by David J. Lobina

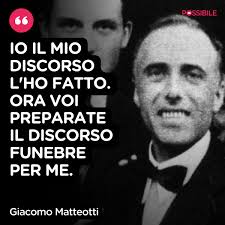

So, then, is the American politician Ron DeSantis a fascist? Is former (and maybe next) US President Donald Trump a fascist? What about the Republican Party these two politicians belong to, is it a fascist party? Are some strands within the modern British Conservative party, to move to this side of the world, a case of fascism too? And is fascism also present, to now move out of the English-speaking world, in the current governments of Italy, Hungary, and Russia or the various opposition parties in France and Spain?

These are some of the questions I have alluded to here and there since my post on the use and abuse of the term fascism in current political commentary, the first of a series of on Nationalism and Fascism. It might be a bit Procrustean to claim that all these currents (and undercurrents) encompass fascism, but this is exactly what one finds in the media, especially in the English-speaking world. In fact, there have been further cases of this sort of talk since my opening salvo, including from the very people I had singled out at the time, whilst the reaction the post received, both publicly and privately, was quite interesting in itself – trebles all around for doubling down!

So, to recap post number 1. The word “fascism” comes from the Italian fascismo, and the political phenomenon is also Italian in origin, properly starting in the 1920s. Both the word and the politics were soon adopted in other parts of Europe, and eventually elsewhere in the world, under different conditions and often becoming, naturally enough, slightly different phenomena. Thus, whilst it is customary, and correct, to consider Mussolini’s and Hitler’s regimes as fascist under a certain reading, Fascism and Nazism (in capital letters) were different in rather important respects, and plenty of scholars treat them as distinct ideological and political movements. Renzo De Felice, for instance, an early and quite influential expert in fascism, did not regard Nazism as a species of Fascism at all, and he argued this was even more the case for Franco’s regime in Spain or Salazar’s in Portugal.[i] Read more »

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau prophetically declared that “we badly need someone to teach us the art of learning with difficulty.” Two hundred and fifty years later, Rousseau’s words seem clairvoyant in their relevancy to schooling in the United States. Education has come to the forefront of the array of issues emerging in the post-Covid era. The abandonment of the alphabet soup of standardized tests, student reliance on Chat GPT, and rampant grade inflation all point to a wider problem. And though some politicians see the Ten Commandments as the solution to classroom troubles, universal progress toward a real solution seems far away. Not that some don’t try.

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau prophetically declared that “we badly need someone to teach us the art of learning with difficulty.” Two hundred and fifty years later, Rousseau’s words seem clairvoyant in their relevancy to schooling in the United States. Education has come to the forefront of the array of issues emerging in the post-Covid era. The abandonment of the alphabet soup of standardized tests, student reliance on Chat GPT, and rampant grade inflation all point to a wider problem. And though some politicians see the Ten Commandments as the solution to classroom troubles, universal progress toward a real solution seems far away. Not that some don’t try.

Sanford Biggers. Transition, 2018.

Sanford Biggers. Transition, 2018. Have you ever read a book that you thought you were going to write? A book that captures something you’ve experienced and wanted to put into words, only to realize that someone else has already done it? The Apartment by Greg Baxter is that book for me.

Have you ever read a book that you thought you were going to write? A book that captures something you’ve experienced and wanted to put into words, only to realize that someone else has already done it? The Apartment by Greg Baxter is that book for me.

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.