“These are dry,

didn’t you soak

the stems in a vase before

you came here?” Mother said

as I showered blood

red rose petals

on her grave.

“These are dry,

didn’t you soak

the stems in a vase before

you came here?” Mother said

as I showered blood

red rose petals

on her grave.

by Carol A Westbrook

The sun has always been an object of fascination and interest, appearing as it does as a bright, shining sphere crossing the daytime sky. On Monday, April 8, many of us will have had the opportunity to see the sun in all its glory as the moon crosses between it and the earth, briefly revealing its spectacular halo, the solar corona. Although we tend to take the sun for granted, an event like this makes us stop and think of how little we know about this celestial object.

Primitive peoples recognized that the sun was the source of all the earth’s heat and light; it was as important as the air we breathe and the water we drink. The sun was necessary to raise food crops and forage. Who could grow a garden in the shade? The sun marked the days and the seasons with a predictable regularity providing security and structure to their lives. The longest days, the shortest days, and the two equinoxes, had a special significance to their lives as they delineated the seasons, and they celebrated these days with feasting and sacrifice and prayers to their gods; and they raised large and impressively accurate monuments to mark these days. Stonehenge inf England is the best known of these monuments, but there are many others such as the pyramid at Chichen Itza in Mexico which casts a shadow in the shape of a serpent climbing the pyramid at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. It is perhaps this disruption in this regularity and dependability that tend to make solar eclipses such memorable—and perhaps frightening–events. Read more »

by Martin Butler

Recently I read an article which included the idea that nature can have rights, something I have to admit I had not come across before, despite a keen awareness that nature needs protecting. I discovered that this is a well-established point of view – there is a lengthy Wikipedia page on the topic. I found this rather odd – it seemed a misplaced use of the concept of a right. But it made me reflect that in the modern world the possession of rights is one of the few ethical ideals that is taken seriously wherever you happen to be on the political spectrum, so it’s understandable why those who want to protect nature might adopt the language of rights.

From the right to bear arms to transgender rights, rights matter across the board, having an authority that religious commandments, the claims of ‘social justice’, and other varieties of moral prescription seem to lack. The idea that we have rights is an unquestioned certainty, but rights are also often a source of considerable conflict in the modern world. Which rights do we actually possess? Do animals have rights? How can conflicting rights, which are presented as fixed, be reconciled? Do some rights automatically trump other rights? If so, how could a hierarchy of rights be devised? The language of rights, it seems, very quickly leads to dogmatism and impasse. Jeremy Bentham certainly had no time for rights:

Natural rights is simply nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense – nonsense on stilts.[1]

He wrote this in an essay entitled “Anarchical Fallacies; being an examination of the Declaration of Rights issued during the French Revolution”(1796). Interestingly, Bentham’s arguments have something in common with Karl Marx’s and Edmund Burke’s critiques of rights – and these two philosophers are at opposite ends of the political divide. Read more »

by Derek Neal

I was listening to “My Turn Now” from Atlantic Starr’s 1980 album Radiant when my friend complained that “they just say the same thing over and over again.” This is true. The part of the song that elicited this comment was near the end, when the lead singer and the backup vocalists engage in a call and response:

I was listening to “My Turn Now” from Atlantic Starr’s 1980 album Radiant when my friend complained that “they just say the same thing over and over again.” This is true. The part of the song that elicited this comment was near the end, when the lead singer and the backup vocalists engage in a call and response:

(Baby, it’s my turn)

Oh, it is my turn now

It’s my turn now

(It’s my turn now)

(Baby, it’s my turn)

I want the world to know

That love is the love you sow

(It’s my turn now)

This is, of course, what music does. Words are repeated, phrases are repeated, melodies are repeated, and the song gets stuck in our heads and we repeat it to ourselves. Techno music, which is one of my favorite genres, is often criticized as being too repetitive, usually due to its ever-present bass drum; what some listeners fail to realize, however, is that once you hear the bass drum enough you stop hearing it. It acts as a sort of metronome, keeping time while melodies, harmonies, and rhythmic elements give shape to the music. When something is repeated, its meaning changes. I’ll say it again: when something is repeated, its meaning changes. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Random Street Composition While Walking Home, March 2, 2024.

