by Mindy Clegg

The Cold War ended somewhere between 1989 and 1991 or if you take the disintegration of Yugoslavia into account, maybe into the 2000s. It is now seen as the end of an era, a closed loop in history. It started with the Communist revolution in 1917 and ended with the end of one-party communist rule in Eastern Europe. The dissolution of the Soviet Union especially signaled the end of the debate about the two supposedly opposing economic systems. The argument goes that communism as practiced in the second world proved unable to keep up with the productive capacity and flexibility of the western capitalist systems, which (many believed) were underpinned by truly democratic norms.

But what if it’s not the struggle between capitalism and communism that was really at the heart of the twentieth century, but was really a more expansive struggle within the world system that developed since the sixteenth century? What if we’re still in the midst of it? I argue that there was a deeper conflict rooted in the debate over who gets to decide how our societies function. This struggle reaches back to the past and shapes our present. We can see this deeper struggle within the communist-capitalist conflict, as that narrative allowed the US and the Soviet Union to double-down on various bad-faith actions with regards to either their own populations or their actions abroad. The fight is between democracy and authoritarianism, the people and the powerful. Democracy clashed with the authoritarian reactionary forces since before the age of revolutions, making the Cold War merely a part of a larger dialectical discourse of the modern world.

Beginning with the age of revolutions a phrase popularized by Eric Hobsbawm, kicked off by the American, French, and Haitian revolutions, we can see a shift in the history of political structures around the world. This was in part a byproduct of the developing capitalist economy unleashed by the brutal colonization of the Americas (and later the rest of the world) by Western Europeans. But we can see the struggle for greater freedom and democracy in the development of the Atlantic world during the eighteenth century. Historian Angela Sutton argued in her book that enslavement in North American came to look the way it did because of the British empire’s successful attempts to end pirate attacks on officially sanctioned slave ships. The British navy’s defeat of Black Bart off the west African coast in 1722 allowed the British to dominate the slave trade in the Atlantic. That meant their race-based interpretation of unfree labor became the norm for slavery in North America and later the United States. We still live with those consequences today, she correctly concluded.1 But this was also about labor on British ships, similar to how the development of the sugar trade in the Caribbean shaped labor in England, as Sidney Mintz argued.2 Pirate ships were often more diverse and even freer places compared to ships operating under official imperial flags. Joining one could be seen as “voting with one’s feet.” We should not gloss over the violent and bloody actions of pirates, but a level of democratic practice existed in comparison to imperial ships. Many men and some women found themselves willing to give up their sanctioned labor for the pirate life, despite the obvious risks. It is important to note that these pirates also often participated in the slave trade. Yet, plenty saw their defection to piracy in terms of labor, leaving a low-paid job full of abuse, to a place that offered some opportunity for building some personal wealth.

Another example of a grassroots attempt to assert the people’s rights happened during the Luddite uprisings in the early nineteenth century. That event calls the typical teleological interpretation of the development of the modern world into question, casting the emergence of the modern, technologically driven economy as one of a fight for greater rights for working people. New technologies are not always about freeing up workers, but often about freeing up profits by devaluing labor. In Brian Merchant’s book about the Luddite uprising, he drew parallels between then and the computing sector today. He noted how leaders in the tech industry seek to devalue labor via automation. In doing so, Merchant explicitly argued that both are not examples of technology improving our lives, but represent an ongoing struggle for greater democracy and labor rights.3 Although in modern parlance, being a Luddite means to irrational oppose technology, the actual Luddites had a very good reason to oppose the new technologies being adopted by the wealthy factor owners. The new means of mass-producing textiles were meant to replace their deeply skilled labor with unskilled workers (women and orphans, often) who could be underpaid and abused. The uprisings were a democratic movement aimed at preserving specific rights for workers. Much of the current labor struggles continue to mirror these uprisings of the early industrial economy, including in the tech sector. Many CEOs laud the rise of AI because they feel it can replace skilled, highly paid tech workers, a point often ignored in our discussions around these LLMs. Labor struggles around technology is an important historical thread to follow.

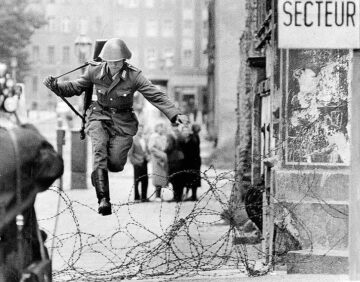

What about the communist world? Many argue that the Soviet Union represented a much more democratic worker-run state. There is truth to that when compared to the state it replaced, which was undoubtedly an authoritarian, theocratic monarchy. Workers did make up the rank and file, as well as the leadership of the Communist party. The third Soviet premier, the irascible Nikita Khrushchev for one rose through the ranks, as he was originally a metal worker. Many of the founders of the Soviet Union were from working class backgrounds. Lenin had freed serfs in his family lineage and Stalin was the child of a working class people in Georgia. It is also true that many working class people, both from the early industrial sector and from the much larger agricultural sector in Russia, not to mention soldiers, embraced the revolution and supported its ideals. Certainly, the vast development undertaken by the government under Stalin transformed the country in a handful of years, raising millions out of abject poverty. This likely explains that, despite the harshness and human rights abuses associated with Stalin years, he still had some genuine support among the Soviet people. We should question just how democratic life was in the Soviet Union by a variety of metrics. The Soviet dominated eastern bloc were one-party states, so what many consider democratic practices were obviously missing. But were there other forms of democratic practices evident? Some historians have argued in the affirmative. One example was from historian Donna Harsh, whose work examined women’s engagement with the state in East Germany. East German women found ways to make their views known and to shape party policy, despite the lack of party politics.4 Despite the lack of parliamentary politics, people found ways to practice democracy. However, the state could and did often push back against that democratic impulse, such as with Solidarity in Poland founded as a labor movement in 1980. Built on labor activism, the union gained millions of members quite quickly. Then the Polish government cracked down hard, but eventually the movement democratized the Polish state along more traditional parliamentary democracy lines. In both cases, we can see democratic impulses within these states imagined to be purely authoritarian, and how the state would either accommodate or crack down on those impulses.

