by Michael Liss

Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

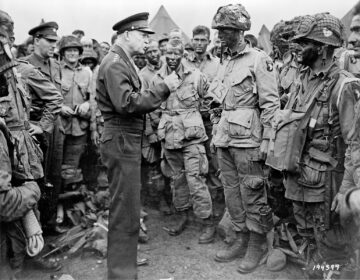

—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, June 6, 1944

We had to storm the beaches at Normandy. There was no other way. None, at least, to loosen Hitler’s death-grip on Western Europe. One by one, proud peoples saw their countries’ armies overwhelmed by Blitzkrieg conducted with a speed and agility that astonished.

First Poland, with Germany’s partner of convenience, the Russians, which then rampaged through Eastern Europe, gobbling up prizes. Then, after a pause for the so-called “Phony War,” the Germans moved on to Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg. May 13, 1940, they pivoted, sent their troops over the River Meuse, blasted and danced past the supposedly impenetrable Maginot Line, and induced the mass evacuation at Dunkirk. The French Army, it could be said the French country, was in full physical and moral retreat. By June 22, it was over. The French were forced into a humiliating armistice in the very railcar in which Germany had accepted defeat in World War I. Hitler literally danced a jig.

Germany occupied roughly three-fifths of European French territory, including the entire coastline across from the English Channel and the Atlantic. Britain had survived the desperate Battle of Britain but stood alone. The Italians joined the Axis to grab some of the spoils for themselves, and, in early 1941, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania followed. In April of that year, the Germans crushed Greece and Yugoslavia.

“Fortress Europe,” essentially a massive buffer zone for the Germans, ending in a fortified Atlantic coastline, became a reality. The Nazis built the Atlantic Wall, a 2,400-mile line of obstacles, including 6.5 million mines, thousands of concrete bunkers and pillboxes bristling with artillery, and countless tank traps. Where there wasn’t a wall, there were cliffs looking over the beaches where Allied forces were expected to land, and, from those cliffs, German soldiers were prepared to rain down fire.

In a sense, this moment had been inevitable for some time. The Germans had to hold in the West because they were squeezed in the East. In June of 1941, driven by frustration over his inability to conquer Britain and his thirst for Lebensraum, Hitler had ordered Operation Barbarossa, a full-scale attack against his Russian allies. Early astonishing successes “melted” in the Russian winter, to be replaced by desperate fight against Russian doggedness.

Where was the United States in all this? Deeply unprepared, not only for what would happen on December 7, 1941, but for war in general, and particularly a two-front war. When, in mid-1940, the Germans were bearing down on Paris, the entire U.S. Army consisted of about 190,000 men—fewer than the armies of Sweden and neutral Switzerland. The appetite for military adventures was minimal, and there was a potent Isolationist wing in the GOP which insisted on keeping it that way.

FDR thought differently, but, as in many things that were ultra-controversial, he moved deliberately, and sometimes with a bit of stealth. It took until September 1940, a year after Hitler had invaded Poland and after the fall of France, for Congress to pass and FDR to sign the first peacetime Draft—the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940—which required men between the ages of 21 and 35 to register with local draft boards.

We were, in short, unprepared, and not merely in how many servicemen we had, but in our manufacturing the implements of war, and perhaps even in our psychology. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, Eisenhower, and even Omar Bradley, called the “G.I. General” for his common touch, all thought the individuality of the American soldier, unaccustomed to rules and perhaps inclined to speak his mind, made for more difficult training, but more creativity in the field. The soldier should understand the essentialness of his job and importance to the nation. He should not be a mere faceless cog. The British did not always agree, and grew impatient with some early American failures, notably an early engagement at Kasserine Pass in Tunisia.

Could America do it? Could it ramp up from what was clearly a cold start, engage successfully with the skilled and ruthless Japanese, who ran the table in early fighting, produce the massive amounts of arms and equipment needed to wage war successfully, and still have the resources to help Western Europe off its back? Would the American public support U.S. involvement in Europe, when the Japanese seemed to be “our war”?