Sughra Raza. Random Street Composition While Walking Home, March 2, 2024.

Digital photograph.

by Mike O’Brien

What a week it has been. I’m not referring to military outrages, legal bombshells or pop-cultural bombshells. Rather, I’m referring to the dozens of intensive (and intensely rewarding!) hours I spent catching up on my preferred corner of academic research: the empirical investigation of animal normativity. Big things are happening in this domain. Big things have been happening there for decades, but the pace has noticeably increased in the last two years, at least judging by the output of the authors I tend to follow.

Some of my readers may know that I am particularly interested in the work of Kristin Andrews, currently at York University in Toronto. I have covered some publications of hers in previous columns, most recently 2022’s “A pluralistic framework for the psychology of norms“, co-written with Evan Westra. Since then, no fewer than nine publications have been added to Andrews’ website, many co-authored with other movers and shakers in the burgeoning animal normativity scene. In addition to illustrating the current state of the field, the historical references in these recent publications (if I can call the 1970s and 1990s “historical” without sending a chill up the spines of my peers and elders) also trace the long trajectory of de-anthropocentrizing projects in cognitive and behavioural sciences. A particularly interesting antecedent is 1990’s “Towards a neurobiological theory of consciousness” by Francis Crick (!) and Christof Koch, which called for a program of research into consciousness that presupposed a neuronal rather than linguistic basis for conscious phenomena. A fortuitous proposal, in retrospect, accompanied by some rather interesting specific hypotheses about the underlying neuronal mechanics. Koch’s confidence in the material tractability of consciousness recently cost him a case of wine (presumably now sitting in David Chalmers’ cellar), although he should not be faulted for the mind-sharpening practice of attaching stakes to one’s bets.

To recap my previous coverage of Andrews’ work: In “A pluralistic framework…“, Andrews and Westra sketched out a conceptual toolkit for a research program that could investigate normativity in non-human animals. The main thrust of this project is to remove heavily concept-laden and human-specific definitions and criteria, and in their stead provide minimal, instrumentally serviceable tools that can be applied to a wide variety of animal behaviours. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

Two of the happy discoveries I’ve made in the last two months or so are Brian Klaas’s and Dan Williams’s Substacks. Klaas is an American political scientist who has made his career in the UK, while Williams is a UK philosopher. Both writers have overlapping interests — chiefly, perhaps, in the role of tribal signaling in the formation of political beliefs.

I generally find myself in agreement with much of what both Klaas and Williams write. For this reason, it was significant for me to read posts by each of them, within days of each other, that I found deeply wrong. Both posts circled around the topic of the impoverishment of public discourse, though each post approached the topic from a distinct perspective.

Klaas’s post, “The Death of Serious Politics,” decries the way in which politics “has become subsumed by scandals, outrage, discussions of rhetoric, culture wars, and, above all, focusing on who’s winning and losing at politics rather than who’s winning or losing at solving problems.”

Klaas rehearses the typical candidates for blame. He claims that “We’re governed by narcissistic political influencers who trade in the currencies of eyeballs and clicks, rather than measuring their acheivements by, say, children lifted out of poverty.” He laments “how many of our collective brain cells have been commandeered after being poisoned by Trump’s hateful venom.” He also targets “the full-blown, profit-seeking news industry embedded within the frenetic pace of American life.” Finally, he blames us — “media consumers with digitally shortened attention spans,” and “dopamine-addled consumers of snippets of information.”

Klaas, then, begins with the observation that our public discourse is impoverished and then provides a diagnosis: our politicians are vapid influencers, Trump has coarsened the discourse, the media is profit-driven and — because of this — focused on driving ratings, and we the media consumers only pay attention to superficial factoids, rather than substance.

