by Rafaël Newman

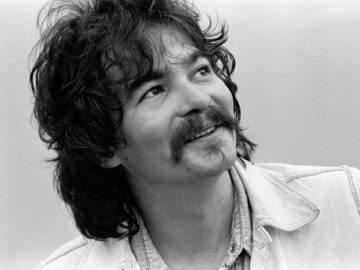

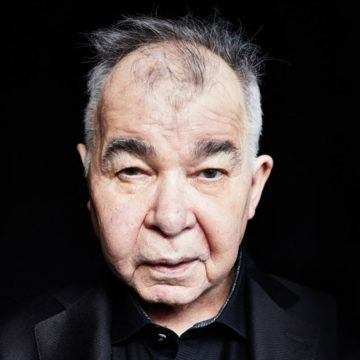

Today I am giving thanks for the life and work of John Prine, the late, great American singer-songwriter, whose date of birth is October 10, 1946, and who died, of COVID-19, on April 7, 2020.

I am listening to his music and thinking about where he came from, and where he wound up: Prine was born in Illinois but his parents were from Kentucky, where he would spend time in his youth visiting family; his career started in Chicago but he ended his days in Nashville, where he co-founded his own independent record label, Oh Boy Records.

I mention these geographical poles in the life of the birthday boy because they help me make sense of my own intimate, visceral response to John Prine’s work. I was introduced to his music in Toronto in the early 1980s by my high-school sweetheart, whose own parents were from Kentucky, having migrated north, to what is effectively Canada’s Midwest, just like Prine’s folks had when they moved to Illinois. (Of course, having done part of his military service in Canada, William Faulkner is said to have noted the similarities between his own native Deep South and America’s ostensibly ur-Yankee neighbor to the north: but that’s another story.)

My girlfriend thus shared with John Prine a similar dual cultural allegiance, to the “South” and to the “North,” manifest in Prine’s music in its blend of a country idiom reminiscent of the Alabamian Hank Williams with a progressive folk sensibility more akin to that of Pete Seeger, a genteel New Englander. Think of the (subdued) war protest in songs like “The Great Compromise,” “Sam Stone,” and “Hello In There,” or the more overt revulsion at American belligerence and patriotic humbug evident in “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore,” written in 1968 but recycled in the 2000s as a fuck-you to George W. Bush’s bloodthirsty jingoism. (Bush Jr also gets a more tailor-made jab in “Some Humans Ain’t Human.”) And no American hawk could accuse Prine of opportunistic pacifism, either: early in his life he served a stint with the U.S. Army in Germany.

But there’s also something else about John Prine that makes (idiosyncratically, in my case) for a further link to a “Northern” culture: like Leonard Cohen, the patron saint of my own hometown of Montreal, whose ballads are lent fresh nuances in a woman’s cadence, Prine attracted the emulation of women, fellow female artists who covered his songs and lent them a new twist. Bonnie Raitt and Bette Midler have performed magnificent versions of Prine numbers, while their younger colleague Carsie Blanton posted a heart-wrenching tribute song she had composed on the occasion of his death, in 2020. Indeed, in at least one song, “Angel from Montgomery,” Prine sings in the female first person: “I am an old woman, named after my mother…” Try to imagine Hank Williams doing that. (The closest a male country singer I can think of has come to this sort of gender non-conformity is Johnny Cash, in “A Boy Named Sue”—but then, Cash was a maverick; and anyway the song turns out to be a covert encomium to toxic masculinity.) Prine even recorded an entire album of duets—In Spite Of Ourselves—with women, mostly ironic takes on cover songs and standards, by the likes of Tex Ritter, Don Everly (of the Everly Brothers), and, yes, Hank Williams, as well as an original John Prine tune, composed for the occasion: the eponymous cut, a paean to settling for the one you’re with that is also a raucous tribute to unorthodox heterosexual relationships.

