by David Oates

Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

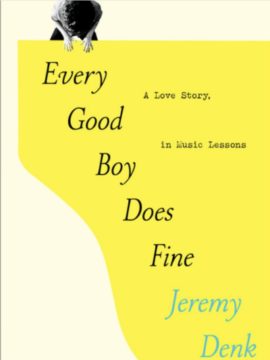

I sat in a corner where I could see but hardly be seen. My book on this day was Jeremy Denk’s recent memoir Every Good Boy Does Fine. My what a writer. And what a pianist! I was having a lot of fun, in my bookish way.

It led to a surprising interaction, a brief conversation about art and music with the young woman clearing and wiping the little café table next to mine. Pretty, with long dark hair. Friendly and open – “What are you reading,” she surprised me, but in a good way. I showed her the cover, explained about my amateur piano-playing, Denk’s twofold talent. She responded with an anecdote about Salvador Dali. And that, with smiles, was our interaction. Two humans, two minutes.

I spend a lot of time on my own, and I’m happy that way. But sometimes I really feel kindness when it is offered. A smile, a word. And it surprises me how much warmth that can create.

Then she cleared the wee table two over from me, where two possibly homeless gray-haired people had been sitting. A man and a woman, some kind of couple; they were given breakfast plates involving big waffles. I wondered if these were “comped” by the staff. No way to know, and I shouldn’t guess. They were so alike, this couple, they could have been twins: both diminutive, with neat active bodies and excellent long hair woven under practical caps or hair-bands above weathered faces. Impossible to age: Forty? Seventy? A few hundred?

But the man soon ramped up into a loud ranting voice, declaiming violently to or at his apparent partner. She sat motionlessly, strategically I thought: as if she knew which words would come to nothing, which to blows.

In a few minutes he simmered down and they stood up to leave, bussing their table like well-trained bourgie customers. They were full of contradictions.

On the café sound system some cool jazz. It was a big space with a high ceiling. I looked at the internet, got drawn into another excited report on the Webb deepspace telescope. A yellow pad, entirely blank, waiting for my input. Some birds in the window, fluttering and then darting off.

Reader, isn’t every day is some version of this? – a crazy mélange of inward moments and outward interruptions, good luck and ill will, coarseness and surprise breakthroughs into insight or even grace? When we stratify experience into high and low, we falsify it. For it all comes jumbled together. How subtle the art is to capture that. To get that texture into the text.

How Bach did it. How I might do it.

* * *

I’m at liberty to notice such things, to be idle and unoccupied enough to catch it as it passes. I’ve arranged my whole life for this freedom.

And now, in my gray years, time has spread before me like a beach at lowest tide. There’s a quietness about it, a comforting gray overcast. A contemplativeness. We’ve brought ourselves to New Mexico for our annual tradition, a nice long working vacation. My partner photographs, sketches, plans his next move as an artist. I read and write, of course. This high desert speaks to us, so full of emptiness and excellence.

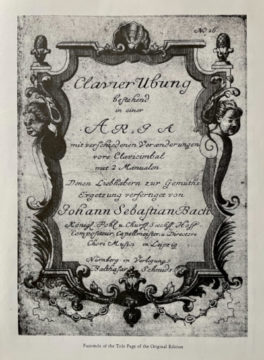

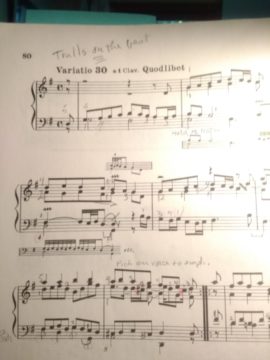

And that’s what I’m thinking about as I listen for the umpteenth time to Bach’s Goldberg Variations, specifically to the last one, the thirtieth, which is titled “Quodlibet,” and which makes absolute mockery of all the highfalutin critical rhapsodies about these variations.

And that’s what I’m thinking about as I listen for the umpteenth time to Bach’s Goldberg Variations, specifically to the last one, the thirtieth, which is titled “Quodlibet,” and which makes absolute mockery of all the highfalutin critical rhapsodies about these variations.

