by Jochen Szangolies

Humans, Plato famously held, are featherless bipeds: uniquely singled out from other animals by walking permanently on two legs, which delineates us against fish, mammals, and reptiles, while not sporting the sort of plumage associated with birds. Of course, he knew little of the mighty T. Rex (although its featherlessness is subject to recent academic dispute), and Diogenes the Cynic quickly came up with a deflationary argument: he crashed Plato’s school, brandishing a plucked chicken.

Plato was engaged in a project that goes on to this very day: the definition of what, exactly, is it that makes humans human—how we are distinguished from all else that creeps and crawls on the face of the Earth (and presumably, beyond). However, as performatively illustrated by Diogenes, such an endeavor is intrinsically fraught: defining the human is not just a matter of practicality, but what—or who—counts as human impinges on questions of moral standing, of whether to extend certain rights and protections. A standard human, if such a thing existed, would be a norm against which all are compared, and either permitted to enter ‘club human’ or not.

Even this is a simplification, however. The line, here, is not as clear as ‘human’ and ‘not human’—frequently, in the history of humanity, we encounter various categories of ‘human, but’: people that count as human, but not as the special sort of human, the ‘standard human’ that forms the measure of what it means to be truly worthy of all the rights and protections that society affords its most highly valued members.

This too is exemplified in the story of Plato’s featherless biped: what he was trying to define was man, not human. While we might count this as a quirk of a bygone time, or of the ancient Greek language, this attitude is pervasive throughout history, and finds its echo both in overt ostracism of ‘nonstandard humans’ and in subtle slanting of the playing field against those that don’t quite measure up.

An eye-opening illustration of this is what’s known as the Smurfette principle, first brought to my attention thanks to German comedian and feminist Carolin Kebekus, but originally described by the American poet and essayist Katha Pollitt in a 1991 New York Times article. Smurfette is, of course, the only female Smurf in Smurfville. The in-universe explanation of this is that all Smurfs are naturally male, with Smurfette being a failed experiment of the evil wizard Gargamel. I’ll just let that stand for the moment, because the really interesting part is that being female is her main distinguishing characteristic: all of the other Smurfs are given a particular property, talent, or character trait to set them apart—the accident-prone Clumsy Smurf, strong Hefty, skillful Handy, prankster Jokey, and my favorite, Passive-Aggressive Smurf. But for Smurfette, it’s only her being female that distinguishes her from ‘base Smurf’; thus, femininity is one of the possible attributes that may be added to the standard Smurf, but is not part of that standard. With this construal, we have a powerful instrument of singling out whatever we consider nonstandard, and reneging on the rights and protections otherwise bestowed on members of society—just as, for example, we might renege on Bank-Robber Smurf’s right to freedom.

This has, of course, been applied throughout human history. Colonial powers thought the people of the lands they were ‘colonizing’ frequently sub-human; the right to vote, even in contemporary democracies, were often only extended to women after a long history of struggle; full citizenship in Plato’s Athens was only available to adult Athenian males who had completed military training. In each of these cases, and the many besides, the powerful used a construct of what it meant to be truly human to act as a gatekeeping device, and exploit those not awarded membership for their life and labor.

We thus have reason to look at claims of singling out some human standard to compare people against before admitting them into club human with a critical eye. And to be sure, great strides have been made on that front: membership rules have, on the whole, become more permissible, greatly expanding the roster—often to the chagrin of established members, with warnings of grave consequences, and only after a considerable amount of pressure had been exerted on the figurative doors. But moving a boundary is not eliminating it, and while we might congratulate ourselves on our increasing inclusiveness, those left outside suffer no less of an indignity for being fewer. Should we perhaps just give up on the endeavor of trying to legislate what makes a proper human?

Taking Flight

Suppose that, one evening on the news, you hear about a strange occurrence. In various parts of the world, without any apparent relation, a fraction of newborns enter this world with a set of wings on their backs. As these grow up, it becomes apparent that these wings even develop a functionality: we are witnessing the emergence of a group of humans with the ability to fly. What does this mean for you, and for us, who are not so gifted?

Well, beyond perhaps a certain amount of envy, it need not mean anything much at all. Indeed, if such events are sufficiently rare, then you might never encounter these flying humans at all, and learn of them only via modern mass media. Certainly, their existence has no bearing on how you live your life, on the way you accomplish your everyday tasks, or even on your pastimes and recreations. There’s nothing about the mere existence of flying humans that lessens you and your existence in any way.

