by Jeroen van Baar

Now that I live in Washington DC, I take every opportunity I get to sample the seafood sold at a floating market down by the wharf. It’s the oldest open-air fish market in continuous operation in the United States, dating back to 1805. But while the market is a local feature, the fish itself is not. This is partly due to globalization: tilapia is farm-grown in countries like China and Indonesia, frozen, shipped, and sold defrosted at the wharf. But even the cod, a fish historically abundant in the Atlantic Ocean, is rarely caught nearby. As it turns out, the reason for this is not economical, it’s ecological. And it provides a valuable view into the weaknesses of science and mathematical modeling.

The story starts about five hundred years ago, when Spanish and Portuguese fishermen sailed West to find huge populations of Atlantic cod swimming around what we now call the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. The fishing was good and the fishermen hauled home barrel upon barrel of Basque-style salted bacalao, roughly 150 metric tons per year. This became a staple protein in Europe for centuries and for a while, all was well.

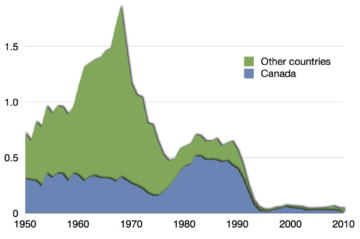

Enter modernity. By the middle of the twentieth century, engineers had developed such powerful bottom-scraping nets and fish-finding sonar systems that cod landings shot up to over 1,000,000 tons in 1968 (see figure). European freezer trawlers took home a big share of this pie, which upset local fishermen who had started seeing sub-par yields. The Canadian government therefore claimed an exclusive economic zone not 3 but 200 miles off the coast, which contained about 90% of the Grand Banks area. The locals then deployed massive trawlers of their own. This led to a decrease in overall cod landing but a recovery in Canadian cod production, and for a while, all was well.

Soon, however, the yearly yield of cod stagnated again. This is when fishermen and policymakers got worried. Could it be that there was something wrong with the cod population itself? Clever ecological modelers came up with a way of calculating a ‘maximum sustainable yield’ (MSY), set at 16% of the total population, which should theoretically leave enough fish to repopulate each year. For a while, all was well, as this mathematical might settled everyone’s nerves. But fishing floundered further and the Grand Banks cod population collapsed almost entirely in 1992. The government quickly called a moratorium on cod fishing, which was renewed indefinitely in 1993. It marked the end of what was once the greatest fishery on Earth. Read more »

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

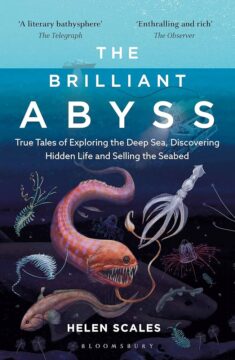

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024 In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.