For the title means roughly “Whatever you want,” and the contents – well, Bach sees fit to grab two lowbrow tunes from taverns and fashion them into a bright, cheery, overlapping polyphony. One is called “Cabbage and Beets”! And the other’s name hasn’t survived. They’re popular songs, maybe drinking songs, certainly vulgar, probably smutty. And yet to me they sound as redeeming and full of life as anything in the whole seventy minutes of the Variations.

* * *

Webster’s Dictionary gives the word this way:

quod·li·bet | \ ˈkwäd-lə-ˌbet \

1: a philosophical or theological point proposed for disputation also : a disputation on such a point

2: a whimsical combination of familiar melodies or texts

(Middle English, from Medieval Latin quodlibetum, from Latin quodlibet, neuter of quilibet any whatever, from qui who, what + libet it pleases, from libēre to please)

What I like best in music is the way it makes many things simultaneous, happening in their separate ways but adding up to a now of richness, complexity, depth. Like looking through a pool of water, surface and depth and fish coasting through. (The bottom “pebbly with stars,” as Thoreau says.)

In this way Bach or Palestrina or Pärt or any good jazz combo offer a model of the mind, a way of thinking that is the opposite of fundamentalism and literalism or any false certainty that reduces life to a code, a creed, a law, a grievance, a self-justification.

The alternative is working out your salvation in the fear and trembling that knows life is too deep and strange to ever be reduced. It’s all levels, or none. That is a mystery that ought to keep all of us humble. And which might make music a better creed than any credo.

* * *

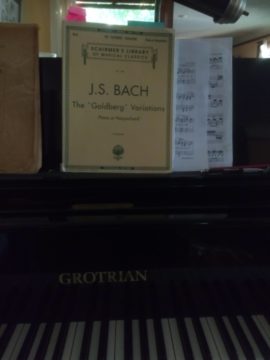

Whenever I open up my Schirmer edition of the Goldberg Variations to play a few of them, I page past this epigram chosen by the modern editor Ralph Kirkpatrick:

Whenever I open up my Schirmer edition of the Goldberg Variations to play a few of them, I page past this epigram chosen by the modern editor Ralph Kirkpatrick:

“There is something in it of Divinity more than the ear discovers: it is an Hieroglyphical and shadowed lesson of the whole World, and creatures of God; such a melody to the ear, as the whole World, well understood, would afford the understanding. In short it is a sensible fit of that harmony which intellectually sounds in the ears of God.”

– Sir Thomas Browne: “Religio Medici” (1643)

Often I nod at the aptness of these admiring words – even if the Goldbergs were not to be published for another hundred years (1741) after Browne wrote. I think many of us feel something like a religious awe in the music of Bach. Fugue or concerto grosso, little gigue or elaborate chorale: it’s where the whole world makes sense. At least briefly. Before we return to the many-miseried jumble of life.

Sir Thomas Browne is a seventeenth-century English prose writer, author of the (today) nearly unreadable Religio Medici, a learned defense and examination of his own religious beliefs. For he was of that generation that saw England overtaken by an army of fundamentalist Christians led by the famed general Oliver Cromwell. Just six years after Browne’s self-exploration, the pious had struck off the head of Charles the First and installed Cromwell as king-by-a-different-title. Meanwhile they famously closed the theaters, though not quite shutting down the pubs (in those days the fundies drank as much as the unsaved). They even mistrusted music – trying to purify the church of that, too. Too fancy, too learned.

It’s so much easier to hate and be certain than to sing and be moved.

So. . . Browne’s times a bit like our own: who can forget the Jesus banners waving at the head of that mob beating down the Capitol police, smearing feces and breaking windows as they sought to lynch those who were only democratically elect. Many of these rioters were self-described “Evangelicals.” How they loved to feel empowered to rage against immigrants, people of color, and whoever dared to be educated or professional!

It’s worth remembering that Cromwell’s mad and deadly followers were of that exact slice of Protestant enthusiast who had also sent a few ships of purists to settle in the New World – our word “Puritan” masking the a-bit-too-on-the-nose fundamentalist. But that’s who they were.