But now suppose that the capability of flight were dominant in humans, and you are born without wings. The winged humans around you might look at you with pity, might consider you as suffering from a grave birth defect; indeed, some might go so far as to consider your life hardly worth living. And sure enough, in this world, you would likely experience a greater amount of strife than your winged brethren: a world adapted to beings routinely capable of flight is bound to differ greatly from one made for earthbound creatures. Stairs might be a rarity, if they exist at all; buildings might not typically be accessible from the ground level, but rather, via landing-pads high up; safety features against the spontaneous assertion of gravity (i.e. falling) might be absent, leading you to be in much greater danger in everyday situations than others.

Either adapting you to the world—say, by strapping a jetpack to your back, or giving you a set of artificial wings—or adapting the world to you—installing stairs, ground-floor access, guardrails and whatnot—will be an arduous and costly undertaking. You are now effectively disabled: some of the capabilities available to the standard human now elude you. But, as compared to the previous situation, nothing about you has changed; what has changed, rather, is the way the world fits you. In the first story, you inhabited a world geared towards a standard of non-flying humans; in the second, the human world is one of flying beings, of which you aren’t one.

In other words, whether anybody fits the world is at least as much a question of the world and who it caters to—who counts as standard human—as it is of the specific individual—and maybe more so. This has obvious implications for the concept of disability, both physically and mentally: in many cased, the ‘disabled’ are only so before the background of a world maladapted to their needs. Us standard humans might be just as disadvantaged in a world where most are able to sense electromagnetic fields as the deaf or blind are in this one. I suffer from a congenital lack of olfaction—I’m not able to smell, and never have been. It is only the fact that our world, and my navigation of it, does not greatly depend on this ability that makes this a hardly noticeable disadvantage (and in some situations, say a subway on a hot and humid day, it may even be enviable).

But this issue extends beyond (overt) physical or mental disability. Consider the homeless person you pass on your shopping trip: we are, all too often, quick to judge them failures, as having failed to keep up with the demands of modern society due to an inherent weakness of character, or maybe trauma or mental illness. However, we might just as well judge society for having failed to provide them with what they need to thrive. If there is a possible world that allows their flourishing, then there is at least a partial failure on our part for failing to make this world real.

Hence, the standard human is a social construct, and all too often used as a legitimization for choosing the easy way out, by branding whatever falls outside its purview defective, disabled, or undesirable. Giving up on this concept then at least holds the promise of adapting our world to the needs of all, rather than just some arbitrary ‘proper’ notion of what it means to be human.

But are we not being a little too quick here? Certainly, it would not make sense to expand the category of the human beyond certain boundaries. It simply does not make sense, for example, to extend all the rights and protections enjoyed by humans to, say, all mammals. For instance, humans might enjoy a right to freely choose their occupation; extending that right to chimpanzees simply is nonsensical. More carefully, I expect to enter into mutual contracts with humans, to the extent that, if I and another human were to wash up on a desert island, I could still expect them to uphold my right to life, just as I would. I might be wrong in that expectation, but if the other were to kill me, this would entail a breach of contract. If I were in the same situation with a lion, such a contract would make no sense, and I might not consider myself bound to uphold the lion’s right to life in the same way. So are there not certain biological barriers that need to be upheld?

Error And Evolution

The discourse around what should be considered ‘standard’ human is an unfortunate breeding ground for a certain confusion between facts and values. It is this, in my opinion, that underlies often unconstructive accusations of ‘cancel culture’ and the like: a stance is presented on a factual dimension, but evaluated along a moral one, which goes along with an accusation that the one presenting it not merely happens to be wrong, but morally wicked. It is this ellision of the distinction between the ethical and the merely factual regarding the normative claims of human capabilities that is to be resisted, not necessarily those claims in themselves. However, in practice, it is often difficult to keep mind of this separation.

