by Rafiq Kathwari

As Fareed drove in soft rain through red lights to Maimonides, my sister-in-law Farrah, and I sat in the back seat of the sky-blue Volkswagen van.

“Kicking,” she said, placing my hand on her round belly. Shy, I gazed at her polished toes in flip-flops.

A stork dropped a boy in Brooklyn eight years to the day JFK was slain in Dallas. New alien in New York, I babysat my curly-haired nephew in a stark rental on Park Avenue where the doorman first thought of us as the move-in guys, and where our Numdha rugs, hand-made in Kashmir, screamed to come out of our walk-in closets.

“Make money fast carpeting America from sea to shining sea,” grandfather had penned in an aerogram. Fareed rode the subway to Pine Street; Farrah was a cashier at Korvettes. The boy and I together discovered Big Bird on a Zenith console, my first TV exposure at age 22.

I watched the boy dunk hoops in purturbia, his long hair swishing to Metallica’s “Disposable Heroes.” He enrolled in the local chapter of the National Rifle Association, his dad’s rifle slung across the boy’s shoulder to hunt jackrabbits upstate.

He climbed a peak one summer in Kashmir, a paradise in pathos, a heated topic at our dinner table, but on the periphery of America’s mind, rarely mentioned on the Evening News, never on “All in the Family,” a popular sitcom that dared to shake America’s somnolence even as B-52 bombers rained napalm on Vietnam, fueling our rage.

In our hearts we knew we had to do what we could with what we had to help untie the Gordian knot of the Kashmir dispute, never again to let mad men tear apart husbands from wives, siblings from siblings, sons and daughters from mothers and fathers across the Line of Control since 1947 when India divided herself.

I can imagine how our family history seized my nephew’s receptive mind as he and his mates chilled every Sunday at the Islamic Cultural Center on California Road in Eastchester, once a Greek Orthodox Church, now embraced as a house of worship by a fresh wave of immigrants anxiously learning new ways of seeing and thinking.

Eager to impart their native cultural heritage to American-born kids, parents seemed unconcerned as weekday shop owners moonlighted as Sunday school teachers who were seemingly unable to equate the paradox of America’s ample prosperity at home with its wanton militarism abroad. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023. The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

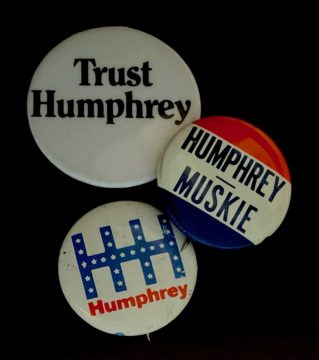

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons. I teach at a large, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For about a decade now, the upper administration has had a habit of sending “comforting” emails whenever there’s a major school shooting. Of course there are far too many school shootings in America to send a note for each one, so I suppose the administration tries to keep it “relevant,” for lack of a better word. These heartfelt missives arrive in my Inbox once or twice a year, typically after some lunatic shoots up a college campus. So far as I can tell, they go to everyone. To every faculty member, staff member, and student on campus. To 25,000 people or more.

I teach at a large, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For about a decade now, the upper administration has had a habit of sending “comforting” emails whenever there’s a major school shooting. Of course there are far too many school shootings in America to send a note for each one, so I suppose the administration tries to keep it “relevant,” for lack of a better word. These heartfelt missives arrive in my Inbox once or twice a year, typically after some lunatic shoots up a college campus. So far as I can tell, they go to everyone. To every faculty member, staff member, and student on campus. To 25,000 people or more.