by Mark R. DeLong

We humans grasp and use things. We dwell among things. We devise new things. As a result of being so pervasive and common in experience, things qua things are practically invisible to us. For the most part, we tend to see them as things outside of us, not as something “inside” of us or capable of manipulating us even as we manipulate them. But deeper thought helps us see the relationship more complexly. The complex relationship of things and humans isn’t just the province of philosophers; it’s also for artists and poets to explore in works that amuse and, in some cases, horrify.

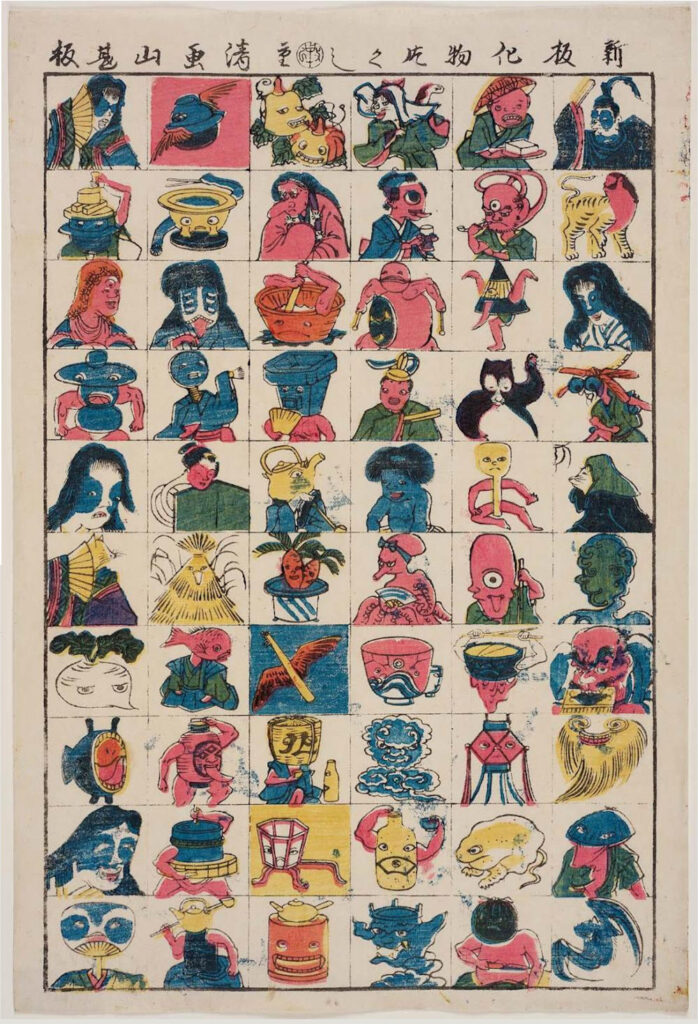

Folklore and old stories mark out some of the points of the relationship of things and humans. The lore of medieval Japanese Tsukumogami delight, as comically violent as they are, because they explore a world in which things acquire an identity—an energetic and human-like identity. The old Shinto versions tell of forsaken tools and utensils that become “ensouled” and take revenge on humans for throwing them away so carelessly. Things and humans become adversaries in the story, at times even deadly ones; yet, in order to sanctify the story for religious teaching, the ensouled old tools eventually achieve enlightenment.

The narrative follows a path of separation and estrangement finally redeemed. In the end, things ensouled and divinely blessed—attributes that traditionally only apply to humans—blur the distinctions of thing and human. All things (human, too) are united in enlightment, a signal of the animism that Shinto monks injected into old Japanese folk tales to make the stories into homilies.

Another narrative arc exploring things and humans in effect goes in the opposite direction. Rather than moving from degrading rejection and estrangement as in stories of the Tsukumogami, such stories depict the merger of things and humans (or, at least, personifications). They are inseparable, and identities dissolve into the things that, quite literally “make them up.” In the end, trying to discard a thing also diminishes the identity.

As with the Tsukumogami, there’s also a good deal of art that illustrates the relationship.

