by Eric Bies

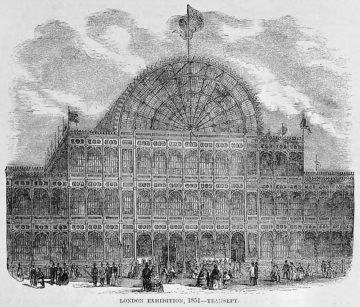

May of 1851, London, the world’s first World’s Fair.

May of 1851, London, the world’s first World’s Fair.

Just about Anyone who was (or was bound to be) Anyone was in attendance at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations—a mouthful—among them: Charles Babbage, Charles Darwin, and Charles Dickens; Charlotte Brontë, Lewis Carroll, and George Eliot; Karl Marx, William Morris, and Alfred Tennyson; Tolstoy (a playboy, beardless and boyish) and Flaubert (accompanied by his mother).

If we were there we could have followed them: down the paths and over the lawns—beneath the little boys perched in the trees—thousands of visitors, many of whom had patronized this stretch of Hyde Park in the past, now encountered a new kind of structure rising from the green. Taking it all in, the word “magnificent” sprang to mind; in a chorus they called it the Crystal Palace—and no wonder, with its million square feet of floor space and monumental façade of leaping glass and iron.

What all went inside? Apart from the full-grown trees and gallant blocks of statuary, a quick glance at a single page of the Exhibition’s Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue instantly gluts the eye. This taxonomical mountain of close-set type, ranging over 3,000 pages in four volumes, threatens an avalanche of things: a portable steam engine, a hydraulic seed press, a pedestal planisphere, a bath of enameled copper, Irish bog-yew furniture, a triform railway signal, crystals of sulfate of iron, an overshot water-wheel, a hydraulic lifting jack, a low-bodied dog cart, a self-acting duplex lathe, an India-rubber air-gun, a liquid manure cart, a sheep-dipping apparatus, bar and frame beehives, an imitation oak timepiece, a black marble timepiece, a couch designed for invalids, a salinometer, an electric telegraph, racing whips, a pyro-pneumatic stove-grate, ornamented fire-dogs, a copper coal-scuttle, vulcanized valve-cocks, an Etruscan tea-urn, serpentine obelisks, a battle-ax, a shield of deer-skin, a bark canoe, a scale model of the steam-ship Medea—and much, much more.

What all went inside? Apart from the full-grown trees and gallant blocks of statuary, a quick glance at a single page of the Exhibition’s Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue instantly gluts the eye. This taxonomical mountain of close-set type, ranging over 3,000 pages in four volumes, threatens an avalanche of things: a portable steam engine, a hydraulic seed press, a pedestal planisphere, a bath of enameled copper, Irish bog-yew furniture, a triform railway signal, crystals of sulfate of iron, an overshot water-wheel, a hydraulic lifting jack, a low-bodied dog cart, a self-acting duplex lathe, an India-rubber air-gun, a liquid manure cart, a sheep-dipping apparatus, bar and frame beehives, an imitation oak timepiece, a black marble timepiece, a couch designed for invalids, a salinometer, an electric telegraph, racing whips, a pyro-pneumatic stove-grate, ornamented fire-dogs, a copper coal-scuttle, vulcanized valve-cocks, an Etruscan tea-urn, serpentine obelisks, a battle-ax, a shield of deer-skin, a bark canoe, a scale model of the steam-ship Medea—and much, much more.

Of course, such a spectacle came with its detractors. Take Thomas Carlyle, who mocked the structure’s crystalline shimmer for its resemblance to the sudsy substance of a soap bubble. Or John Ruskin, who, having just published the first volume of The Stones of Venice, shrank from the sheer quantity of artless glass. Or, yet, Fyodor Dostoevsky: touring London a decade later, he took one look at the polished sprawl (which, meanwhile, had been torn down and rebuilt on the other side of the Thames) and stuck out his tongue.

The building’s chief architect, Joseph Paxton, was not an architect by training. He was a gardener. And though Victoria’s England could not quite call itself the Quattrocento, the era remained capable of embracing a polymath spirit (the nineteenth being perhaps the last century to do so). A handful of figures from the period meet the description; few are as readily granted membership to that class of Copernican minds, restless and ingenious in equal measure, as Paxton, the man Charles Dickens dubbed “the busiest in England.”

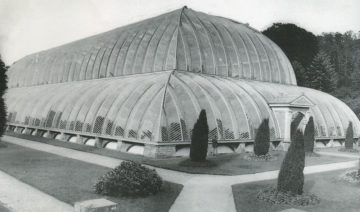

Recognized as the head gardener for the 6th Duke of Devonshire, he had made his name overseeing the vast estates at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, quick to render the place a notable tourist destination for the surpassing beauty of its grounds. For Paxton, no request, no challenge, from the Duke would go unanswered. Project by project, the necessity of excellence prompted not only the design of sublime landscapes and intricate waterworks but some of the first modern greenhouses. His innovative use of glass and iron in particular, manifested in the invention of a ridge-and-furrow roof, supplied a novel solution to the ongoing question of preservation—neither a new question, nor one for which the existing solutions had advanced much further than those at hand at the time of the Crucifixion, when Tiberian horticulturists contrived sheets of mica to shelter the Roman Empire’s first oranges. In Paxton’s case, the question came down to comparable parameters: how to guard his powerful employer’s exotic and fragile investments (orchids, ferns, palms) against the harsh Albion weather. For just as Queen Victoria’s empire was finding purchase in the military conquest of distant peoples in distant lands, so squads of imperial plant hunters were combing the hemispheres for new and unusual species.

