by Carol A Westbrook

It all began about 4.5 billion years ago, give or take a few millennia. The earth was still young, having been formed by the accretion of material that orbited around the sun. It was a young, moderate-sized planet, and, like the other planets in the solar system, it spun like a top as it rotated around the sun, with an axis that was parallel to the sun’s rotational axis. This configuration was the most stable for the planets in the solar system, though today only Mercury and Jupiter still have an axis that is parallel to the sun’s.

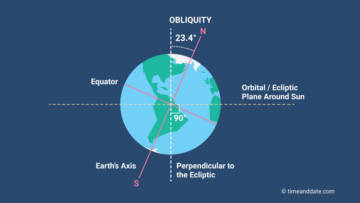

On that day, 4.5 billion years ago, an erratic planet about the size of Mars, called Theia, came crashing through the solar system and collided with the young Earth. This was not the same collision that killed most of the dinosaurs, which happened about 66 million years ago. The collision of the two planets resulted in the formation of the moon. But there was another significant result of this collision – the Earth’s axis shifted, from a position parallel to the sun’s, to one that is off by 23°! This tilt is the reason we have seasons.

The change in the earth’s axis away from parallel to the sun means that during the year, with Earth’s rotation around the Sun, the northern hemisphere will be pointing toward the Sun for about half the year, warming the earth and giving us summer. In the other half of the year it will be pointing away from the Sun, giving us cooler temperatures, or winter. The transitional seasons, spring and fall, are accompanied by more neutral temperatures.

Now, fast forward 4.8 billion years. No longer hunter-gatherers, humans now live a more settled existence. With it came civilization. They became more settled, relying heavily on agriculture and animal husbandry for sustenance. Farmers looked for reproducible patterns to help their ventures succeed. It was important to know when spring would arrive; when was lambing season; when were the rains going to start, and so on. They relied on their priests and holy men to give them this information, and priests used calendars derived from astronomy to make their predictions.

Often large, complex monuments were built to help follow the movement of the sun and predict the important days in the calendar. The most familiar, and elaborate, of such monuments is Stonehenge, located on the Salisbury plain near the town of Wiltshire. Stonehenge was built between 3000 and 1520 BCE during the transition from the Neolithic Period (New Stone Age) to the Bronze Age. There are no written “directions’ for the interpretation of the stone circle, but it has been studied since the 1600’s and various theories have been advanced, The most recent theory, and the one that is deemed to closest to the true function, is that Stonehenge points to the solstices.

In the New World we find Cahokia, an ancient culture and city, now an archeological site near modern St. Louis that reveals much about the North American Indigenous history. Among the mounds of Cahokia is the monument called “Wood Henge” , which lies south of Chicago, near St. Louis. Radiocarbon dating has provided a date of 3,000 BCCE, so it is contemporary with Stonehenge and very similar in construction, though it is made of wood instead of stone.

Finally, the archeological site of Chicheni Itza, on the Yucatan peninsula, is a tourist attraction for its many temples and sacrificial sites. The main temple, El Castillo, also known as the Temple of Kukulcan is a Mesoamerican step-pyramid that dominates the center of the Chichen Itza archaeological site. Around the Spring and Autumn equinoxes, in the late afternoon, the northwest corner of the pyramid casts a series of triangular shadows against the western balustrade on the north side that evokes the appearance of a serpent wriggling down the staircase, which some scholars have suggested is a representation of the feathered-serpent deity, Kukulcán. Its appearance signals the solstice.

The solstice is one of the most useful dates, and easiest to predict. The word solstice is derived from the Latin sol (“sun”) and sistere (“to stand still”), because at the solstices, the Sun’s declination appears to do just that, to “stand still.” When viewed from the ground, the sun moves daily further south (or north), but reaches a stopping point and begins its journey back. In the northern hemisphere, where most of us live, the solstice represents the shortest day (and longest night) of the year. It marks the “return of the light.” In other words, the dark of winter is over and spring will be here soon. Solstice is a time for celebration and rejoicing. Many religions had a celebration on the winter solstice, but the Roman Catholic Church initially did not.

Finally, written calendars came into general use and the date of a feast day could be accurately specified. The Hebrew calendar, for example, is based on lunar cycles, but requires “leap months” to keep in phase. The Catholic Church wanted Christmas to fall on the winter solstice, which should have been on December 25th. In the early 330’s, Pope Julius I declared December 25 to be the birthday of Jesus Christ.

The Church had a good reason to pick this date, as it is the day of the winter solstice, and the feast of Saturnalia! This is a very popular time of celebration, Because of when the holiday occurred—near the winter solstice—Saturnalia celebrations are the source of many of the traditions we now associate with Christmas, such as wreaths, candles, feasting and gift-giving. Celebrating Christmas on this date helped the Romans accept Christianity as their religion.