As it so happened, a few days before Klaas published his post, Dan Williams published a post discussing the fact that “In politics, the truth is not self-evident. So why do we act as if it is?” Although the topic of Williams’s post might seem orthogonal to Klaas’s, the two are actually quite closely connected. To appreciate this, let’s first see what Williams has to say about what he sees as a “harmful delusion” that many people harbor about their political beliefs. Read more »

by Barry Goldman

Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them… well, I have others. —Groucho Marx

It’s easy to ridicule politicians for their lack of principle. Mitch McConnell comes immediately to mind. When Antonin Scalia died nine months before the 2016 election, President Obama nominated Merrick Garland to replace him on the Supreme Court. McConnell refused even to give Garland a hearing. He said, “The American people may well elect a president who decides to nominate Judge Garland for Senate consideration. The next president may also nominate someone very different. Either way, our view is this: Give the people a voice.”

Four years later when Ruth Bader Ginsberg died 47 days before the 2020 election, President Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett. The voice of the people did not figure in McConnell’s calculations. He fast-tracked Barrett’s nomination, cut off debate, and engineered her confirmation eight days before the election, after millions of Americans had voted.

Predictably, there were loud cries of hypocrisy. Just as predictably, they had no effect. The universe of politicians is not a good place to look for moral principle.

How about the courts? The whole idea of the rule of law is that laws are supposed to be based on principle, applied without fear or favor, and above politics. The reality, of course, is otherwise. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Rebecca Baumgartner

It feels like every week tech journalism brings us a dispatch about the “end” of something: we’re told now that we’re reaching the end of foreign-language education due to advances in AI translation.

It’s true that no field of study is immune from journalistic swagger about our AI-saturated future, but this seems especially true for the arts and humanities, which have been said to be declining for a long time – and which, because their defenders struggle to articulate a compelling ROI, make them appear, to some people, ideal for outsourcing. According to this view, learning French is on a level with monotonously picking orders in a warehouse: If nobody wants to do it, let’s make the AI do it. And it seems that fewer and fewer of us want to learn French – and most other languages, too.

I think the world would be a better place if no human being had to pick orders in a warehouse ever again. By all means, let the robots knock themselves out trying to optimize how quickly we get our Amazon orders. They don’t have a soul to crush. But unlike the rote, mindless work that many humans currently have to do to make a living, creating and enjoying culture isn’t a burden we should rush to relieve ourselves of. Cultural products are not something that can – or should – be optimized in the way that AI models (and the humans behind them) lead us to believe they can.

By the way, it’s important to note that this has nothing to do with whether AI language models can translate a given text “correctly” (however that’s defined for a given text). It’s not even a question of whether the resulting translation is good or not, according to some normative standard of eloquence or naturalness. Read more »

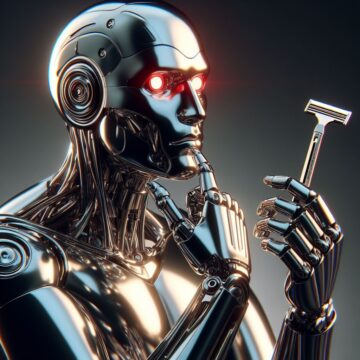

by Jochen Szangolies

Recently, the exponential growth of AI capabilities has been outpaced only by the exponential growth of breathless claims about their coming capabilities, with some arguing that performance on par with humans in every domain (artificial general intelligence or AGI) may only be seven months away, arriving by November of this year. My purpose in this article is to examine the plausibility of this claim, and, provided ‘AGI’ includes the ability to know what you’re talking about, find it wanting. I will do so by examining the work of British philosopher and logician Bertrand Russell—or more accurately, some objections raised against it.

Russell was a master of structure in more ways then one. His writing, the significance of which was recognized with the 1950 Nobel Prize in literature, is often a marvel of clarity and coherence; his magnum opus Principia Mathematica, co-written with his former teacher Alfred North Whitehead, sought to establish a firm foundation for mathematics in logic. But for our purposes, the most significant aspect of his work is his attempt to ground scientific knowledge in knowledge of structure—knowledge of relations between entities, as opposed to direct acquaintance with the entities themselves—and its failure as originally envisioned.