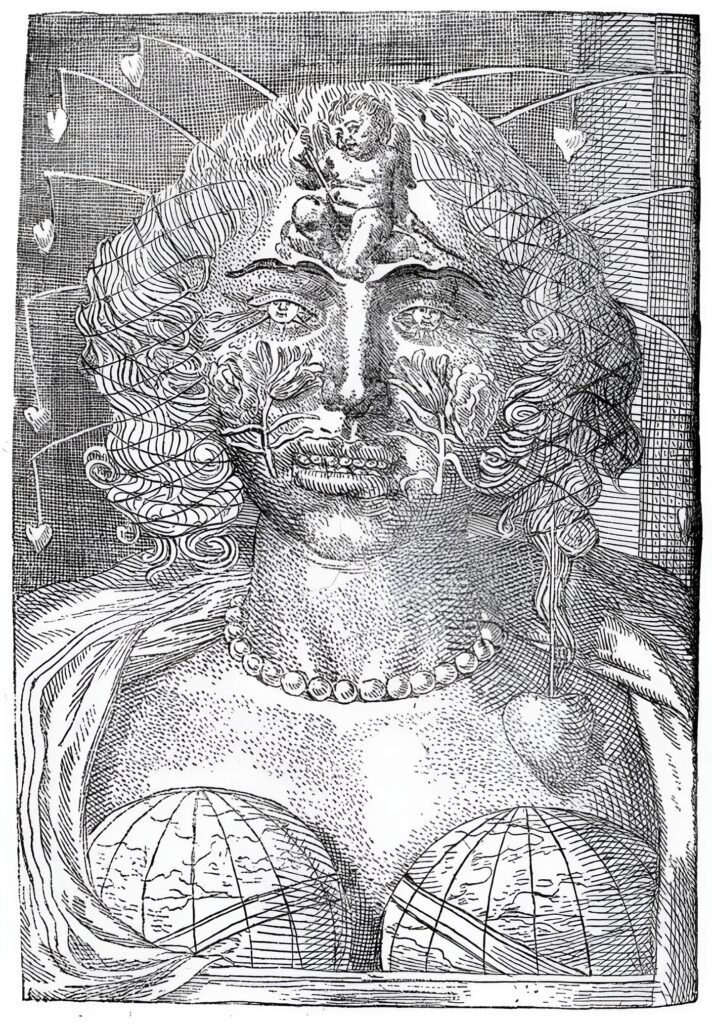

Taking things and creating human-like images from them—either in illustration or metaphor—emphasizes dependency of things and humans, even to the point of blurring the distinction between the human and the, er, vegetable, as Guiseppe Arcimboldo (1527–1593) did in several of his works, including Vertumnus (pictured, enlargement available here). Arcimboldo’s oozily porous relationship of human personification of the seasons and vegetation simply reverses the Shinto stories of Tsukumogami. Rather than separating old things from human shape, Arcimboldo’s painting inseparably unites them. Pick a fruit only at the expense of the portrait.

Taking things and creating human-like images from them—either in illustration or metaphor—emphasizes dependency of things and humans, even to the point of blurring the distinction between the human and the, er, vegetable, as Guiseppe Arcimboldo (1527–1593) did in several of his works, including Vertumnus (pictured, enlargement available here). Arcimboldo’s oozily porous relationship of human personification of the seasons and vegetation simply reverses the Shinto stories of Tsukumogami. Rather than separating old things from human shape, Arcimboldo’s painting inseparably unites them. Pick a fruit only at the expense of the portrait.

Arcimboldo may have painted the cornucopia in this weirdly human form to celebrate the Habsburg empire. (He was a court portraitist for emperors Ferdinand I, Maximilian II, and Rudolf II, and other aristocrats of his time.) Whatever his motivation, the image itself is whimsical. In the early twentieth century, Viktor Lindhar could have easily slapped Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus, the Roman god of seasons, on his best-selling and influential book that popularized the diet cliché “you are what you eat.” Arcimboldo’s work attracted the attention of such such twentieth-century Surrealists as Salvador Dalí, and through them re-entered art history.

This idealized overlap of things and humans appears in poetry, too, and predates Arcimboldo’s fruit-bowl portraits. Look at lines from Francesco Petrarca’s Sonnet 124 (“Quel sempre acerbo ed onorato giorno”):

Her locks were gold, her cheeks were breathing snow,

Her brows with ebon arch’d—bright stars her eyes,

Wherein Love nestled, thence his dart to aim:

Her teeth were pearls—the rose’s softest glow

Dwelt on that mouth, whence woke to speech grief’s sighs

Her tears were crystal—and her breath was flame.

