by Jerry Cayford

On June 28 this year, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Chevron U.S.A v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1984). This was big, since that Chevron decision was the heart of the administrative state’s legal authority. Chevron formalized the executive civil service’s authority over complex decisions of practical governance, such as how to interpret and enforce tax law, ensure food safety, regulate trains and airlines, fund and oversee education, manage elections, and everything else we fight about nowadays. The nice view is that Chevron empowered expertise.

The cynical view (widely held) is that, through Chevron, a conservative Supreme Court gave the Reagan Administration power to ignore Congress’s laws by letting executive agencies twist their meaning at will; now, as those agencies have become more liberal and courts more conservative, a conservative Court has overturned Chevron in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), taking that same authority to twist the law’s meaning and transferring it from executive agencies onto courts. As Justice Elena Kagan says flat out, in her Loper Bright dissent, “The majority disdains restraint, and grasps for power.” I would not contradict the cynical view, on pain of appearing naïve. But I argue that there is a much bigger story here, one about how we as a society became threatened by authoritarianism and confused about truth.

That 1984 Chevron legal decision had an intriguing feature: it was considered, by its author Justice John Paul Stevens and his colleagues, to be nothing special, an uncontroversial repetition of common sense and long-standing precedent. How can that be? How could unanimous Supreme Court justices not know they were making history and remaking the law? We once wondered how the Earth could be spinning and circling the sun, yet we couldn’t feel the motion. The same puzzlement applies to the vast movements of history as to planetary movement: situated inside them, we don’t feel them directly; we have to figure out what is going on.

As Chevron evolved from its modest birth, it became a growing problem and its overturning an inevitability. There are familiar ways to tell this story (technocrats brought down by hubris; a pendulum swinging back to common sense), but a more illuminating, less familiar way situates it in intellectual history. The initial invisibility of Chevron’s Earth-shaking importance hints that Chevron shook the Earth by rejecting a century of intellectual development. Much more is going on than garden-variety power struggle. Read more »

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

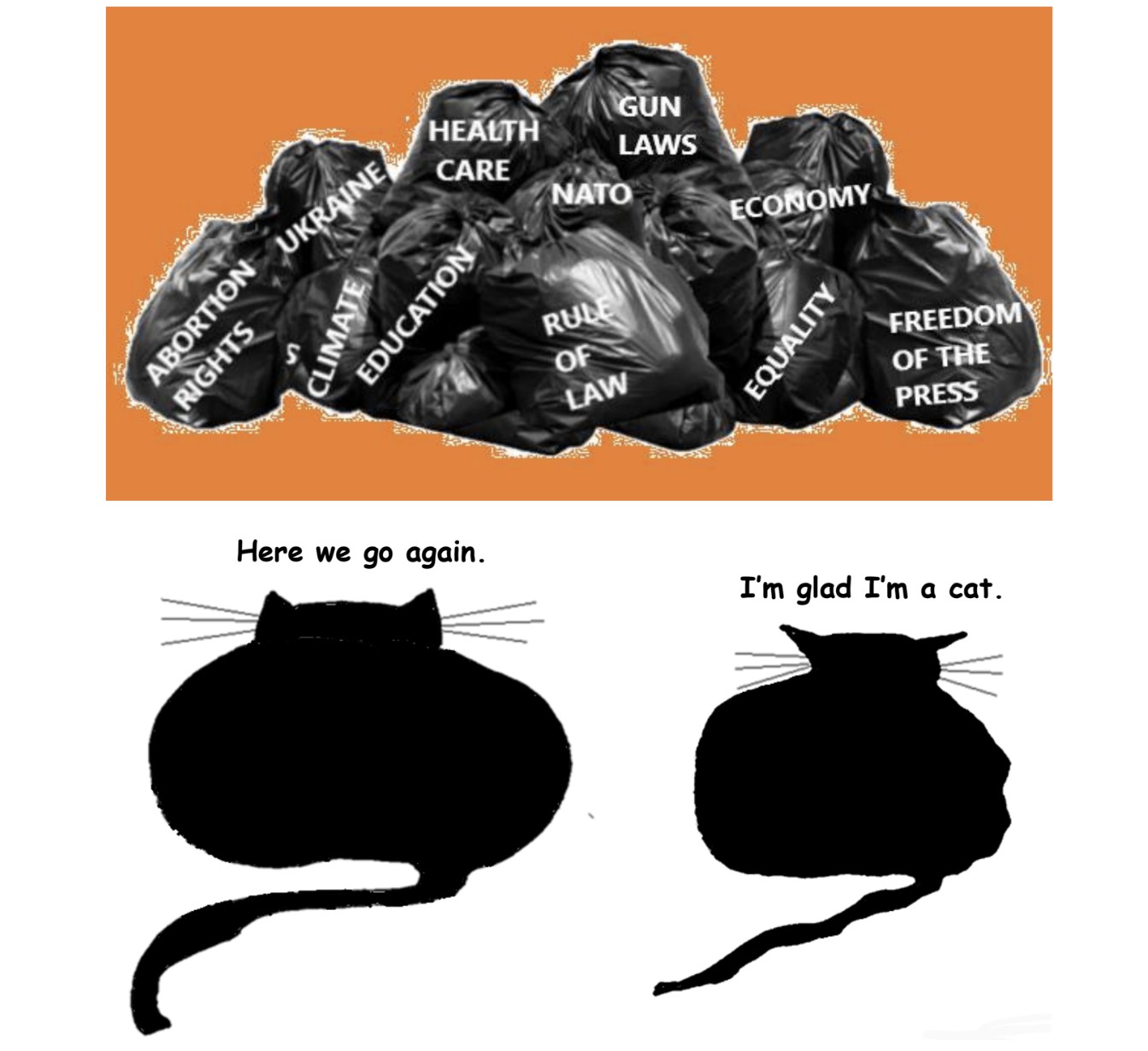

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.