So, here in this epigram is Bach’s music seemingly placed into the actual moil and misery, then and now. The meaning of sixteen-forty-something not so different from the meaning of two-thousand-twenty-something. Struggle, disappointment. The human condition.

Of course Browne himself cannot be referring to Bach – it’s just some later editors who have created this connection. So what was Browne actually referring to? Here’s his lead-in:

“Whosoever is harmonically composed delights in harmony; which makes me much distrust the symmetry of those heads which declaim against all church-music. For myself . . . I do embrace it: for even that vulgar and tavern-music, which makes one man merry, another mad, strikes in me a deep fit of devotion, and a profound contemplation of the First Composer.”

Even tavern-music. Think of that. As if the whole world did make sense, the songs of drunkards, the fugues of savants, the hymns of saints. As if it were all, after all, beautiful.

* * *

The Goldberg Variations is a set of thirty-two compositional fancies all following the same harmonic pattern, a theme especially audible in the base and introduced in the opening (and identical closing) Aria. Out of his apparently boundless inventiveness Bach plays and inverts and subverts and in general treats this pattern as his sandbox – his inspiration – his beloved – his plaything. A world of emotion: ecstatic, despondent, questioning, affirming. If you listen right through, you’ll feel it all.

And more. The high and the low, the mournful and the ebullient. A shift to minor key so brooding it’s known as “the black pearl.” In an National Public Radio conversation, Denk play-mocks the Goldbergs as everything including “the kitchen sink.” Instead of the simple hierarchy of harmony – melody at the top, supporting chords underneath – in Bach there’s the restless democracy of polyphony: every line an equal voice, singing a separate tune. Two voices, three, four. Yet all working together. Perhaps the lines swap around the emphasis – my piano teacher demands that I choose which line to make sing out. . . but soon that line will be supplanted by another taking its turn. The voices surge along with each other like dolphins, one appearing and then another. Exuberance and equality: it’s the musical equivalent of e pluribus unum.

But the Latin we ought to be invoking here is the euphonious concordia discors: “discordant harmony.” It’s quite an old insight:

The doctrine of concordia discors – the idea that the numerous conflicts between the four elements in nature (air, earth, fire and water) paradoxically create an overall harmony in the world – can be traced back to the Greek philosophers. . . .The Latin phrase which is used to encapsulate the idea was first used by Horace in the twelfth epistle of his first book (c. 20 B.C.) to describe Empedocles’ philosophy that the world is explained and shaped by a perpetual strife between the four elements, ordered by love into a jarring unity, or, as the musical metaphor held it, a “discordant harmony”.

And I absolutely love that the learned phrase can be reversed, and often is, without loss of its meaning. Discordia concors, if you wish.

I learned about it in a graduate classroom exploring Alexander Pope’s 1713 poem “Windsor-Forest.” It stood out for me because, as a young would-be nature poet myself, I felt for once at home in the otherwise too-formal poetry of this powdered-wig era. The lines were iambic pentameter in rhymed couplets, but what they were getting at felt like my home truth.

Here Hills and Vales, the Woodland and the Plain,

Here Earth and Water seem to strive again,

Not Chaos-like together crush’d and bruis’d,

But as the World, harmoniously confus’d.

(II. 11-14)

Harmonious confusion! What optimism I felt in those words! For in my twenties my life was a shambles of unharmonized pieces. The years themselves were broken in two, nine months of grad school followed by three months in the Sierra Nevadas, climbing and guiding troubled boys into wild adventures. To get this craziness into my plodding life meant connecting by a cross-country drive much like the one my partner and I will retrace later this month to get home to Portland. For summers I went from Atlanta (Emory University) to Los Angeles, and then back again – in those days executed as fierce solos, nonstop except for exhausted naps in the desert somewhere near Albuquerque. I was loveless, solitary, and unable to find any connection between heart and head, belief and necessity, lust and honor, truth and faith, mountains and libraries.

To Pope’s touching nature descriptions I added poetry from Gerard Manly Hopkins (no one could read my heart like those earnest Victorians!) – in a poem which I, like many others, could do by heart:

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough. . .

