by Rafaël Newman

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.

It was my birthday last month, a “round” one, as anniversaries ending in zero are known in Switzerland; and in gratitude for having made it to a veritably Sumerian age, as well as for the good health and happiness I am currently enjoying, I threw a large party for family and friends. Then, not quite one week later, I flew off to Albania, a land I have come to associate with the sensation and enactment of gratitude.

Albanians in official capacity are fond of giving each other elaborately worded certificates of gratitude, presented in velveteen dossiers at formal ceremonies. I know this because I have attended several of these ceremonies. I have even received such a certificate myself—for, although not a native of Shqipëria, I have now twice been invited to participate in Albanian cultural affairs.

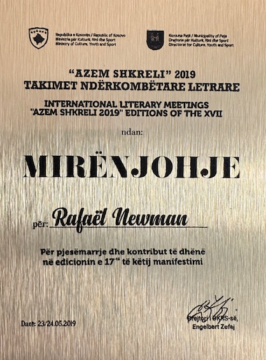

The first occasion, in 2019, was a literary festival in Pejë, in northwest Kosovo, where I joined a host of poets from across the Balkan region and beyond to read poetry in memory of Azem Shkreli (1938-1997), a local man of letters. During the closing ceremony, surrounded on the stage of Pejë’s municipal theater by the many poets in attendance and congratulated by various Kosovar dignitaries, I was handed my certificate by the woman who had invited me to the festival, my friend Entela Kasi, president of the Albanian PEN Centre.

The certificate—in fact, a metallic plaque affixed to a plush red display case—is engraved with the words MIRËNJOHJE për Rafaël Newman për pjesëmarrje dhe kontribut të dhënë në edicionin e 17 të këtij manifestimi: “GRATITUDE to Rafaël Newman for his participation and contribution to the 17th edition of this event.” Well, the gratitude was mutual: I had been treated to readings, music, and banquets, and had been afforded several public venues to present my own work, including a poem, written in Istanbul, which Entela had translated into Albanian for the occasion.

I had met Entela some years before, in North Macedonia, when as a member of the Swiss-German PEN Centre I took part in an International PEN conference on minority languages held on Lake Ohrid, on the Albanian border. And now, this past month, from May 24 to 28, five years after that encounter in Pejë, Entela had invited me once again. It was my first ever excursion to the country of Albania, rather than to Kosovo or the “diaspora” around Skopje, one of the strongholds of Skanderbeg, medieval Albania’s venerated protector against the Ottoman occupiers. And it was my second opportunity to participate in an Albanian cultural event.

That event, Netët Korçare të Poesizë, or “Korçë Nights of Poetry,” is a literary festival that takes place annually in the town of Korçë, in the southeast corner of Albania between its borders with North Macedonia and Greece. Entela had organized the Nights of Poetry this year, together with Jorida Tollkuci, director of Korçë’s public library, and had asked me to serve on the jury.

We were to judge entries by the poets invited to participate, from various Balkan countries (Albania, Kosovo, Romania, Slovenia) as well as farther afield, from Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Switzerland, and Turkey. We heard from the entrants, in their native tongues and in Albanian versions read by students from the local conservatory, on the glassed-in terrace of a local hotel; at the splendid National Museum of Medieval Art on the outskirts of town, among red and gold religious artifacts preserved from Enver Hoxha’s iconoclasm; and at a gala finale, complete with folk dances and singing, in the nearby municipality of Devoll.

Earlier that weekend we had been granted an audience by the mayor of Devoll at the county seat, where Entela had presented him with his own black velveteen dossier containing a certificate of our gratitude. Now, when the time came to announce the winners of the festival competition—Mariana Gorczyca of Romania, Güney Özkılınç of Turkey, Liridon Mulaj and Besnik Mustafaj of Albania, and Barbara Pogačnik of Slovenia—I stood on stage at the MIK Hotel with Entela and Ernestina Halili, the third member of the jury, this time as a presenter, not as an honoree. It was my duty to hand his award to Besnik Mustafaj, a charming novelist and diplomat with whom I conversed in French (he had been Albania’s ambassador in Paris and had served as the country’s Foreign Minister from 2005 to 2007) while he chain-smoked hand-rolled cigarettes throughout the event.

