by Adele A. Wilby

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

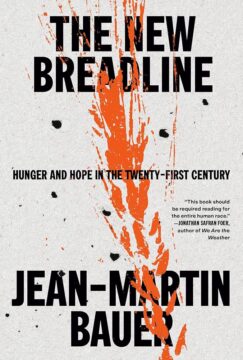

Jean-Martin Bauer’s book The New Breadline: Hunger and Hope in the 21st Century addresses those very issues of social oppression and politics also that create the condition of hunger for millions of people across the globe. He is well placed to author such a book. With twenty years of experience with the United Nations World Food Programme and now Country Director of the programme in Haiti, Bauer brings to the book a wealth of experience in humanitarian work to alleviate hunger in West Africa, Syria, Iraq and Central Africa, and now in his home country of Haiti.

Bauer tells us that fewer people than ever starve in the world today thanks to technological progress and the creation of systems to bring food aid to people. Indeed, at the turn of the 21st century the success in winning the battle against hunger was so encouraging the world’s governments publicly committed to eliminating hunger by 2030. That aspirational deadline however appears to have been kicked into the grass as tragically in 2023 it is estimated that 250 million people still faced acute hunger, double the number in 2020. Read more »

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019. I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”

I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”  There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.