That’s “Pied Beauty” of course. I assure you I was reciting it as I pulled a little pan-sized cutthroat trout out a high-mountain stream, or rejoiced on polished granite beside a glacial lake as I reeled in astonishingly over-decorated brookies – black spots and red spots and yellow spots displayed against halos of blue, against bodies of olive green. Black and white and crimson contrasts tipping the fins. Rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim.

If I had no theory that could make sense of all this – no benevolent divinity or heart of faith, since I had dragged myself out of evangelicalism – that was okay, as long as I could experience it.

* * *

In my edition of the Goldbergs, Kirkpatrick offers a detailed introduction. “The Quodlibet mixes together the tunes of two folk-songs”:

In my edition of the Goldbergs, Kirkpatrick offers a detailed introduction. “The Quodlibet mixes together the tunes of two folk-songs”:

“Ich bin so lang nich bei dir g’west.

Ruck her, ruck her, ruck her.”

translated as:

“I’ve not been with you for so long.

Come closer, closer, closer.”

and the second tune:

“Kraut und Rüben haben mich vertrieben.

Hätt, mein’ Mutter Fleisch gekocht,

so wär ich länger blieben.”“[Cabbage and beets] drove me far away.

Had my mother cooked some meat,

then I’d have stayed much longer.”

My German dictionary reveals that “Kraut und Rüben” is a proverbial way to say something like all mixed up or perhaps higgledy-piggledy. Surely part of the ongoingness of life is the way it throws everything at you, in no particular order. “One damn thing after another,” with none of the tragic unity we might see on stage or in novels.

Bach’s first biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel offers a vivid picture of the annual Bach family reunions, where rowdy sing-alongs were a regular feature:

“…as soon as they were assembled a chorale was first struck up. From this devout beginning they proceeded to jokes which were frequently in strong contrast. That is, they then sang popular songs, partly of comic and also partly of indecent content, all mixed together on the spur of the moment. . . . This kind of improvised harmonizing they called a Quodlibet.”

And sure enough, when Kirkpatrick digs a little deeper into the songs of the Goldberg’s Quodlibet he quickly sees lewd but hard-to-translate implications. Turgid this, moist that. It’s quite a leap from the solemn pieties of good clean polyphony, isn’t it!

So. Bach’s Quodlibet is a way of concluding his high-flying exploration, with its thirty spiritual and mathematical ecstasies (and two Arias), by grounding it solidly in everyday reality. Bringing it down a few notches. Answering the highfalutin with. . . cabbage, darling.

* * *

The word quodlibet is often translated a little archaically, as “Do What Thou Wilt.” This phrase was made famous in the Rabelais fantasy Gargantua and Pantagruel (1530-64) as words written over the doorway of the Abbeye de Thélème. In French: “Fay ce que voudras.” The scholar Graham John Wheeler sums it up for us:

Rather than being governed by a monastic rule, the inhabitants of the Abbey rule themselves. The following famous description appears in Chapter 57: All their life was spent not in laws, statutes, or rules, but according to their own free will and pleasure. . . .

“DO WHAT THOU WILT, because men that are free, well-born, well-bred, and conversant in honest companies, have naturally an instinct and spur that prompteth them unto virtuous actions, and withdraws them from vice, which is called honour.”

Such liberty could only lead to scandals. . . or breakthroughs. Wheeler notes that William Blake wrote: “Do what you will this Lifes a Fiction And is made up of Contradiction.” And that Aldous Huxley published an anthology of essays titled Do What You Will (1928). Actually there’s no end of it, once the door of liberty is opened.

And what is a Christian to do with, for instance, the famed “liberty of Christ”? The law of love that replaces rulebook religiosity. In my Baptist travails I knew the verse where Paul asserted “For all things are lawful for me, but not all things are edifying.” I wondered what scalpel could help me divide these things. In a church that was considerably less full of liberty than this.

Rabelais’s Abbey of Theleme has left a word in English, connected with much naughtiness: Thelemic.

from the Greek word thelema, will.