Petrarca’s images link hair with gold, cheeks with snow, eyebrows with ebony, eyes with stars, teeth with pearls, lips with roses, tears with crystal. The associations appear in other of his poems as well, and they were imitated by other poets slavishly enough to become clichés. Of course, these can be dismissed as mere extravagant metaphor, among poet’s favorite tricks. With Petrarca and his imitators (especially in Elizabethan England) such constellations of metaphor (and extended metaphor at that) amount to what’s known as the “Petrarchan conceit.” Shakespeare mocked Petrarca’s tactic in his well known sonnet 130 by back-handed use of the metaphors. His sonnet works satirically:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damask’d, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

That Shakespeare chose to satirize Petrarchan conceit by deploying them (actually, turning them) emphasizes undesirable qualities of the metaphors. What would those black wires growing on her head actually call forth in the lover’s mind? Or this playful note: “And in some perfumes is there more delight / Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.” Pictorial artists picked up on the absurdity and the grotesque, too. An illustration from a 1654 edition of Charles Sorel’s (c. 1602-1674) The Extravagant Shepherd puts overwrought Petrarchan conceit to the test by rendering it literally. Hearts of lovers are caught on fishing poles jutting out from netted hair. The beloved’s teeth line up in weirdly rounded pearls. Breasts are globes, and eyes spurt arrows from shining suns. Eyebrows are bows. The title page of Sorel’s book calls the story an “anti-romance,” and in the etching it shows.

Satire and mockery often magnify distinctions and differences in order to point out the ludicrous or false. Shakespeare’s sonnet 130 and the illustrator of Sorel’s book distinguish their works—whether “anti-romance” or proclamation of love—by exceeding already exaggerated Petrarchan conceits and metaphor. They make the metaphors even more visible, turning conceits into grotesque realities.

These examples, of course, draw their power from love (or at least lust), and I think that origin humanizes even the grotesque mockery of Shakespeare and Sorel’s illustrator. Arcimboldo’s vegetable portraits also draw from nature, as do many of Petrarca’s metaphors. But Arcimboldo also did other portraits using made things and tools, and the effect is less whimsy and more threatening. Arcimboldo’s The Librarian uses things of the trade as pieces of the portrait, and his subject is human, not a personification as in the Vertumnus. In effect, tools of a profession and human identity are united in portraiture, and the picture lands differently. The use of books, feather-dusters, bookmarks and book chest keys (note the librarian’s glasses) seems to constrain the librarian’s identity, humorously but also inhumanly. K. C. Elhard claimed that “Arcimboldo’s joke [in The Librarian] may have targeted not those who love learning but rather materialistic book collectors more interested in acquiring books than in reading them.” And perhaps even more than that: his treatment of librarians as the things of their profession depicts a form of entrapment.

The turn from personified seasons to human occupations, which gave Arcimboldo’s portraits a more critical edge, became even more pronounced with Nicholas de Larmessin’s (1634-1694) series of Travestissements, published between 1690 and 1720. Larmessin’s series included dozens of Habits des métiers et professions, all of them mixing items associated with occupations and the people doing the jobs. Like Arcimboldo, Larmessin substitutes things for anatomical parts, but unlike him, the things ornament a recognizable human frame, with faces and hands and (usually) human legs. Things make up a costume, at least in part.

Take a look at Larmessin’s picture of the blacksmith, for instance. Recognizably human hands grasp tools of the trade; other tools dangle from an unseen belt. Horseshoes, one of his products, make up the frilly hem of the blacksmith’s breeches. But horseshoes also dangle like curls from his head, replacing hair. The man’s forehead is an anvil—hard headed, he is—and a blacksmith’s furnace, complete with bellows and blazing fire, replaces his entire torso. Remove this poor man’s costume and he would be much diminished.

Larmessin’s etchings were issued under various titles, but one fits particularly well: Les costumes grotesques et les métiers. The images are indeed grotesque even as they are also amusements. They depict the merger of the things of occupations and trades with a human identity. (Other examples of Larmessin’s costumes grotesques can be seen at the British Museum website.)

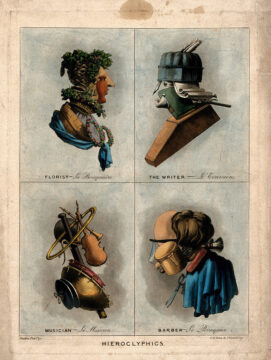

The mixing of tools and human image has continued. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, S. W. Fores issued a series of watercolor aquatints that harken back to Arcimboldo’s original portraits. Profiles composed completely of tools associated with occupations, they are labelled “Acrimboldesques” in the Wellcome Collection catalogue. Like Arcimboldo’s The Librarian, the profiles are cartoons and express an amusing “Arcimboldesque” whimsy. The barber, you will note, is quite bald. The title “Hieroglyphics” is interesting, and Public Domain Review takes note of it: “the title seems strange in relation to our current understanding of the word as denoting a system of writing in which pictures are used instead of words. In the case of the … image, it as though the act of replacement itself is enough, be it a word or a swathe of face, it does not matter — the whole world seen as renderable in a landscape of objects.”

