in a world that has forsaken God) and ready to spring into violent action. It is also a highly personalized narrative of alienation and disappointment, in which the lyrical self, although presented here in the third person, is shown experiencing its own forced emergence from the chorus—now, however, not so much as a solo singer, but rather as a sacrificial lamb. Strong stuff, in the aftermath of the Shoah. (For further consideration of this poem, and of Susman’s life and work in sociopolitical context, see my Contemporary Jewish Writing in Switzerland.)

Finally, in a prophetically ominous, hesitantly conciliatory poem written towards the end of her long life, Susman once again invokes a world of apostasy, alienation, and renunciation of religious values in which she yet glimpses the faint possibility of redemption. The poet here renounces her former youthful attachment to rhyme and meter, despite her epigraph’s invocation of the most dithyrambic of German philosophers, to create a text that is part treatise and part sermon. “Heimatlosigkeit” was published in 1957, also in Neue Wege. The title, which is typically rendered “homelessness,” despite the existence of another German term (Obdachlosigkeit) to describe the situation of what is now, in the Anglo-American world, circumspectly known as being “unhoused,” might more pointedly be translated as “homelandlessness” to suggest the complex of emotions it conjures up.

How fortunate is he, who has a homeland still!

Slowly, dreadfully the day is dawning, when the

Entirety of the Earth will need administration.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Who has a homeland still? Has any mortal ever had one?

Those were but likenesses of home, as the Sabbath

Is but an image of the Kingdom we were promised.And yet in our day we have seen those likenesses destroyed as well.

Perhaps an image may be still intact somewhere—

Dream of an entirety:

Of a friendship, of love, marriage,

Unexploded being.

Perhaps, every now and then, two people,

Gazing silently into one another’s eyes,

Believing they understand each other,

And perhaps, perhaps they do, in a rare moment,

In which one becomes the other’s homeland.And there are those who seek refuge in pretty carpeted chambers,

In cushy armchairs,

Where they find the illusion of a homeland,

But these are only a flight from death,

And from the terror of life as well.

It is but a sanctuary from the final fear:

That life and death go on outside.

And if they listened, they would hear, nearby,

Quite near at hand, a muffled roar—

Footsteps of those driven out, the lost, who hasten in the darkness

Over our impoverished earth in terror,

In hordes unthinkable in size.

Not simply impoverished either—but impoverished by us.

We are all straying over hollow ground,

Cracked clods.For how, how have we administered the world,

The gorgeous star that we were given,

After we were expelled from our first homeland.

The first deed was fratricide

And fratricide has remained our deed.

It is the mark that looms above all other marks,

And we have not followed

Any angel’s voice that ever sang of peace.

If only the tiny spark of hope this night

Is not extinguished,If only faith is able still to strike a light

In wounded hearts,

And the greatest of them all, love, may yet live,

And mercy,

Its younger sister!

The note of hope struck in the poem’s final lines may perhaps be attributed to Susman’s long years residing in Switzerland, a country that had at least nominally renounced the fratricidal course of its neighbors and had allowed Jewish and other refugees from Nazi Germany, following an initial period of xenophobic resistance, to live unmolested and to continue speaking and writing in their native language; a country where the word Heimat undergoes a further inflection as Heimatort, meaning a relatively unromanticized, often quite arbitrary administrative center; a country whose multilingual, multi-confessional modern emergence as a “Willensnation” renders it at least theoretically immune to the seductions of ethnic nationalism. Having spent a formative part of her childhood in Zurich, Susman had returned there from Germany upon Hitler’s rise to power and would remain there for over three decades, until her death in 1966. She is buried in the Israelitischer Friedhof Oberer Friesenberg, on the slopes of the Üetliberg, with an idyllic view of the city in which she had, finally, found her eternal home.

The note of hope struck in the poem’s final lines may perhaps be attributed to Susman’s long years residing in Switzerland, a country that had at least nominally renounced the fratricidal course of its neighbors and had allowed Jewish and other refugees from Nazi Germany, following an initial period of xenophobic resistance, to live unmolested and to continue speaking and writing in their native language; a country where the word Heimat undergoes a further inflection as Heimatort, meaning a relatively unromanticized, often quite arbitrary administrative center; a country whose multilingual, multi-confessional modern emergence as a “Willensnation” renders it at least theoretically immune to the seductions of ethnic nationalism. Having spent a formative part of her childhood in Zurich, Susman had returned there from Germany upon Hitler’s rise to power and would remain there for over three decades, until her death in 1966. She is buried in the Israelitischer Friedhof Oberer Friesenberg, on the slopes of the Üetliberg, with an idyllic view of the city in which she had, finally, found her eternal home.

