by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

世中は何にたとへん水鳥のはしふる露にやとる月影(無常)

Mujō (Impermanence)

To what shall I liken this world?

But to moonlight

Reflected in the dewdrops

Shaken from a shorebird’s bill

—Dōgen

1.

Eight hundred years ago, a Buddhist monk, not long into his career, became deeply dissatisfied with the Buddhist teachings available to him in Japan. And so, he traveled across the sea to Song China.

A man on a mission, he wanted to uncover the “true Buddhism.”

This is a story repeated again and again as Buddhism made its way East. Monks and priests, feeling like something had to be “lost in translation,” took to the road in search of the true word. From Japan to China and from China to India—and sometimes as far as to Afghanistan, these early translators were seeking to understand the wisdom that was embedded in the words themselves.

Or maybe what they were really seeking was beyond the words themselves?

The monk Dōgen, after seven or so years in China would return to Japan—his mind filled with all that he had seen and all that he had learned. In time, he would form a new school of Buddhism in Japan: Sōtō Zen.

Interested in notions of time and being, he wrote elaborate philosophical tracts, as well as many marvelous poems.

In the above poem on impermanence, Dōgen compares ultimate reality to that of a reflection: of moonlight reflected in a dewdrop scattering off a waterbird’s bill.

In my first translation attempt, I chose to render mizudori 水鳥 (waterbird) as “shore bird.” It is a valid translation for the Japanese term mizudori, which literally means 水 water 鳥 bird. Maybe I instinctively went with shorebird because I have been taught in creative writing classes to try and be as concrete and specific as possible, so readers can better form mental images. Could this might explain why the translation I found online (made by the great Dōgen-scholar Steven Heine) used the English word “crane” for mizudori.

Dōgen did not choose the Japanese word for crane, which is tsuru 鶴 so why did the translator?

Curious, I looked at another poem by Dōgen that makes use of the same word mizudori 水鳥 (waterbird):

水鳥の行くも帰るも跡たえて され共路はわすれさりけり

水鳥の行くも帰るも跡たえて され共路はわすれさりけり

Waterbirds depart and return

Without ever leaving a trace

Yet they never forget

The path they have taken

In reading this poem, it hit me that “migratory bird” is really what is being evoked in the first poem—And yet, that is not what the Japanese says. Migratory bird has its own word: wataridori 渡鳥.And that is not used in either poem.

2.

A question:

When you imagine the disappearing “tracks” of birds flying south in mid-autumn, do you picture cranes or geese? Or maybe some other bird? Speaking for myself, I imagine geese. In Los Angeles, I almost fell off a bar stool once as I tracked a row of geese flying south across the sky, hoping they would land at the lake near my mom’s house.

In Madison, where I went to grad school, their calls were a beautiful constant on autumn nights. I loved watching them soaring in great V-shapes across cloudless skies.

For more than a thousand years, migratory birds have served as a trope for the enlightened mind in the Buddhist poetic world –because these traveling birds evoke another expression: “Activating the mind without dwelling”

詠応無所住而生其心

This is from the Kumarajiva’s Chinese translation of the Diamond Sutra, which teaches that we should aim for an uncluttered mind, free of attachments.

To walk the path without leaving a trace

To not “dwell” on the things of the world

When I was a university student, I fell in love with an older man whom I found to be a bit of a puzzle. He was not a Buddhist but a Sikh, and he often told me about his hope to live without leaving a trace. No dwellings. Literally, he did not have a mortgage, donating most of his salary to his temple and to other causes and he was very firm about not getting ensnared in the “things” of the world. Because he used the phrase, “not leaving a trace,” I thought of him immediately reading the second poem.

3.

In the first translation, even before I started worrying about how to handle the English for “waterbird,” I felt bothered about the use of “dewdrop” instead of water drop. Waterbirds are in water so shouldn’t it be water droplets?

Thinking about geese, you do actually find them in dewy fields. Could that be why the translator chose to translate mizudori as “crane?” My own favorite waterbird is a goose. The Hawaii goose, called the nene, is often found in dewy grass. Descended from Canada Geese, the nene gets its name for its soft call that is reminiscent of crickets chirping. I once got a bit too close to some ducklings on the slopes Mauna Kea, and before I knew it, the father goose bent low and charged me!

Thinking about geese, you do actually find them in dewy fields. Could that be why the translator chose to translate mizudori as “crane?” My own favorite waterbird is a goose. The Hawaii goose, called the nene, is often found in dewy grass. Descended from Canada Geese, the nene gets its name for its soft call that is reminiscent of crickets chirping. I once got a bit too close to some ducklings on the slopes Mauna Kea, and before I knew it, the father goose bent low and charged me!

I love geese. And so, I wonder why Dōgen didn’t choose geese for his poem, in the way you find in Chinese poems about enlightenment.

Even even if I never so come to understand Dōgen’s chose of waterbird, at least I get why it had to be dewdrops 露—and not water droplets. I have written at length —in these pages— about how the dewdrops in autumn are a code for impermanence in Buddhist thought.

The Diamond Sutra teaches that, All that appears before us is as a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow. All is like the dew or lightening. Everything is in flux and that all must eventually perish is a sad but inevitable fact that somehow seems all the more apparent in this season of sparse autumn grass, disappearing dewdrops and sudden, passing thunderstorms.