Recognized as the head gardener for the 6th Duke of Devonshire, he had made his name overseeing the vast estates at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, quick to render the place a notable tourist destination for the surpassing beauty of its grounds. For Paxton, no request, no challenge, from the Duke would go unanswered. Project by project, the necessity of excellence prompted not only the design of sublime landscapes and intricate waterworks but some of the first modern greenhouses. His innovative use of glass and iron in particular, manifested in the invention of a ridge-and-furrow roof, supplied a novel solution to the ongoing question of preservation—neither a new question, nor one for which the existing solutions had advanced much further than those at hand at the time of the Crucifixion, when Tiberian horticulturists contrived sheets of mica to shelter the Roman Empire’s first oranges. In Paxton’s case, the question came down to comparable parameters: how to guard his powerful employer’s exotic and fragile investments (orchids, ferns, palms) against the harsh Albion weather. For just as Queen Victoria’s empire was finding purchase in the military conquest of distant peoples in distant lands, so squads of imperial plant hunters were combing the hemispheres for new and unusual species.

On the morning of his forty-sixth birthday, two years prior to the Great Exhibition, Paxton paid a visit to William Hooker at Kew Gardens. Hooker, who had been serving as the first director of the Royal Botanic Gardens for the better part of the decade, had requested Paxton’s expert assistance for a special assignment. In brief, he had come into the possession of a batch of seeds retrieved from the humid heart of South America. Having successfully propagated these, he intended to pass the torch to Paxton—to see if he could bring about the genuine article: a first flower. This was not just any plant, after all; it was an extremely rare specimen of water lily, known then as the Victoria regia.

Botanists had been describing the plant since the turn of the century. Indeed, other specimens had preceded Hooker’s. But every previous effort to attune the plant to the local climate had ended in failure. As it stood, the challenge was unmistakable: to advance the science, certainly, but also to make one’s name in an unprecedented fashion; to assert that very real right to brag—or to be defeated. For Hooker had offered up seedlings to others, too, not a few of them being Paxton’s (and the Duke’s) rivals. Little surprise, then, in the spirit of public competition, that Victoria regia soon became the talk of the town. And while “Who would do it?” was being bandied about the madding crowd, the question of “Could it be done?” sent shivers down interested spines all across the country. Even Emerson in America could report that Thoreau was staunchly stalking and seeking out the plant’s elusive green form in his Concord ponds.

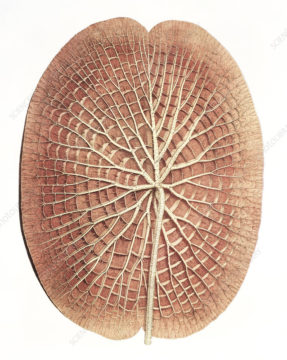

As far as preparations went, Paxton had already read, two years prior, Hooker’s own Description of Victoria Regia, Or, Great Water-Lily of South America. Rendered in a language that strikes the botanically untutored as fantastic, Hooker’s short text speaks of dimensions and proportions that must have seemed fantastic in their own right, if not ludicrous, to most Londoners. The floating leaves (or “lily pads”) were said to grow as large as

six and a half feet in diameter (twelve to nineteen feet in circumference), at first oval with a deep narrow cleft or sinus at one end, in age almost exactly orbicular, peltate, plane but with a considerable depth of margin, which is two to four or five inches broad, and turned up so as to form an elevated rim, like that of a tea-tray; the upper side of this vast leaf is a full green, marked with numerous reticulations which form somewhat quadrangular areolæ; the underside deep purple, sometimes green, according to D’Orbigny, clothed with a short spongy pubescence, furnished with copious very prominent flat veins, radiating from the point of insertion of the petiole and extending to, and through the raised margin, but there becoming less elevated, till they disappear at the very edge; these are united by other deep flattened nerves, and they again by cross ones of less elevation, and all are more or less beset with prickles, varying in length, sharp and horny, subulate, that is, swollen at the base, very much like the sting of a nettle in shape.

six and a half feet in diameter (twelve to nineteen feet in circumference), at first oval with a deep narrow cleft or sinus at one end, in age almost exactly orbicular, peltate, plane but with a considerable depth of margin, which is two to four or five inches broad, and turned up so as to form an elevated rim, like that of a tea-tray; the upper side of this vast leaf is a full green, marked with numerous reticulations which form somewhat quadrangular areolæ; the underside deep purple, sometimes green, according to D’Orbigny, clothed with a short spongy pubescence, furnished with copious very prominent flat veins, radiating from the point of insertion of the petiole and extending to, and through the raised margin, but there becoming less elevated, till they disappear at the very edge; these are united by other deep flattened nerves, and they again by cross ones of less elevation, and all are more or less beset with prickles, varying in length, sharp and horny, subulate, that is, swollen at the base, very much like the sting of a nettle in shape.