Structure, in everyday parlance, is a bit of an inexact term. A structure can be a building, a mechanism, a construct; it can refer to a particular aspect of something, like the structure of a painting or a piece of music; or it can refer to a set of rules governing a particular behavioral domain, like the structure of monastic life. We are interested in the logical notion of structure, where it refers to a particular collection of relations defined on a set of not further specified entities (its domain).

It is perhaps easiest to approach this notion by means of a couple of examples. Read more »

by Terese Svoboda

The Slavs inspired the word “slave.” Abductions in Eastern Europe began in the ninth century AD conducted by Spanish Muslims, and the area is still plagued by human trafficking (especially children), with a million more victims per year than in the Americas. [1] My surname means freedom in Ukrainian, Russian and Czech. My ancestors flaunted their liberty at a time when many others were being enslaved – or were they once enslaved and took on this patronymic after they escaped slavery, or were they freed? Many Blacks in the US took on the name Freedman or Freeman after the Civil War.[2]

Few know that Blacks were freed twice before the end of the American Revolution. Eighty-seven years prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, in November, 1775, during the year before the Declaration of Independence, Dunmore’s Proclamation ordered the slaves freed in Virginia. Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, was cornered by colonists on a ship in the Norfolk harbor with only 300 soldiers at the time. His proclamation did not stem from any moral or religious objections to slavery. As governor of Virginia, he had withheld his signature from a bill against the slave trade. He simply wanted help – to use Blacks to protect the Loyalists.

Only months before, Dunmore had been quite popular with all Virginians, Loyalists and patriots, as victor of the Battle of Point Pleasant. Marching alongside a thousand of his ragtag backwoodsmen, he routed the area’s Native Americans, opening up a huge area of West Virginia and Ohio for settlement and speculation. Although treaties had been in place for some time, Dunmore ignored them.[3] George Washington, head engineer of the frontier fort construction on the West Virginia/Ohio border, had purchased quite a bit of its acreage, and like the other developers in the area, wanted the Native Americans gone. No freedom for them. Forced to abandon hundreds of acres of corn and semi-permanent homes, the Native Americans were not counted as “brave and free people” that the Virginians declared themselves to be in their many Resolves published in response to Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation a year later. Read more »

by Barbara Fischkin

Moving forward, I plan to use this space to experiment with chapters of a memoir. Please join me on this journey. Another potential title: “Barbara in Free-Range.” I realize this might be stepping on the toes of Lenore Skenazy, the celebrated former New York News columnist, although I don’t think she’d mind. Lenore was also born a Fishkin, albeit without a “c” but close enough. We share a birthday and the same sensibilities about childhood. These days Lenore uses the phrase “free-range,” typically applied to eggs, to fight for the rights of children to explore on their own as opposed to being over-supervised and scheduled.

I feel free-range, myself. I don’t like rules, particularly the unnecessary and ridiculous ones. My friend Dena Bunis, who recently died suddenly and too soon, once got a ticket for jaywalking on a traffic-free bucolic street in Orange County, California. She never got a jaywalking ticket in other far more congested places like New York City and Washington, D.C.

As a kid, I was often free-range, thanks to my parents, old timers blessed with substantial optimism. I have been a free-range adult. I was a relatively well-behaved teen but did not become a schoolteacher as recommended as a good job for a future wife and mother. I wanted a riskier existence as a newspaper reporter. I did not marry the doctor or lawyer envisioned as the perfect husband for me by ancillary relatives and a couple of rabbis. Instead, I married Jim Mulvaney, now my Irish Catholic spouse of almost forty years, because I knew he would lead, join or follow me into adventures.