Besnik’s award—his certificate of gratitude—was mounted in a red display case identical to the one I had received in Pejë. And when I returned home to Zurich, I took mine down from the bookshelf and had another look at it; and I was reminded of something that had struck me in 2019, when I was first immersed in the Albanian world, and which had now taken on a new significance.

The Albanian language, although a member of the Indo-European family, is a so-called “isolate,” the only remaining member of the Albanoid branch of the Paleo-Balkan language group: which means that it has no near living relatives. It is the official language of Albania and Kosovo and has shared official or recognized minority language status in various other Balkan countries and in Italy, where there is a long-established diaspora community. (This community extends through Greece, where the sizable presence of its speakers sometimes occasions controversy, into Europe and beyond the oceans, both Atlantic and Pacific, into the Anglophone world.) Albanian grammar, although idiosyncratic in its treatment of such features as mood and negation, is similar to that of other highly inflected languages, and its distant kinship with the tongues of the surrounding peoples, particularly the Greeks, is displayed in cognates as well as in loan words.

The Albanian language, although a member of the Indo-European family, is a so-called “isolate,” the only remaining member of the Albanoid branch of the Paleo-Balkan language group: which means that it has no near living relatives. It is the official language of Albania and Kosovo and has shared official or recognized minority language status in various other Balkan countries and in Italy, where there is a long-established diaspora community. (This community extends through Greece, where the sizable presence of its speakers sometimes occasions controversy, into Europe and beyond the oceans, both Atlantic and Pacific, into the Anglophone world.) Albanian grammar, although idiosyncratic in its treatment of such features as mood and negation, is similar to that of other highly inflected languages, and its distant kinship with the tongues of the surrounding peoples, particularly the Greeks, is displayed in cognates as well as in loan words.

What caught my attention, however, in Albania last month as it had five years ago in Kosovo, was not Albanian grammar but orthography: or rather, one peculiarity of Albanian’s use of letters to represent its phonetics. Since its debut as a written language, in the 15th century, Albanian has been set down in a variety of ways, using a range of local or more distant alphabets (Roman, Greek, Cyrillic, Arabic). In the early 20th century, finally, Albanian orthography was standardized, using the Latin alphabet enriched with various consonant clusters or “digraphs” (th, nj, rr), as well as two letters bearing special diacritical marks: ⟨ç⟩, a c with a cedilla, to represent a voiceless palato-alveolar sibilant affricate, or a sound like the “ch” in “chip”—and ⟨ë⟩, an e with two dots over it, to represent the mid central vowel known as a schwa [ə], a “reduced” sound, as in the second e of the English word “letter”.

Albanian and Luxembourgish are evidently the only European languages to use the ⟨ë⟩ to represent the schwa. And it was this eccentric character, the Albanian e with two dots over it, that fairly jumped off my plaque when I received it, in Pejë in May 2019: mainly because it appeared in the central word “GRATITUDE” (MIRËNJOHJE) set directly above my first name, “Rafaël”, which also contains the character—to wit, an ⟨ë⟩: an e with two dots over it.

Albanian and Luxembourgish are evidently the only European languages to use the ⟨ë⟩ to represent the schwa. And it was this eccentric character, the Albanian e with two dots over it, that fairly jumped off my plaque when I received it, in Pejë in May 2019: mainly because it appeared in the central word “GRATITUDE” (MIRËNJOHJE) set directly above my first name, “Rafaël”, which also contains the character—to wit, an ⟨ë⟩: an e with two dots over it.

The two dots placed over the e in my first name, however, serve a different purpose than do those in the Albanian ⟨ë⟩. My two dots are a diacritical mark known as a diaeresis and are placed over a letter (invariably an e or an i) in a sequence of two vowels to indicate that they are not to be pronounced together, in a diphthong—as in “Caesar”—but rather as two separate sounds—as in “Rafaël”. The diaeresis is not the same as an umlaut (which is never used over an e or an i), although that German term is sometimes used by assimilation to refer to the diaeresis, perhaps because it is better known, or easier to pronounce. (As it happens, during my first visit to the Albanian world, in Kosovo in 2019, one of the poems I read at a public event, followed by Entela’s Albanian translation, contained a reference to the actual umlauts I had seen on a trip to Istanbul—to “the colour-coded umlauts” of the vowel-harmonizing Turkish language: so I had perhaps been influenced myself, in my choice of text to present, by the same erroneous assimilation.)