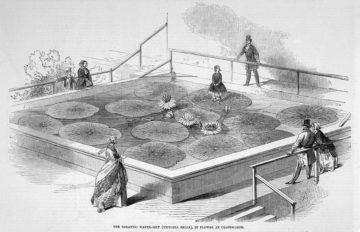

With just such an outcome in mind, Paxton planted his lily at Chatsworth. In the early stages it must have looked tiny, a cowering of green dropped at the center of his most ambitious hothouse yet, where the epic flux of collided worlds (like Taino captives in the Alcazar) remained answerable only to a madness of regulatory oversight: strategically placed ventilation shafts trapped and displaced warm and cool air; heating pipes, buried in the soil, baked the ground; a maximum of glass indulged the plant’s appetite for light; and a system of water-wheels simulated the slight bob and shimmy of an actual jungle pond.

The plant grew steadily. In the second month, a patch of bad weather brought cause for concern, and Paxton thought the lily lost. On the contrary: it grew and grew, and, on the eve of the fourth month, a bud appeared. Paxton was ecstatic. A week later, as Kate Colquhoun writes in her splendid biography of the man,

the bud swelled, rose six inches out of the water, and began to expand. The opening flower was of the purest white, almost a foot across, and it smelled of ripe fruit, something like a pineapple. Over the following evenings as it opened further, its outside petals fell back on to the surface of the water and a pink glow spread out onto the petals from the center. For three evenings it continued to entrance Paxton and his men before, fully tinged pink, it wilted and fell away.

Other buds followed. The second to bloom was carted off to the Queen. (Victoria would eventually knight Paxton—ostensibly for his role in designing the Crystal Palace, but probably, in actuality, for the more personal note with which he presented this rarer fruit of his labor.) Meanwhile, the leaves had multiplied in kind. Just so, they grew broader, stiffer, thicker. Paxton, who had so resolutely answered the question of “Can it be done?”—making his name again, at that—was too busy asking new questions to stop now and brag. His decision to set his young daughter Annie atop one of the largest of the mature leaves may have originated in a spirit of whimsical inquiry. In any event, it would turn out to be one of the most fortuitous moves of his career.

Other buds followed. The second to bloom was carted off to the Queen. (Victoria would eventually knight Paxton—ostensibly for his role in designing the Crystal Palace, but probably, in actuality, for the more personal note with which he presented this rarer fruit of his labor.) Meanwhile, the leaves had multiplied in kind. Just so, they grew broader, stiffer, thicker. Paxton, who had so resolutely answered the question of “Can it be done?”—making his name again, at that—was too busy asking new questions to stop now and brag. His decision to set his young daughter Annie atop one of the largest of the mature leaves may have originated in a spirit of whimsical inquiry. In any event, it would turn out to be one of the most fortuitous moves of his career.

Pilgrims arrived from all around to bare witness to Paxton’s triumph at Chatsworth. Hooker was invited down to make an inspection; the press showed up in droves; and rather than to make nice and hang their heads before so much exotic green grandeur, certain rivals simply pleaded a sore throat. Even if Lewis Carroll failed to make the trek, he would have read about it in the paper—because when little Annie stepped onto that leaf, and its green expanse supported her like a cup in its saucer, a vision of Wonderland gleamed briefly on the water.

Following a few more experiments, Paxton concluded that a single leaf could support not one but all of five small children. Flipping one of the leaves onto its back he gathered, all at once, the significance of Hooker’s original description, noting again those “copious very prominent flat veins”: he saw how they radiated from the center in a vascular web, how the numerous brace-like “cross” pieces stitched the network together, as the picture impressed on his mind a new form of structural integrity.

* * *

Many of the visitors to the Crystal Palace knew the name of Joseph Paxton. But how many could point to the central transept’s barrel vault—that graceful arc of leaping glass, the structure’s defining feature—and say that it had grown from the seed of a water lily? By the time Dostoevsky stuck out his tongue, the Palace had moved to its final resting place in Sydenham: five years after the Empire State Building went up, the Crystal Palace burnt down. By then, Paxton’s architectural advances had already set the stage for the increasingly glass-dominated constructions of the twentieth century. Curiously, the modern skyscraper is unthinkable without Paxton. Even the Burj Khalifa was predicated, most of all and first of all, upon the existence of an English greenhouse.

Many of the visitors to the Crystal Palace knew the name of Joseph Paxton. But how many could point to the central transept’s barrel vault—that graceful arc of leaping glass, the structure’s defining feature—and say that it had grown from the seed of a water lily? By the time Dostoevsky stuck out his tongue, the Palace had moved to its final resting place in Sydenham: five years after the Empire State Building went up, the Crystal Palace burnt down. By then, Paxton’s architectural advances had already set the stage for the increasingly glass-dominated constructions of the twentieth century. Curiously, the modern skyscraper is unthinkable without Paxton. Even the Burj Khalifa was predicated, most of all and first of all, upon the existence of an English greenhouse.