Rabelais’ ideas were distorted by the notorious Hell-fire Club of the eighteenth century, founded by Sir Francis Dashwood at the former Cistercian abbey at Medmenham, on the banks of the Thames near Marlow. Rabelais’ motto was placed over the entrance, but the members indulged themselves not with virtuous actions but with obscene parodies of the rites of the Christian religion. The word was taken up in the early twentieth century by the occultist Aleister Crowley in reference to what he called his “thelemic power-zones”.

* * *

On our long journey from New Mexico back to Portland, we choose CDs to beguile the time, and into the slot I slip the famous Glenn Gould recording of the Goldbergs. That is, the first of his two recordings. This is the 1955 version performed at breakneck speed, impossible speed – which announced him as a young keyboard wizard. (Twenty-six years later he would record the Goldbergs again. But this time he made a recording of eccentrically, perhaps bizarrely slow tempo.)

In the passenger seat I read along in Denk, who proposes that the secret of Bach’s music is its “ongoingness,” as if it wants to never stop. In this it resembles “God’s eternal plan, the spinning cosmos.” I remind myself, for later: try to play it this way. Like inevitability, endless. Like this landscape.

The miles roll by, Colorado, Utah. . . hills mount up chalk white and sandstone red, mesas nearby and flattop ridges all the way to the horizon. The cataclysms of the past, silently bearing the bones of dinosaurs into their next eons.

News of the Queen’s passing reaches us as we roar down the Interstate.

We learn the new king will be another Charles, third of this name to rule the island.

* * *

Glenns Ferry appears as an oasis below the highway: wide blue-green river, trees, farmlands, streets and drive-ins. Green is the color of pathos in this country, suggesting life and desire and possibility. We pass “Three Island Crossing State Park,” which all by itself suggests a little historical novel. Later I look it up:

Oregon Trail pioneers knew Three Island Crossing well. . . . Upon reaching the Three Island Ford, the emigrants had a difficult decision to make. Should they risk the dangerous crossing of the Snake, or endure the dry, rocky route along the south bank of the river? About half of the emigrants chose to attempt the crossing by using the gravel bars that extended across the river. Not all were successful; many casualties are recounted in pioneer diaries. The rewards of a successful crossing were a shorter route, more potable water and better feed for the stock.

The Three Island Ford was used by pioneer travelers until 1869, when Gus Glenn constructed a ferry about two miles upstream. Some travelers continued to cross at Three Island to avoid paying for the ferry.

A ferry, a ferryman to be paid. A strange world awaiting beyond the river. If the story hasn’t been told yet, it should be.

* * *

The Webb Telescope out there every second of the rest of our lives, as the world bakes and we kill each other and half the species on the planet: here’s a chance to watch the stars and listen for the still small voice and do the right thing. Everything won’t stop being beautiful if we don’t. But we’ll have missed an opportunity.

Quodlibet is liberty, the freedom we can never escape. And the chance – the possibility – of finding it beautiful. Making it beautiful.

When you look at the jumbling together of high and low – using these rowdy rounds to conclude the Variations. . . the question of what is elevated and what is base is turned into a non-question: it’s all fair game, high and low. As if we really did live in this mixed kettle of fish, where spiritual thoughts are interrupted by stomach-rumbles (or worse! way worse!) every single day of our lives – our appetitive, spiritual, horny, intellectual, delicately-coarse/coarsely-delicate lives.

“There is no great beauty without some strangeness,” said Francis Bacon. And this is the strange beauty of our mixed-up life. Not classic beauty: surprising beauty.

Everywhere beauty.

* * *

EPILOGUE: A few Goldberg Variations performances to sample:

Ralph Kirkpatrick (harpsichord, 1959: old-school, cool and direct)

Robert Hill (2015 – harpsichord, 2015: opens with a Baroque-inspired improvisation, on a sonically gorgeous instrument)

Jeremy Denk (piano)

Kimiko Ishizaka (piano: I like it, though maybe a little dry)

Murray Perahia (piano: somewhat faster)

Fanny Vicens (accordion!)

PADAM Singers (vocal + instrumental)

Norwegian Chamber Orchestra (Jazzy! Fully swinging, with a big plucked double bass and all.)