It is not surprising that Dōgen would be interested in notions of impermanence given his life trajectory. Born into one of the great literary and aristocratic families of the time, he lost both his parents at a very young age: first his father and then his mother. And yet, rather than commenting on the way flux and change governs our lives, what was being said was much more radical. For Dōgen, impermanence did not mean something like: “all good things come to an end.” Mujō is a statement about time itself. Our understanding of past, present and future is illusory, says Dōgen. Things don’t exist the way we think they do. And for Dōgen, time is the key to understanding this.

4.

4.

An ancient Greek once commented that the reason poetry translation is so hard is that you are not rendering the words of one language into those of another but rather are trying to translate one poem into another poem. In this case, we are working from heavily compressed Japanese, where one word can convey so many layers of meaning and allusions. It is challenging; for there is a puzzle-quality about getting it right. Trying to retain as much as possible from the original whilst still getting it to “work” in English.

So often, the words keep unravelling, posing ever new obstacles.

Above, I mentioned how the word for migratory birds is connected to that of dwelling. To dwell on something is a kind of Buddhist “hindrance.” It is to leave tracks. Like ruts in our brain, so to speak. It reminds me of 12th century monk, Kamo-no-Chomei’s Hōjōki. The opening lines are very famous and are something many Japanese people can recite by heart:

The river flows ceaselessly without stopping. And yet, the water is never the same. Bubbles appear and disappear on stagnant pools—never lingering long. And so too it is with people…

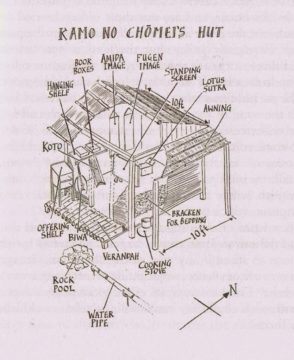

Hōjōki gets its name from hōjō 方丈, which is an architectural term representing one square jō 丈—about ten-foot square. This then, conveys a small, cell-like space, is also used for a monk’s living quarters, especially in the Zen tradition. The hut is tiny, but somehow there is a living area, along the eastern wall in the form of his “dried bracken for a bed”. This bed is but a hand’s reach away from his musical instruments—his lute and koto—sitting beside a shelf holding his music and poetry, and a few books.

In Medieval Buddhist literary terminology, houses are code for the mind. Dwelling in a house reflects how the mind “dwells” in the things of the world. In this way, Chōmei—born to privilege and talent—gives it all up to become a Buddhist recluse in the Hills of Hino. And there, in his ten-foot square hut, he realizes that everything in the world comes down to the state of one’s mind. As he says,

Reality depends upon your mind alone. If your mind is not at peace, what use are riches? The grandest halls will never satisfy.

5.

5.

If the tracts of migrating birds or the grand houses of people signify the “small self” for Dōgen, perhaps more than any other image, it is the moon that suggests enlightenment.

「人の悟りをうる、水につきのやどるがごとし。月ぬれず、水やぶれず。ひろくおほきなる光にてあれど、尺寸の水にやどる。全月も弥天も、草の露にもやどり、一滴の水にもやどる。」

Enlightenment is like the moon reflected in the water. The moon does not become wet, nor does the water become disturbed. The light is so vast and yet it is reflected even in a drop of water. The entirety of the moon and all of heaven (the sky?) can be glimpsed in a dewdrop on a blade of grass.

For me, what is interesting is the metaphor of reflection. This is neither transcendence nor immanence. As reflected Light, the image evokes the “world in a grain of sand idea,” which is short-hand for that of an inter-dependent, co-arising reality. A radical denial of duration. (As Spinoza said, eternity cannot be explained by duration).

The short poem unlocks a multitude of ideas and images, philosophies, and understandings of being. It is what is so endlessly interesting about literary translation.

When I was young, I used to grow a bit envious when I’d hear people talking about the translation practice they had to do in high school. Usually these were in the form of complaints about the mind-numbing nature of translating obscure passages from Latin or Greek into English. Such complaints are mostly coming from older people, often speaking of their experiences in the UK.

But did you know there was once a US president who could write passages in ancient Greek with his right hand as he simultaneously translated them into Latin with the left?

In the U.S., we talk about introducing language studies into the public schools for kids at an earlier age, with a strong emphasis on verbal communication. I think this misses the deep value of learning from a literary tradition. Being able to order food or have a basic conversation in another language is also a wonderful thing, of course. After years of studying French, I was never able to communicate anything! Years later, I studied Bahasa Indonesia for a short time in Bali. And I will never forget the first time I spoke a few words –and presto! A cup of coffee appeared. No one would ever diminish the fun and importance of verbal human-to-human communication.

I do think, however, that literary translation can unlock other chambers in one’s mind. Not only does thinking in a different language allow for a critical distance from one’s own preconceived notions but the very act of translating can become a key for seeing the world in new ways –and it is something people can do in the solitude of their own minds without ever leaving their room.

++

For part one of my series on translators, see my essay, The Heart Of The Matter: Translating The Heart Sutra.

More things Japanese on my Substack: Dreaming in Japanese (Please subscribe!)

Birding with legend Jack Jeffrey in the Hakalau Preserve (Video).

Recommended reading: Impermanence Is Buddha-Nature: Dо̄gen’s Understanding of Temporality by Joan Stambaugh