*

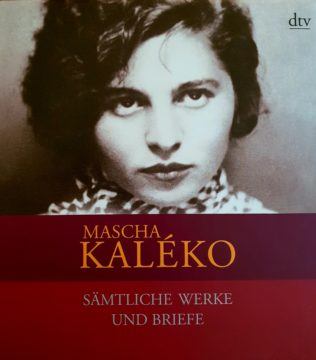

Not far from Susman’s grave, in an adjacent section of the same Jewish cemetery in Zurich, lies a younger contemporary of hers, whose background and experience echo Susman’s, but who was, for various reasons, ultimately unable to resolve her own, similarly occasioned “homelandlessness”. Mascha Kaléko, born Golda Malka Aufen in 1907 in Chrzanów, in what was then still the Austro-Hungarian Empire, lived and worked, initially in office jobs and then as a published poet, in Berlin, New York, Los Angeles, and Jerusalem. She succumbed to stomach cancer in 1975 during a brief visit to Zurich, where her burial site attracts mourning admirers to this day (as evidenced by the pebbles piled on her gravestone). Her pithy, elegant poems are typically ascribed, alongside those of Kurt Tucholsky and Erich Kästner, to the Neue Sachlichkeit or “New Objectivity” movement; she is also less formally said to be a proponent of Groβstadtlyrik, or “metropolitan poetry,” a naturalist genre first identified at the turn of the twentieth century, with the rise of the great European urban centers: see for instance her dryly anti-romantic “Grossstadtliebe” (“Love in the Big City”), in which an urban love story is limned in brief, ironic brushstrokes. But loss of Heimat, homelessness and homesickness are also recurring motifs in Kaléko’s corpus, which mingles alienation and regret with a wistfully conciliatory mood: “I have elected as my homeland love” runs one of the most celebrated lines by this eminently quotable, elegantly epigrammatic poet, who suffered enforced migration, a turbulent emotional life, difficult financial straits, and the loss of her son and beloved husband, as well as the failure ever to feel at home in exile from the Germany—the Berlin—that she had made her cultural and affective home.

Not far from Susman’s grave, in an adjacent section of the same Jewish cemetery in Zurich, lies a younger contemporary of hers, whose background and experience echo Susman’s, but who was, for various reasons, ultimately unable to resolve her own, similarly occasioned “homelandlessness”. Mascha Kaléko, born Golda Malka Aufen in 1907 in Chrzanów, in what was then still the Austro-Hungarian Empire, lived and worked, initially in office jobs and then as a published poet, in Berlin, New York, Los Angeles, and Jerusalem. She succumbed to stomach cancer in 1975 during a brief visit to Zurich, where her burial site attracts mourning admirers to this day (as evidenced by the pebbles piled on her gravestone). Her pithy, elegant poems are typically ascribed, alongside those of Kurt Tucholsky and Erich Kästner, to the Neue Sachlichkeit or “New Objectivity” movement; she is also less formally said to be a proponent of Groβstadtlyrik, or “metropolitan poetry,” a naturalist genre first identified at the turn of the twentieth century, with the rise of the great European urban centers: see for instance her dryly anti-romantic “Grossstadtliebe” (“Love in the Big City”), in which an urban love story is limned in brief, ironic brushstrokes. But loss of Heimat, homelessness and homesickness are also recurring motifs in Kaléko’s corpus, which mingles alienation and regret with a wistfully conciliatory mood: “I have elected as my homeland love” runs one of the most celebrated lines by this eminently quotable, elegantly epigrammatic poet, who suffered enforced migration, a turbulent emotional life, difficult financial straits, and the loss of her son and beloved husband, as well as the failure ever to feel at home in exile from the Germany—the Berlin—that she had made her cultural and affective home.

In “Heimweh, wonach?” (“Homesick, for what?”), a poem published posthumously in Mein Lied geht weiter (2007) on the centennial of her birth and ascribed, tellingly, to the period either of her unlucky residence in New York or of her unhappy life in Jerusalem, Kaléko invokes in her characteristically telegraphic style the topos of nostalgia, only to assign it, succinctly and definitively, to the realm of fantasy.

I mean I’m homesick, but it’s dreams I say:

The place we’re from is barely there today.

I say I’m homesick, and I mean so much:

What kept us, exiled, in its patient clutch.

We’re strangers in our homeland nowadays.

Only the sick remains.

The home’s away.

Kaléko, child of a Russian and an Austrian, had once been at home in Germany, where she enjoyed a brief popularity as a poet during the Weimar Republic, before the Nazis’ rise to power and the “discovery” that she was Jewish. She returned there, or rather to the Federal Republic, from New York after the war, in a bid to restart her career in German letters, but was unable to make a proper go of it, particularly if it meant being separated from her beloved family. And thus she remains, in death, in exile. Her grave is to be found not in Chrzanów, the city of her birth, nor in Berlin, the site of her artistic flowering, nor in New York or Jerusalem, the illustrious and fateful destinations of so many of her fellow émigrés, but in an aleatory location determined solely by religious exigency—for observant Jews must be buried as quickly as possible following their demise. A place chosen for her by chance, by arbitrary ethnic assignment, by misfortune; a home chosen by sickness. And, of course, by death. In this sense, in the Israelitischer Friedhof Oberer Friesenberg, on the slopes of the Üetliberg in Zurich, Kaléko is no less at home than Susman. And no more.

Kaléko, child of a Russian and an Austrian, had once been at home in Germany, where she enjoyed a brief popularity as a poet during the Weimar Republic, before the Nazis’ rise to power and the “discovery” that she was Jewish. She returned there, or rather to the Federal Republic, from New York after the war, in a bid to restart her career in German letters, but was unable to make a proper go of it, particularly if it meant being separated from her beloved family. And thus she remains, in death, in exile. Her grave is to be found not in Chrzanów, the city of her birth, nor in Berlin, the site of her artistic flowering, nor in New York or Jerusalem, the illustrious and fateful destinations of so many of her fellow émigrés, but in an aleatory location determined solely by religious exigency—for observant Jews must be buried as quickly as possible following their demise. A place chosen for her by chance, by arbitrary ethnic assignment, by misfortune; a home chosen by sickness. And, of course, by death. In this sense, in the Israelitischer Friedhof Oberer Friesenberg, on the slopes of the Üetliberg in Zurich, Kaléko is no less at home than Susman. And no more.