by David J. Lobina

For someone who sees himself as a person of the Left, at least in the sense in which the political right and left were conceptualised by Norberto Bobbio ages ago – that is to say, as moral and political stances towards equality (and inequality) – and more concretely, as a sort-of anarchist, at least in the sense, this time, of being suspicious of authority, top-down impositions and ideas, and much preferring a society composed of spheres of self-realisation instead from the bottom up,[i] the advent and prominence of so-called ‘identity politics’ in recent years, especially in the English-speaking world, and most clearly, in the US, has been surprising, bewildering, and rather frustrating.

Even though identity politics is usually associated with the Left, both by friends and foes, I agree with some thinkers from the Left I actually follow, such as the academic Brian Leiter, that this kind of politics may well be ‘the narcissism of the aspiring bourgeoisie, who want to get their share of the “capitalist pie”, including their share of “respect” as reflected in language and culture’ – and likewise for the concept of equity so common and so often defended these days, which is not really a liberal principle per se, but more of a neoliberal keyword: no universal social programs to be set up, but instead we shall have micro-interventions here and there that can only produce a more ethnically diverse elite. Under these conditions, inequality and capitalism remain untouched, class politics unmentioned, the result a Left without the economics or the socialism, and on we go with elite representation and such worries (seriously, whatever happened to class politics?).

Rather surprisingly, at least to me, the obsession with such diversity concerns is ubiquitous here in the UK too, including at my daughter’s primary school in London, one of the most diverse cities in Europe. In June each year there is a so-called Diversity Week, which according to the Head Teacher is about ‘taking pride in who you are and all of the things that make you ‘you’, especially your differences’ (you can strike out the word especially from that statement), the main point to be conveyed being that ‘one opinion, lifestyle, religion, family make up, or cultural heritage is not more important than another; we are all individuals and our differences are what make us stronger as a community’.[ii]

As a case in point, the school once entered a local flower cart competition, and the chosen message on the cart was: We are all different, and that’s fine.

All of course laudable, at least at first sight. My point in this column is to push back a little bit, and to do so from the point of view of universality and commonality, which I regard as a much more significant property of human thought and belief systems – indeed, of human nature tour court. Or as the La Fontaine Academy flower cart could also have advertised at the competition: We are all the same, and that’s fine too! Read more »

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019.

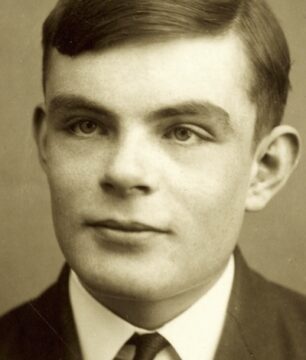

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019. I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”

I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”  There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

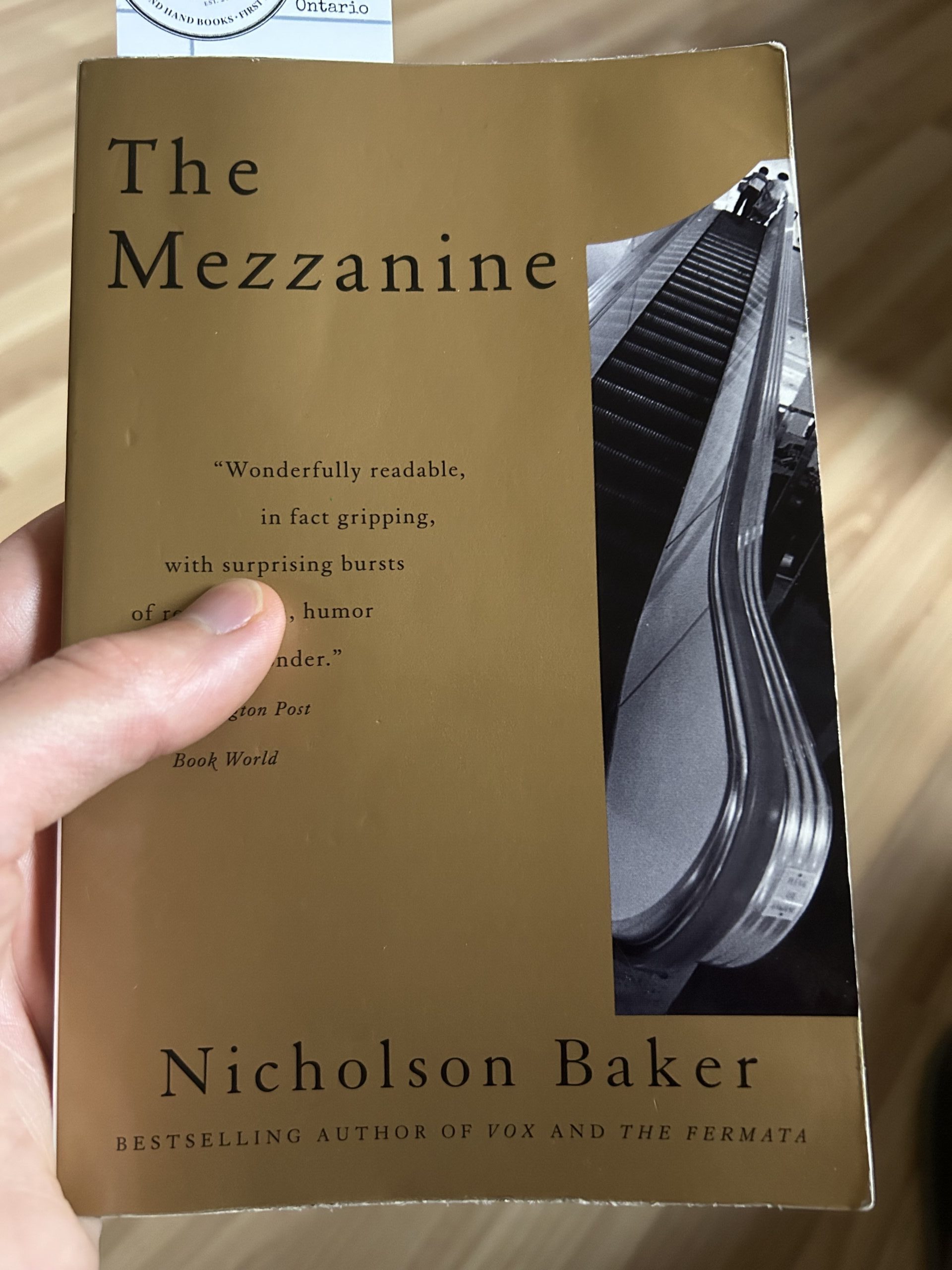

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.