Artist Viktor Koen teaches the School of Visual Art in New York, where he is Chair of the BFA Illustration and BFA Comics departments. It’s likely that you’ve seen his work in the New York Times, Esquire, WIRED, on the BBC, movie posters, book and record covers. His striking composites resonate with Arcimboldo and Larmessin, but Koen turns up the volume on the grotesque in photographic clarity. Whimsy comes from steampunk style present in many of his pieces. While earlier artists’ satires and grotesques may have an underlying social critique, Koen asserts his critique boldly, often uncomfortably so.

Commenting on his Bestiary: Bizarre Myths & Chimerical Fantasies (2015), Koen said in an interview, “The creation of hybrid prototypes reflects the complex and confusing dualities that mortals were dealing with. And things haven’t changed, we remain flawed and wonderful, strong and addicted, compassionate and greedy. We remain monsters and heroes as these mythical prototypes only illustrate our complex psychoses, passions and violent flaws just like biblical parables do.” Exploring the “hybrid” of experience is close to the center of Koen’s art.

“Carnivore 2” is one of a pair of profiles that illustrate the merger of thing and human. Carnivore 1 and Carnivore 2 appeared on facing pages in a collection of images gathered by George Petros and Les Barany called Carnivora: The Dark Art of Automobiles (2007) which served either as an exhibition catalogue or as a commemoration of one. The pair of illustrations have also been displayed together, as if in conversation, in exhibitions in Athens and London.

In “Carnivore 2,” Koen merges the human with the mechanical, especially parts from cars and motorcycles—the distinctive front end of a classic Jaguar E-type replacing a man’s forehead, nose, and eyes (headlights, of course). Contraption-y parts dangle from his head and neck, which is distinguishable as a human male only by remnants: an ear, short-cut hair, lips, and chin. The overall effect is violent, underscored by blood-like stains emanating from the front of the face, as if sprayed and scattered by a headwind.

The image, like many of Koen’s illustrations, is ominous and warns of a mechanization of humanity, the replacement of human “parts” by metal and wires. In Koen’s “Carnivore” pair, the car becomes an instrument of darkness and encroachment.

For the bibliographically curious: Interesting and well illustrated article relating Arcimboldo and Dalí, by ophthamologists at SUNY and curators of the Dalí Museum: Martinez-Conde, Susana, Dave Conley, Hank Hine, Joan Kropf, Peter Tush, Andrea Ayala, and Stephen L. Macknik. “Marvels of Illusion: Illusion and Perception in the Art of Salvador Dali.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9 (September 29, 2015). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00496. Interpreting Arcimboldo’s The Librarian: Elhard, K. C. “Reopening the Book on Arcimboldo’s Librarian.” Libraries & the Cultural Record 40, no. 2 (2005): 115–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/lac.2005.0027. A collection of Koen’s images from his Bestiary appear in a good interview: “ Viktor Koen: An Interview on Myths, Innocence & Darkness.” Lomography. https://www.lomography.com/magazine/327434-viktor-koen-an-interview-on-myths-innocence-darkness. Also in Hernandez, Ciel. “The Dark Pantheon & Peculiarities: Viktor Koen.” Lomography, January 30, 2017. https://www.lomography.com/magazine/326905-the-dark-pantheon-peculiarities-viktor-koen.

Image credits: Shigekiyo, Utagawa. A New Collection of Monsters (Shinpan Bakemono Zukushi) [新板化物つくし]. Woodblock print; ink and color on paper, 36.8 x 24.9cm. Maruya Jinpachi, 1860. MFA; http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/a-new-collection-of-monsters-shinpan-bakemono-zukushi-190862. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tsukukogami-Bakemono-Print-Shigekiyo.jpg. Rights: Public domain.

Arcimboldo, Guiseppe. Vertumnus. 1591. Oil on panel, height: 700 mm (27.55 in); width: 580 mm (22.83 in). Skokloster Castle. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vertumnus_%C3%A5rstidernas_gud_m%C3%A5lad_av_Giuseppe_Arcimboldo_1591_-_Skoklosters_slott_-_91503.jpg. Rights: Public domain.