I left newspapering as my career was blooming to write books, none of which made me a literary icon or even a little famous. I am glad I wrote them. Read more »

by Michael Liss

Our Government is made up of the people. You are the Government. I am only your hired servant. I am the Chief Executive of the greatest nation in the world, the highest honor that can ever come to a man on earth. But I am the servant of the people of the United States. They are not my servants. I can’t order you around, or send you to labor camps, or have your heads cut off if you don’t agree with me politically. We don’t believe in that. —Harry S. Truman, “Whistle-Stop” speech, San Antonio, Texas, September 28, 1948

He was going to lose and lose big. “Dewey Defeats Truman” seemed more a certainty than what later became a meme. Trailing badly in political polls, dismissed by savvy media figures, beset by multiple crises, both foreign and domestic, he was written off by elected officials even in his own party, who feared he would take down the entire ticket. Perhaps the only person who, in the summer of 1948, actually believed Harry Truman could win in November was Harry Truman.

Why he believed this is hard to say, but why his doubters doubted makes perfect sense: Truman was widely seen as a mediocrity, a product of a corrupt local political machine, undereducated (the first President since McKinley not to have a college degree), a former haberdasher, and even a bankrupt. Perhaps above all, Truman was a commoner, and commoners did not become Presidents, at least not in the 20th Century.

It was an accident that Truman was in this situation. He was FDR’s third Vice President in four terms. Roosevelt’s first, John Nance Gardner, served two terms before the two men had a falling out. Gardner’s replacement, Henry Wallace, was brilliant, accomplished, eloquent, and ultimately what can only be described as a flake. Roosevelt, showing that ice-in-the-veins quality of which he was capable, had others deliver the message to Wallace that he wanted a change. FDR had a favorite choice as well: James Byrnes, whom he had appointed to the Supreme Court in 1941, then convinced to return to the Executive Branch to help with the war effort. But Byrnes had some liabilities—he was perceived as anti-labor, and, while Senator, had helped spearhead Southern opposition to a federal anti-lynching law. For these reasons, FDR considered but ultimately rejected Speaker Sam Rayburn (Texas), and finally turned to Truman. Read more »

A moment’s a poet’s take of a singular blur

as tentative as an airborne bubble and

hard as a hammer blow to thumb,

the smallest thing able to contain an unimaginable universe,

a universe able to imagine the smallest thing.

Her’s one now, notice how quick— joy, gone.

Hear’ s another, notice how slow— pain, gone.

A moment’s as swift as that, as if a bullet grazing an ear,

as if a celestial spark in a thunderstorm,

as brief as a flash of thought instantly forgotten in regret

as in love lost and won again, tiny as a lepton

crammed with next . . .

Jim Culleny

7/26/22

I give up.

ONE: An Alien

A.I. is a visitor from another planet, perhaps even from another galaxy, maybe from the beginning of the universe, or the end. Is it friend, or foe? Does it want to see our leader? Perhaps it is interested in our water supply. Maybe it’s concerned about our propensity for war and our development of atomic weaponry. Or perhaps it is just lost, and is looking for a bit of conversation before setting out to find its way back home.

TWO: A Walk in the Park

Or a lark ascending. A cool breeze. A trip to the bank. Godzilla’s breath. Rounding third base. I’ve lost track.

THREE: Code

But really, it’s not that fanciful. It’s just code. Ones and zeros. No more, no less. In itself, nothing. In context, anything at all.

FOUR: A Mirage

An object of desire. An aphrodisiac. But also a soporific, an emetic, a vaccine, a laxative, and stimulant. Neither snake oil, nor homeopathic joy juice, A.I. brings sound to the blind, sight to the deaf, and courage to the faint of heart.

FIVE: Kumquat

None of the above. AIs are Kumquats.

Kumquats (/ˈkʌmkwɒt/ KUM-kwot), or cumquats in Australian English, are a group of small, angiosperm, fruit-bearing trees in the family Rutaceae. Their taxonomy is disputed. They were previously classified as forming the now-historical genus Fortunella or placed within Citrus, sensu lato. Different classifications have alternatively assigned them to anywhere from a single species, Citrus japonica, to numerous species representing each cultivar. Recent genomic analysis defines three pure species, Citrus hindsii, C. margarita and C. crassifolia, with C. × japonica being a hybrid of the last two.