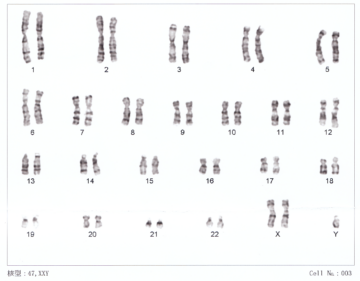

Consider the statement ‘according to biology, there are two sexes’. This is, as it stands, a purely factual claim that may either be true or false, and does not in itself carry any moral connotation. It may be opposed on the basis of biological science, but not on the basis of moral righteousness; one is not inherently wicked for making this claim. It is only once this claim is amplified by a sort of ethical bridge law—such as ‘and any deviation from this is not deserving of the same rights and protections as the standard human’—that a morally abhorrent position emerges. Unfortunately, these bridge laws are often left implicit, and may inform our opinion in the form of unconscious biases, or assumed by those not sharing it as being a malicious ‘true motivation’ behind the stance we take.

There are two directions of (misleading) implication here, that create (largely) unnecessary discord: fact-to-value and value-to-fact. One alleges that biological facts create normative boundaries; that the details of biology allow us to delineate what defines the human, which characteristics are ‘properly human’, and consequently, what instead ought to be considered outside of the norm, or defective. The opposite direction starts from moral values and aims to legislate biological facts, or at the very least, beliefs about these facts: you shouldn’t believe in the narrative of two biological sexes because it causes moral offense to those not falling onto either side of the divide. Consequently, everybody who does hold such a belief can do so only out of moral turpitude.

I think on both sides, a central mistake is failing to allow room for error, or at least, variance. Somebody holding the belief that there are only two proper biological sexes, if this belief is false, may hold it only because of an honest error, and may not in fact buy into the ethical bridge law that turns this into a moral judgment. They are, then, maybe in need of education, but not of moral condemnation.

On the other hand, the belief in this dichotomy is itself insufficiently mindful of the room for variation that is central to biology. Alan Sokal, a physicist famous for submitting a hoax paper to the cultural studies journal Social Text in order to expose what he saw as insufficient standards of academic rigor, has recently defended the ‘biology allows for two sexes’-narrative against the ‘woke invasion’ of the sciences. As he puts it:

[S]ex in all animals is defined by gamete size; sex in all mammals is determined by sex chromosomes; and there are two and only two sexes: male and female.

In the following paragraphs, he admits to ‘quirks of mutation’ that allow for some vanishingly small percentage of individuals to fall outside of this dichotomy, but still, it is, he claims, ‘as binary as any distinction you can find in biology’. (Although some sources estimate a prevalence of up to 1%, which would yield around 80 million individuals—roughly the population of Germany. Not an overly large group, perhaps, but also a bit more than a rounding error.)

Now, as a physicist, I don’t feel qualified to expound on the biological facts. But again, it is not really the existence of this dichotomy that is problematic, but rather, its use as defining what makes a ‘standard human’, and the ostracizement of any that don’t fit it from the club—and thereby, making a world that is ill fit for them. It’s the naturalistic fallacy, the seamless sliding from ‘is’ to ‘ought’, making a biological—ultimately contingent—fact into a normative precept, a way for the proper human to be. A proper criticism attacks this normative aspect, not, as Sokal seems to bemoan, its factual content.

Moreover, biology itself seems an ill fit with the notion of how any particular creature ought to be. A famous dictum in biology, coined by evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky in the eponymous essay, is that ‘nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution’. If that is the case—and I very much believe so—then hard-and-fast boundaries in biology are invariably suspect. The driver of evolution is variation—incessantly tweaking extant designs to see what might fit better. And this variation is arrived at via just those ‘quirks of mutation’ Sokal wants to sideline. Biology always must leave room for error—or better, for variety; in the face of hard-and-fast boundaries, evolution finds no purchase. Being an in-between case is just biological business as usual. The history of life is the exploration of an evolutionary continuum on which every biological entity exists, not the jumping between distinct absolute forms. (Indeed, I find already the notion of life-form itself suspect.) There can be no biological basis for a standard human if what it is to be human is embedded in its proper biological context of continuous variation.

Attempts to legislate on the notion of the ‘standard human’ lead, consciously or not, to a world ill befitting those judged deviant. Moreover, no such notion can be forthcoming from biology alone: not only is variance intrinsic to any biological notion, the very act of appealing to biological characteristics as yielding normative boundaries is logically erroneous. Contrariwise, those sensitive to the injustices perpetuated in the name of the notion of humans proper should distinguish between claims of biological fact, erroneous or not, and norms fallaciously derived from these.

We must always admit room for error: it is there that opposing views may meet.