by Carol A Westbrook

I first recognized discrimination against women while I was in the 1st grade. I attended a Catholic school run by nuns, the Sisters of the Holy Family. When Sister asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I answered, “A Priest!”

It made sense to me. I could see myself in a leadership role in the Church. In the Church, priests have the most power and maintain dominance over all the congregation, and that’s where I wanted to be!

“Why Carol,” Sister said to me, “you must know no girls are allowed to be priests. But you could be a nun.”

A nun? No way! Nuns were clearly subservient to priests, and did all the inferior work in the parish. They cleaned, cooked, ran the school. They had no power. No thanks, not for me. I couldn’t understand why women can’t be priests. If not a priest, I didn’t want a religious career.

By the time I was 9, I realized it was not just the Church—it was jobs, and banks, and sports, and education, and even my own family. I was pitcher in my brother’s sandlot baseball team (actually, our “whiffleball” team in the alley). At age nine, my brother made me leave the team, even though I was a good pitcher.

“No girls allowed” he said. Clearly, anything interesting, exciting or important was for boys only. No girls allowed. It wasn’t fair—and having grown up with 3 siblings, vying for the largest piece of cake, I was very aware of the concept of fairness.

“No girls allowed” he said. Clearly, anything interesting, exciting or important was for boys only. No girls allowed. It wasn’t fair—and having grown up with 3 siblings, vying for the largest piece of cake, I was very aware of the concept of fairness.

I believed strongly that women did not have to be nuns or nurses or housekeepers. Unless they wanted to. They could be anything they wanted, and I intended to make sure that was the case.

By the time I was in college, many women felt the same way that I did. We deserved equality, with our own Constitutional amendment prohibiting discrimination, just as the Civil Rights Bill protected people of color. When the Civil Rights bill, was ratified in 1964, it seemed likely that the ERA (Equal Rights for Amendment for Women) would follow soon thereafter. But there were (and are) many lawmakers who feel that women were the weaker sex, that they deserve special protections that the ERA would otherwise sweep away—e.g. protection from military draft, mandatory alimony, etc. In other words, women were NOT equal.

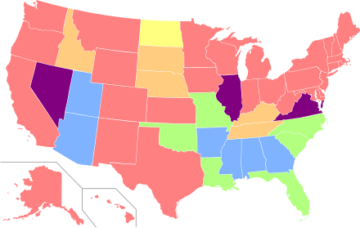

pink: : Ratified

Purple: Ratified after June 30, 1982

Orange: Ratified, then revoked

Yellow: Ratified, then revoked after June 30, 1982

Green Not ratified (approved in 1 house of legislature)

Blue Not ratified

To this day, the ERA has not been ratified by all the states (see the diagram) and therefore has not been accepted as a constitutional amendment, although most of the ratifying states accept it as law.

In the 70’s and 80’s we saw women succeed in new positions. In 1980 we saw the first class of women graduates from West Point; we now see female admirals and generals in the military ranks. There are women lawyers and race car drivers and astronauts. And as far as I was concerned, women could take any profession they wanted, and I wanted to be a doctor. I had the grades and the references and the test scores, and I was accepted by the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine.

If you look back over the class pictures in the hallways of Pritzker, you will see that each class had several women physicians – especially during the war years (1941-45). But it was almost certainly the case that these doctors were unmarried; as a woman you could be either a doctor or a wife, but not both. Never mind that a man could be a doctor and married and have 4 or 5 children; that pathway wasn’t open to women–not until I and my fellow boomers got there, that is! I think we knew that we were setting the precedents for future generations of women to become doctors and still keep our humanity.

In fact, being married and in med school was no more challenging that being married and in college; it required a lot of study time and commitment, but it was possible. It would be more difficult during the residency years when we had to put in long hours and overnights, but in those days the husbands were expected to pull their weight in housekeeping and cooking—and they did! I and my husband were both in medical school and we managed just fine.

A few years ago I attended a med school reunion, which included a panel discussion about the challenges women faced in med school. One of these was logistics: in many ways Pritzker was not ready for women. The loudest complaint was that there was no locker room for women students; men shared the surgeons’ locker room (where were the women surgeons? Answer: there weren’t any). Women students had to use the nurses’ locker room, which did not have green surgical scrubs—only pink nurses’ dresses. We demanded to use the surgeon’s (former men’s) locker room. Call rooms for women were not yet available, nor were safe night-time parking spots near the hospital entrance. Personal interactions were also a problem, as nurses were not quite sure how to treat female doctors and med students. I was aware that there was a deferential, flirtatious interaction between the nurses and male students and physicians, but I was not sure how I fit in. It took time and patience to work this out.

The most stressful time was yet to come: children! Only a few decades before I went to med school, in the 50’s and 60s, most families with children had stay-at-home-moms. That was not an option for the medical resident. The best years for child rearing are also the most productive of your career, so there is never an optimal time to have children. For me there was no choice; the IUD failed and I was 4 months along before I knew it! Needless to say, I was the first medical resident at University of Chicago to ever have children.

And I’m so glad that I did have my first child then; it broke the ice for having the rest of my three children. But there was no precedent for how to handle this in a residency. I took a month elective and 2 weeks vacation (total of 6 weeks leave) but I went back to work after 4 ½ weeks; I wanted to get credit for the residency year, and frankly I was bored sitting home with a child with nothing professional to do and no support. Later residency programs provided more generous maternity leave and accommodations for more time off.

Still, the difficulty with managing with a baby was not one of money; it was lack of resources. Babycare for young babies was almost impossible to find; and childcare for toddlers who were not yet toilet-trained was almost nonexistent! There were needs for housekeeping, shopping and cooking for me and my husband. It was a stressful situation that required more than money. Every family makes its own accommodations, however, and we found a loving, caring wife of a divinity student to take care of the baby, and my husband put in the extra effort to shop and cook for us. By then he had opted out of residency and pursued a career as a post-doctoral science fellow. Looking back, these stresses help us to better understand what resources are necessary in order to manage a household and a family, and what the next generation will need.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.