This was true in the supposedly more democratic west, too, a push-pull between democratic impulses and elites using the state to retain their privileges. The long history of the Black freedom struggle in America more than illustrates the point there. The attempt to keep millions of Black Americans enslaved and then the imposition of second class citizenship after the Civil War was just that: an attempt to ensure that some retained greater rights than others. Black Americans fought for centuries to gain those rights, often met with violence from the state. Often, we think of that struggle as very liberal struggle. However, during the interwar period the Civil Rights movement had a much more radical edge, including an embrace of socialism and the Soviet Union.5 The movement for Black rights, whatever politics activists embraced, was essentially a democratic movement, in the broadest sense. It was true that the Soviets regularly employed whataboutism in their anti-American propaganda with regards to racial segregation, it was also true that the US was not a true democracy because of Jim Crow. Despite claiming the democratic moral high ground, the US failed by its own metrics. So did the Soviets.

In addition to the democratic failures at home, both sought to dominate the global economy and embraced destructive foreign policies. The war in Vietnam and the war in Afghanistan provides us some examples. The US backed an obviously unpopular set of leaders in South Vietnam rather than allow for a vote which might have brought the Communists into power democratically. The resulting decades of war not only created a generation of American veterans who struggled with their physical and mental health, it utterly destroyed large swaths of Vietnam and devestated the Vietnamese people. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 contributed to the destruction of that country. The CIA poured money into the opposition, who would eventually form into two distinct groups, the Taliban who just recently retook power there and Al-Qaeda, who carried out a series of deadly terrorist attacks over the years. Both countries contributed to a highly destructive war in Angola which did not end until 2002. Much of the Global South, in fact, became a violent battle ground during the Cold War, at the same time that many have argued was a long stretch of peace. That was true only if one looked at the Global North. Some historians, such as Odd Arne Westad, has pointed out how the Cold War struggle between the great powers destabilized the decolonizing world.6 In addition to having questionable democratic practices at home, both also undermined it abroad in order to further their particular interests. Some might claim that the choices made by both sides were necessary, because of the existential threat posed by the other. It seems clear that both had a variety of choices they could have made. During the Second World War, both the US and Soviets did make those different choices, in the face of the threat of fascism. However, after that war, they choose the path of anti-democratic actions, as it was likely seen as the easiest path. We still live with the consequences of those choices.

Ultimately, the Cold War came down a struggle between two massive, imperialist states that claimed the moral and democratic high ground, but both failed to live up to their stated ideals. But that was part of a longer history of thrashing out the divisions within the European Enlightenment. Much of the history of the twentieth century was about putting the competing ideals of that philosophical moment to the test. Recently, the language of the dark interwar years and the fascist threat has come roaring back to life. This is in part because the neoliberal economy creates economic deprivation. This allows authoritarians a way to thrive, by promising quick, easy answers to complicated problems. In a recent interview with El Pais, political scientist Steven Levitsky discussed the general anti-government mood of our current era. He puts figures like Trump in the same category as the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez. The specificity of the political language they employed hardly mattered, what they did or do is key. They harnessed anti-government sentiment for their own gain while seeking less democratic structures for their countries. Figures like Trump and Chavez pretend like the answer to our shared problems rested in a singular strong man. They pit groups against each other in order to distract from how they are actually part of the problem. They are both fundamentally anti-democratic. Which brings me back to my thesis, that the Cold War itself was something of a distraction. Not to say that the conflicts weren’t real, because those caught in the cross-fire will attest to just how real they were. But digging into the realities of life under both the capitalist west and communist east, neither lived up to the promises made. Racism, misogyny, anti-communism and other phobic responses to difference plagued western democracies and made them less than democratic. The communist east often fell victim to an unacknowledged class system that no one was allowed to acknowledge existed. Both sought to hold the moral, democratic space, and both failed all of us. But if we’re to actually improve the world, we must honestly analyze weaknesses in our systems, figure out ways to address them, and center people rather than markets or mythical “volks” that are merely excuses for hurting marginalized groups. True democracy is built on an informed electorate, not on force and division. We must reject the easy, authoritarian, anti-democratic path for solving our shared problems. Someone like Trump can’t “fix it” and has no interest in doing so. Only the people working together can do that.

Footnotes

1 Angela Sutton, Pirates of the Slave Trade: The Battle of Cape Lopez and the Birth of an American Institution, Essex, CN: Prometheus Books, 2023, see especially the last chapter 219-236.

2 Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

3 Brian Merchant, Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech, New York: Little Brown and Company, 2023.

4 Donna Harsch, Revenge of the Domestic: Women, the Family, and Communism in the German Democratic Republic, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

5 Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights 1919-1950, New York: WW Norton & Company, 2008.

6 Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times, Cambridge. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012.