Here Prine may have been channeling the spirit of another, even more widely revered, more traditionally country singer, who shared his experience between the poles of American culture: Loretta Lynn, who died this past week at the age of 90, and who also hailed from Kentucky but spent some of her formative early married years in the Pacific Northwest. Lynn went on to write at least one anthem of feminist protest, perhaps inspired by the more progressive spirit of Washington State. But Prine’s palette is more versatile still, and certainly more nuanced than any country singer’s, and most folk artists’ as well: his songs range over subjects as disparate, and untypically lyrical, as sex and romance amongst the neuro-diverse (“Donald and Lydia”); cults and hippie communes (“Come back to us Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard”); relations between European settlers and the indigenous peoples of North America (“Lake Marie”); the human cost of fossil-fuel extraction (“Paradise”); and advice columns (“Dear Abby”). There are also innovative re-workings of standard country themes, such as life in the penitentiary system (“Christmas in Prison”), which serves up a heart-wrenching sentimental twist, somewhere between the naïve abandon of Elvis’s “Jailhouse Rock” and the sociopathic melancholy of Johnny Cash’s “Fulsome Prison Blues.” Then there’s “Grandpa Was a Carpenter,” an ostensibly patriotic ode to good ole boys down home that contains a sly twist on Nixon’s notorious “Southern Strategy”:

Grandpa was a carpenter

He built houses stores and banks

Chain smoked camel cigarettes

And hammered nails in planks

He was level on the level

And shaved even every door

And voted for Eisenhower

‘Cause Lincoln won the war.

Prine won the prestigious PEN/Song Lyrics Award in 2016, bestowed by an eminent panel of judges including Paul Simon and Elvis Costello and shared that year with the equally sui generis Tom Waits. He was widely recognized as a national treasure, and received four Grammy Awards, as well as one for Lifetime Achievement. But the single most unmistakable characteristic of Prine’s œuvre is its pervasive humility, its self-deprecating irony, and its utterly plausible lack of braggadocio and vanity. (In one recording, made towards the end of his life, Prine gamely incorporates an absurd mondegreen, or creative mishearing of his lyrics, into the live performance of a celebrated song.) He wrote his own epitaph early in his career, the raunchy, voice-from-beyond “Please Don’t Bury Me” on his third album (Sweet Revenge, 1973); and the text serves to this day as a living will-cum-obituary:

Prine won the prestigious PEN/Song Lyrics Award in 2016, bestowed by an eminent panel of judges including Paul Simon and Elvis Costello and shared that year with the equally sui generis Tom Waits. He was widely recognized as a national treasure, and received four Grammy Awards, as well as one for Lifetime Achievement. But the single most unmistakable characteristic of Prine’s œuvre is its pervasive humility, its self-deprecating irony, and its utterly plausible lack of braggadocio and vanity. (In one recording, made towards the end of his life, Prine gamely incorporates an absurd mondegreen, or creative mishearing of his lyrics, into the live performance of a celebrated song.) He wrote his own epitaph early in his career, the raunchy, voice-from-beyond “Please Don’t Bury Me” on his third album (Sweet Revenge, 1973); and the text serves to this day as a living will-cum-obituary:

Woke up this morning

Put on my slippers

Walked in the kitchen and died

And oh what a feeling!

When my soul went through the ceiling

And on up into heaven I did ride

When I got there they did say

John, it happened this-a way

You slipped upon the floor

And hit your head

And all the angels say

Just before you passed away

These were the very last words

That you saidPlease don’t bury me

Down in the cold cold ground

No, I’d druther have ‘em cut me up

And pass me all around

Throw my brain in a hurricane

And the blind can have my eyes

And the deaf can take both of my ears

If they don’t mind the sizeGive my stomach to Milwaukee

If they run out of beer

Put my socks in a cedar box

Just get ’em out of here

Venus de Milo can have my arms

Look out! I’ve got your nose

Sell my heart to the Junkman

And give my love to RoseGive my feet to the footloose

Careless, fancy free

Give my knees to the needy

Don’t pull that stuff on me

Hand me down my walking cane

It’s a sin to tell a lie

Send my mouth way down south

And kiss my ass goodbye

“Send my mouth way down south”—Prine’s progressive message broadcast to the more conservative milieu with which he is also affiliated. Sounds like a good idea.

As for Rose, she sends her love right back at you, John.