We would have to try. It started, as it had to, with planning. On March 12, 1943, the combined Allied Chiefs of Staff appointed Britain’s Lt. General Frederick Morgan as chief planner for the future invasion, giving him the title “Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander” (COSSAC, for lovers of army acronyms). There arose a core disagreement between the Americans and the British—the Americans wanted to plunge ahead and attack sooner; Churchill and the British service chiefs preferred to start with a Mediterranean-centered strategy, to probe the “soft underbelly of the Axis.” The Americans agreed, but only on the condition of an invasion of northwest Europe in 1944.

Morgan was dealt a difficult hand. Strategically, he had to navigate two separate issues: first, making a land assault on the beaches work, and then, having created a bridgehead, bringing in a sufficiently large and properly supplied force that it could chase and defeat the German Army in the West. What he didn’t know was almost everything—the extent of the resources the Allies could commit a year from then, how well the Russians would be doing on Germany’s Eastern Front, and what German defensive structures and alignments would look like.

One could also add a fourth uncertainty: where the Allies would actually invade, more specifically, would it be at the easiest-to-reach crossing, at the Pas de Calais, or the technically more difficult Normandy? The Germans had hardened the Pas de Calais and concentrated a sizable amount of their reserves for a counterattack. But Normandy had terrible tides and steep cliffs. Where would Operation Overlord attack?

Looming over decisions were two additional Russian concerns. First, Stalin wanted an Allied invasion of Western Europe sooner rather than later, to create a second front and take some of the pressure off his troops. He pushed for this at a three-party (Churchill, FDR, and Stalin) conference in Tehran. Second, he insisted that the Allies resolve the issue they had put off—Morgan had already been named “Chief of Staff” to the Supreme Allied Commander. But who exactly was the Supreme Allied Commander?

This was a touchy point, not merely because it involved Anglo-American relations at the highest level, but also because several Generals had serious egos and thought adding “Supreme Allied Commander” to their resumes would have a nice look. Stalin had hit on something critical—Overlord would be an orphan without a strong-minded individual to take responsibility for it, to command resources of men and materiel, and to be personally invested in the plan’s success.

Enter Eisenhower. In some respects, he was an interesting choice. He had been turned down for a posting in Europe during WWI, and, before America entered World War II, he’d never had a command bigger than 800 men. He was, however, an extremely able man: a skilled administrator who worked well with his British counterparts, was deft in negotiating the minefield of others’ ambitions, and had a strong relationship with Marshall, the man at the top. Marshall had helped advance Ike’s career at several points, and, by the way, was himself a leading candidate for Supreme Allied Commander.

A lot of inside baseball went into Eisenhower’s selection—rivalries that had to be navigated, the self-esteem of Churchill, and the plausibly legitimate concerns of the British that an American might favor his own “side” in attention, acceptance of strategy, and allocation of resources. There was also the serious matter of whether the choice should be the enormously respected Marshall, who had been appointed Army Chief of Staff the very day the Germans invaded Poland to ignite World War II. Marshall was, quite literally, the top American General; he had served with great distinction and really was, in the words of military historian Forrest C. Pogue, the “Organizer of Victory.” Yet the British were less than enthusiastic about Marshall, and FDR needed him in Washington. Marshall was too dignified a man, with too great a sense of duty, to make it difficult for FDR by asking, so Roosevelt, who occasionally mixed dignity with a bit of guile, made it difficult for Marshall by refusing to insist. It would be Ike.

We are fortunate to be able to hear Ike speak for himself about the role he was given. This month, we commemorated the 80th anniversary of D-Day at Normandy. It was, as these events are, carefully staged down to the footsteps and camera angles, with high-minded speeches from world leaders (including President Biden). This year’s celebration had an additional element of sadness. About 200 surviving troops were able to make the trip and tell their stories, many stalwarts of the Greatest Generation, and all in attendance must have known that the next five-year celebration will have fewer. Some of those men, or their brothers in arms, might have been in attendance 60 years ago, at the 20th Anniversary, when Walter Cronkite, together with Eisenhower, filmed the CBS News Special Report D-Day Plus 20 Years: Eisenhower Returns to Normandy.

You can find it here, where the 74-year-old “Most Admired Man In America” walked the Normandy beaches with the “Most Trusted Man In America,” retracing steps and rekindling memories.