But the diacritical mark in my first name is more than simply a phonetic signifier: it is also the vestige of a personal archeology, one whose deepest fundament is an early celebration of my birthday.

When I was six years old, my mother gave birth to her third child: a girl, my sister Zoë. In fact, when Zoë was born, in early June 1970, I had not been six years old for long, having had my birthday just three weeks earlier, in mid-May. And that birthday, which was celebrated in the penumbra of my sister’s birth, and thus at risk for being overshadowed by that looming event, was marked by a more immediate, signal intrusion of its own.

Despite the late stage of her pregnancy, my mother had managed to bake me a large cake in the shape of a fire engine, among the fetishes of my boyhood, and had agreed to hold the party outside, near our apartment, at Westmount Park—although the weather, as is typical of Montreal in the springtime, was not particularly balmy. While she readied our picnic, which involved setting out the cake and other food on a blanket under a large tree, I led my guests in a loud game of tag. We returned to the tree precipitously when we heard my mother shouting: a neighborhood dog had taken advantage of her momentary inattention, had managed to devour much of the cake, and was now galloping away. We took up chase, incensed. We followed the dog all the way to the house we saw it disappearing into, one of the elegant brick buildings surrounding the park. We rang the doorbell, explained the offense to the woman who answered the door, demanded that she release the culprit into our mob-justice hands—and were told, to our chagrin and schadenfreude, that her pet, having just excreted my birthday cake all over her Persian rug, was currently cowering in the bathroom.

So when my sister was born, barely three weeks later, I was still in the mood to reclaim what had been stolen from me, to claw back my proffered and purloined dessert(s). But I did this in a roundabout fashion. At some point earlier during our mother’s pregnancy, our father had asked my younger brother and me whether we would like to suggest names for our future sibling. If she happened to be a girl, I had said airily, I would like her name to be Sophie; Adam, just four years old and with less high-flown pretentions (or perhaps greater ambivalence) had insouciantly proposed Crummy Bush.

In the event, the baby brought home from the hospital had already received the name Zoë, a choice about which we had not been apprised and which had no particular resonance for us (it was likely inspired by the actress Zoe Caldwell and by J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, neither of which belonged to our childish cultural landscape). And when I saw, with my burgeoning literacy, that her name was to be spelled with two dots over its second vowel, presumably to prevent its mistaken pronunciation to rhyme with doe, I decided that I needed to festoon my own signifier with a similar mark.

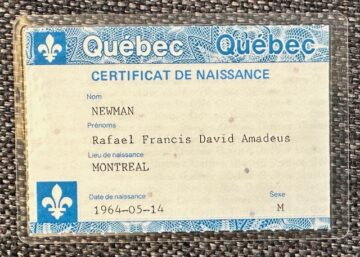

Because my parents had not, in fact, wanted (or needed) my name to bear a diaeresis. It is often written without one (as is Zoë, in fact, which didn’t make it any easier for me). My Quebec birth certificate, which I had been obliged to have reissued, in the process of renewing my Canadian passport in 2002, after the 9/11 hijackers had used forged certificates like mine to enter the US from Canada, still stolidly shows my name with an apparent diphthong, rather than with my chosen diaeresis: Rafael.

Because my parents had not, in fact, wanted (or needed) my name to bear a diaeresis. It is often written without one (as is Zoë, in fact, which didn’t make it any easier for me). My Quebec birth certificate, which I had been obliged to have reissued, in the process of renewing my Canadian passport in 2002, after the 9/11 hijackers had used forged certificates like mine to enter the US from Canada, still stolidly shows my name with an apparent diphthong, rather than with my chosen diaeresis: Rafael.

