by Olivier Del Fabbro

Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed that the “most ancient of all societies and the only natural one is that of the family.”[1] Similarly, Rousseau’s great antagonist, Thomas Hobbes, claims that “family is a small commonwealth.”[2] But what if the most natural and ancient of all societies is confronted with war? According to a survey by the International Rescue Committee, 74% of Ukrainians report being separated from a close family member because of the war.[3]

Maria (32) and Ivan (42) are such a family. Ivan was drafted in April 2022. Since then, he has been stationed in Donetsk, in the region of Kramatorsk. In the beginning, Maria and Ivan saw each other every four months for about ten days. Now, in 2024, he is allowed to come home twice a year for two weeks. “But you also have to count two days for travel.” The frontline is far away from where Maria lives, Chernivtsi, on the border to Romania.

On the 13th of April 2024, when Ivan came home for his two-week leave, Maria had just given birth to their daughter, Sophia, the previous day. Two weeks later, Ivan left heartbroken for the frontline. “I cried every day until the end of May,” Maria says. “Then, I realized that I must live for my daughter, for my husband. I did not want my husband to see me crying every day, because he was worried as well.” Maria and Ivan always planned on having a family, but Maria’s pregnancy was an accident. “I don’t regret it,” she says smiling at Sophia. “She is perfect.”

Maria grew up in Greece, with her Ukrainian mother and Greek father. She went to Chernivtsi to study medicine to become a dermatologist. In March 2024, shortly before Sophia was born, Maria’s mother came to visit and help her. But just as Ivan, she left at the end of April. Still today, she is waiting in Greece for her daughter, but Maria does not want to leave her husband. She wants Ivan to see his daughter.

“It’s very difficult to be a single mother. It’s just myself and my daughter.” Maria’s mother, her father, her brothers, are all in Greece. Ivan’s grandparents from Ukraine are long gone. His father has passed away, and his mother lives in Italy. “I am all alone.” Read more »

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on. A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

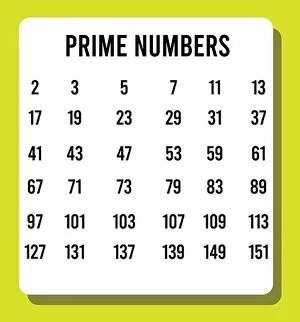

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

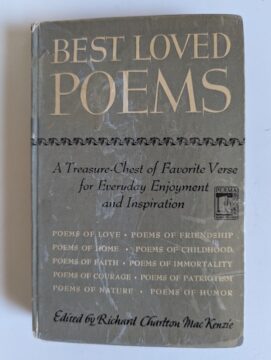

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.