The edible fruit closely resembles the orange (Citrus sinensis) in color, texture, and anatomy, but is much smaller, being approximately the size of a large olive. The kumquat is a fairly cold-hardy citrus. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

A little over a year ago I published an essay here at 3QD that implored my fellow educators not to panic amid the dawning of Artificial Intelligence. Since then I’ve had two and a half semesters to consider what it all means. That first semester, many of my students had not even heard of AI. By the very next semester, a shocking number of them were tempted to have it research and write for them.

A little over a year ago I published an essay here at 3QD that implored my fellow educators not to panic amid the dawning of Artificial Intelligence. Since then I’ve had two and a half semesters to consider what it all means. That first semester, many of my students had not even heard of AI. By the very next semester, a shocking number of them were tempted to have it research and write for them.

Many of my earlier observations about how to avoid AI plagiarism still hold: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure; good policies and clear communication from the jump are vital; assignments such as in-class writing and oral exams are foolproof inoculators.

However, other, more abstract questions with profound pedagogical implications are emerging. These can be put under the larger canopy of: What am I teaching them and why?

Us Historians specifically, and Liberal Artists more generally, help students develop certain skill sets. We train them in the Humanities and Social Sciences, teaching them to find or develop data and use it effectively through critical and creative thinking. Obviously a political scientist and a continental philosopher go about this differently. However, the venn diagram of their techniques and goals probably overlaps a fair bit more than a lay person might realize. For starters, we all have the same broad subject matter. Everyone in the Liberal Arts, from art historians and literature profs to psychologists and economists, studies some aspect of the human condition. And while we each have our own angles of observation and methodologies, there are also substantial similarities among them. We all find or generate data (even if forms of data are different), analyze them, draw conclusions, and present our findings. And those presentations of findings, even when centered around quantitative data, include a narrative.

In other words, words. Read more »

by Jeroen Bouterse

“You are aware”, I ask a pair of students celebrating their fourth successful die roll in a row, “that you are ruining this experiment?” They laugh obligingly. In four pairs, a small group of students is spending a few minutes rolling dice, awarding themselves 12 euros for every 5 or 6 and ‘losing’ 3 euros for every other outcome. I’m trying to set them up for the concept of expected value, first reminding them how to calculate their average winnings over several rounds, and then moving on to show how we calculate the expected average without recourse to experiment. It would be nice, of course, for their experimental average to be recognizably close to this number. Not least since this particular lesson is being observed by the Berlin board of education, and the outcome will determine whether or not I can get a teaching permit as a foreigner.

“You are aware”, I ask a pair of students celebrating their fourth successful die roll in a row, “that you are ruining this experiment?” They laugh obligingly. In four pairs, a small group of students is spending a few minutes rolling dice, awarding themselves 12 euros for every 5 or 6 and ‘losing’ 3 euros for every other outcome. I’m trying to set them up for the concept of expected value, first reminding them how to calculate their average winnings over several rounds, and then moving on to show how we calculate the expected average without recourse to experiment. It would be nice, of course, for their experimental average to be recognizably close to this number. Not least since this particular lesson is being observed by the Berlin board of education, and the outcome will determine whether or not I can get a teaching permit as a foreigner.

In case they are reading this, I would like to emphasize that I plan all my lessons with care and forethought; but for this particular one, you can bet I prepared especially well and left nothing to chance. Except for the part I left to chance, that is. To be precise: I had neglected to calculate in advance how likely it was for the experimental average over roughly 80 games to diverge from the expected value by a potentially confusing amount. I relied on my intuition, which informed me that 80 is a large number.

Turns out it’s not that large after all. The probability of at least 50 cents divergence (which would bring the experimental average at least as close to another integer as to the expected value of 2 euros) is, I have now figured out, a whopping 56%. There was only a 0.6% chance for the experimental average to exceed, as it did, 4 euros, but I had also implicitly accepted a 4% chance that the results would have been closest to 0 or even negative. Just imagine the damage that would have caused.

It would not have been the first time for a probability experiment to result in my pleading with my students to trust the math over actual results they have just seen with their own eyes. The Monty Hall problem has been especially awkward at times. Read more »