by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

A new study has revealed a troubling development in the state of Maryland: while murder rates fluctuated between 2005 and 2017—first trending downward, then increasing for a few years—the homicides recorded during that period have grown steadily more violent the entire time.

A new study has revealed a troubling development in the state of Maryland: while murder rates fluctuated between 2005 and 2017—first trending downward, then increasing for a few years—the homicides recorded during that period have grown steadily more violent the entire time.

According to “Increasing Injury Intensity among 6,500 Violent Deaths in the State of Maryland,” which is forthcoming in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, researchers examined the intensity of deadly incidents over a 13-year period. Intensity was measured by the number of gunshots, stab wounds, and fractures exhibited by victims. Across all three causes of death, while the rate of homicides varied during the period, the percentage of high-violence crimes consistently increased.

Conducting the study was easier in Maryland than it might have been in other states. Maryland is unusual in that its Chief Medical Examiner is required to report on all murders, suicides, and unusual deaths, which means that researchers had access to a broad-based data set. State policy meant that researchers had access to information about victims who died under medical care and those who died at the scene of the crime. The state’s data set was geographically comprehensive, too, including cases from Baltimore’s urban center, the suburban areas around Baltimore and Washington, DC, and the rural areas in the eastern and western parts of the state. Read more »

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory. All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

Is there such a thing as tasting expertise that, if mastered, would help us enjoy a dish or a meal? It isn’t obvious such expertise has been identified.

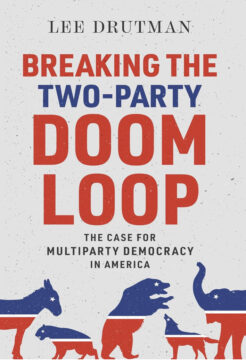

Is there such a thing as tasting expertise that, if mastered, would help us enjoy a dish or a meal? It isn’t obvious such expertise has been identified. It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2)

It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2) I’m writing this 37,000 feet above Vestmannaeyjar, a chain of islands off Iceland’s south coast. Or so the screen tells me – I can’t see the view because I’m wedged into 38E, a middle seat at the back near the loos.

I’m writing this 37,000 feet above Vestmannaeyjar, a chain of islands off Iceland’s south coast. Or so the screen tells me – I can’t see the view because I’m wedged into 38E, a middle seat at the back near the loos.

Kathleen Ryan. Bad Lemon (Creep), 2019.

Kathleen Ryan. Bad Lemon (Creep), 2019.

In an attempt to understand my relationship to the Italian-American identity, I recently began watching episodes of The Sopranos, which I avoided when it first aired twenty-five years ago. I was on a nine-month stay in New York at the time, living in a loft on the Brooklyn waterfront, and I remember the ads in the subways—the actors’ grim demeanors; the letter r in the name “Sopranos” drawn as a downwards-pointing gun. I’ve always been bored by the mobster clichés, by the romanticization of organized crime: as an entertainment genre, it’s relentlessly repetitive, relies on a repertoire of predictable tropes, and it has cemented the image of Italian Americans we all, to one degree or another, carry around with us. But the charisma of Tony Soprano, played by James Gandolfini, exerts an irresistible pull: I jettison my critical abilities and find myself binge-watching several seasons, regressing for weeks at a time, losing touch with what I was hoping to find.

In an attempt to understand my relationship to the Italian-American identity, I recently began watching episodes of The Sopranos, which I avoided when it first aired twenty-five years ago. I was on a nine-month stay in New York at the time, living in a loft on the Brooklyn waterfront, and I remember the ads in the subways—the actors’ grim demeanors; the letter r in the name “Sopranos” drawn as a downwards-pointing gun. I’ve always been bored by the mobster clichés, by the romanticization of organized crime: as an entertainment genre, it’s relentlessly repetitive, relies on a repertoire of predictable tropes, and it has cemented the image of Italian Americans we all, to one degree or another, carry around with us. But the charisma of Tony Soprano, played by James Gandolfini, exerts an irresistible pull: I jettison my critical abilities and find myself binge-watching several seasons, regressing for weeks at a time, losing touch with what I was hoping to find.

I was listening to “

I was listening to “