The two dots over my first name are thus a mark of my own will to distinguish myself, an early attempt at self-fashioning, an inchoate nom de plume: but they are also the trace of the ressentiment I bore against a world that had deprived me—of recognition for my nomothetic chops; of my special status as the elder of two sons, now challenged by the presence of a unique female sibling; and, perhaps most urgently, of birthday cake. (A further effect of that fateful al fresco encounter is a lifelong suspicion of dogs.)

When I now saw the Albanian ⟨ë⟩ juxtaposed with my own ⟨ë⟩, and realized that the purpose of the former was diametrically opposed to that of the latter—that the schwa represents a reduction of the vowel sound: indeed, in some cases, its elision entirely, while the diaeresis serves to uphold it, to ensure its distinct pronunciation—I was returned to my childhood, and to that early episode of my own anxiety about being overshadowed, and to its resolution with the stroke (or two) of a pen.

As it happens, in our subsequent history together, my sister and I have indeed been pursued by this very peril—that one of us might, or could, or did in fact overshadow the other. For the most part, however, despite my childhood fear, the peril has come from the other quarter: Zoë has at times endured psychological jeopardy emanating from me, from my extroversion and exhibitionism. I have been too loud, too libidinous, too loutish; too allied with our difficult father (and stepfather); and, most grievously, it has been all too easy for me to get and hold the attention of our mother, who was delighted by the antics of her pubescent sons and was always ready to laugh hilariously at our rude jokes, which were increasingly deemed inappropriate by a young woman coming to political consciousness in the 1980s and 90s.

Zoë surely felt more than simply overshadowed, by our performative masculinity and what must have seemed our mother’s Quisling support for a mini-system of dominance: she likely saw herself reduced to the status of a schwa, rather than distinguished, as she should have been, by her own diaeresis.

*

The festival in Albania, meanwhile, was splendid. It was a treat to spend several days in the company of fellow poets, to relish what Salman Rushdie has (perhaps condescendingly) identified as the special sodality enjoyed by writers of poetry, a camaraderie denied to novelists in their saturnine singularity. I saw old friends, like Vlora Ademi, who organizes a literary festival in Prishtina, and met new ones, including Lucilla Trapazzo, a Zurich-based artist and performer, Billy Ramsell of Cork, who declaimed his poetry, bard-like, from memory, and Anna Lattanzi, who writes about Albanian culture from her home in Italy. I encountered members of a new generation of Albanian poets, among them Antonio Babliku, my own minority preference for an award. We trudged up a hillside in Hoçisht to visit the home of Marigo Posio, the “mother of the flag,” the woman who is reputed to have sewn the first eagle-emblazoned crimson ensign of a newly independent Albania in 1912.

Throughout the weekend, however, I was also confronted with what I had seen in that juxtaposition of words Albanian and English: that what seemed like the very same diacritical mark could, given a change of linguistic context, mean two very different things. That it might be possible to compress two entirely opposed meanings into one single signifier. That what appears to be a schwa—a reduced version of an otherwise prominently pronounced vowel—might in fact be a diaeresis, that same vowel’s exaltation on a little pedestal of breath. Or vice versa. That what seem to be identical twins, or at least closely related, physically similar cognates from the same family, might have entirely different ways of being in the world, their “natural” kinship shaped differently by divergent experiences of nurture.

And I learned something else in Albania: an enigmatic oddity of linguistic history, something ultimately unassimilable to the personal psychohistory going on in subtext as I participated in the festival, but which felt nevertheless like a potential key to the way I had projected elements foreign to her onto my infant sister.

In an idiosyncratic development, the Albanian language, alone among its various distant relatives in the Indo-European family, has preserved in its kinship vocabulary an ancient, ambiguous form. Whereas other related languages use some variant of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root *méh₂tēr to refer to one’s maternal parent, an Albanian’s mother is known as nënë (as in Nënë Teresa, the country’s controversial, missionizing export), while an Albanian’s sister, reflecting the fact that the PIE form originally referred to one’s maternal aunt, is known as motër.

In other words—if you will—the mother I had likely been projecting onto my sister has been present in her name all these years, at least in the land of schwas dressed as diaereses; which is also, however, for me from now on, the land of a certain stylized gratitude.