A bit of a head’s up. Be patient with it. This is grainy, filmed in black and white, with uneven sound quality at points, particularly when the filming was done outdoors. There is some historical footage, but most of it, to my eye the most compelling, is Eisenhower moving about from place to place, sometimes in a jeep, more often walking, explaining, describing. Cronkite is a perfect foil—he realizes it’s Ike and Normandy that the viewer is there for. He never competes for airtime. The decision to call Ike “General Eisenhower” instead of “President Eisenhower” is the right one. It reminds you that this old man was the leader of the more than 150,000 troops, 5,000 ships, and 11,000 aircraft that took part in the initial invasion. Within a week, the beaches were secured and over 326,000 troops, 50,000 vehicles and 100,000 tons of equipment had landed at Normandy. That number grew to 850,000 men and 150,000 vehicles. By the end of August 1944, the Allies had reached the Seine, liberated Paris, and uprooted the Germans from northwestern France, effectively concluding the Battle of Normandy. The stupendous, sustained team effort made D-Day a smashing success.

Ike begins with a short explanation of how it all came together—the planning work of General Morgan, the special training given the troops, how Normandy (instead of the closer, less technically difficult Pas de Calais) was chosen as the spot, and how weather (as predicted by Britain’s Group Captain James Stagg) played a critical role. To land successfully at Normandy, you had to thread a needle—in Ike’s words, “time, tides, and the moon.” With tides up to 22 feet and other physical challenges, only a few days each month could be suitable. D-Day had been planned for June 5th, but Stagg convinced Ike the weather could cause a catastrophe (Stagg was right—a huge storm hit that day). This was tremendously deflating—would they have to wait another month? But Stagg also told Ike that June 6th would open a narrow window, perhaps 36 hours, in which the landing could be launched. Ike pondered it. Would he tell the men in the ships who had been sitting around, crammed like sardines, many seasick, that they’d be on their way?

Ike had a fine staff around him, but the final call was his. About 4:15 p.m. on June 5th, he gave the go-ahead. After writing his Order of the Day, he penned a secret second one, taking all the blame for the failure his leadership had caused.

He must have known what a tremendous gamble he was taking—even with the passage of 80 years, it still hard to grapple with it. The projected casualty rates for the first waves of men on the beaches was astronomically high, and, even if they could secure the beaches, no one knew how the Germans would respond and how fierce would be the counterattacks.

Omaha Beach is where some of those fears played out. There’s a bit of archival footage showing the chaos, dead bodies, overcrowded landing ships lurching and flipping. Then the men disembark into the chest-high waters, many of them seasick, holding their rifles above their heads, and you almost have to take your eyes off the screen. The Germans may not have fully reinforced, but they were ready to hail down death on the unfortunates who staggered toward the beach. Many huddled behind sandbanks, paralyzed as the tides came up behind them, choosing between being shot or drowning.

Then, a small miracle—one, I think, Ike must have kept in his mind all those years.

They were under fire all the time, and finally some hardy soul just got up and said: Come on fellows, I’m sick of this and let’s try it, and we began to see these little individual acts of heroism, leadership coming to its very acme, you know, and a fellow starts off for that ground up there, and gets two or three behind him, and they become 20 or 30, and finally you’ve got some real power and things begin to lessen up.

This part, right here, I think is telling. All that planning by the officers, the experts. The finest military equipment that could be made. A massive misinformation infrastructure to distract the Germans. Heroics by outfits like the tough 101st Airborne Division’s battle-tested, genuinely high-quality leadership. Luck that the Germans didn’t catch onto the deceptions, didn’t relocate their reserve Panzer groups after the initial landings. Every bit of it essential, but none more than the simple acts of the average soldier who might have been too scared to stay put, and so joined his fellow Americans and went forward. On Omaha beach, they had answered every question.

The documentary closes with Ike seated at a bench in the American cemetery at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, which overlooks Omaha Beach. Speaking of the 9,000 who were buried there:

These men stormed these beaches, for one purpose only, not to gain anything for ourselves, not to fulfill any ambitions that America had for conquest, but just to preserve freedom, systems of self-government in the world. Many thousands have died for ideals such as these…. Now every time I come back to these beaches or any day I think about a day 20 years ago, I say once more, we must find some way to work to peace, and really to gain an eternal peace for this world.